The bowhead whale’s remarkable lifespan and low cancer risk stem from a finely tuned DNA repair system driven by a unique protein, CIRBP. Scientists found that this mechanism not only preserves the whale’s genome but can also…

Blog

-

Ceasefire at last: Pakistan and Afghanistan agree to truce after Istanbul peace talks; follow-up meeting set for Nov 6

Pakistan and Afghanistan finally agreed on Thursday to uphold a ceasefire during peace talks in Istanbul, according to Turkey, after the earlier discussions between the two sides had collapsed. The two countries had faced their most serious…

Continue Reading

-

Dying: A Memoir review – Benjamin Law’s adaptation of Cory Taylor’s book fails to satisfy | Australian theatre

Queensland-based author Cory Taylor published her memoir about the dying process as she was living it in 2016 – the same year American neurosurgeon Paul Kalanithi published his memoir about the dying process as he was living it, When Breath…

Continue Reading

-

Tokyo Inflation Quickens to Support Case for BOJ Rate Hike

Inflation in Tokyo rose at a faster pace, supporting the case for the Bank of Japan to keep raising interest rates gradually and giving the yen a boost.

Consumer prices excluding fresh food gained 2.8% in October from a year earlier in the capital, according to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications on Friday, with the main driver behind the acceleration being water charges. The median economist estimate in a Bloomberg survey was for a 2.6% increase after the gauge rose 2.5% in September.

Continue Reading

-

Candace Parker headlines star-studded 2026 women’s Basketball Hall of Fame Class

Three-time WNBA champion Candace Parker headlines the 2026 Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame class, which celebrates a powerhouse lineup of players, coaches, and pioneers who transformed the sport.

Announced on Thursday (30 October), the class…

Continue Reading

-

Florence + the Machine: Everybody Scream review – alt-rock survivor surveys her kingdom with swagger | Pop and rock

The title track of Everybody Scream provides a suitably striking opening for Florence + the Machine’s sixth album. A sinister organ and a choir of voices harmonise in the style of a horror theme, replaced in short order by the sound of…

Continue Reading

-

The macroeconomic implications of extreme weather events: Insights from advanced economies

Extreme weather events – such as catastrophic floods or prolonged heatwaves – are increasing in frequency and intensity (IPCC 2021). This has sharpened the focus of policymakers ahead of COP30 on the economic resilience of developing and advanced economies. While there is a growing consensus that these events cause serious macroeconomic losses (Krebel et al. 2025), accurately quantifying them remains difficult (Aerts et al. 2024).

For advanced economies, evidence of strong and significant negative effects has been more challenging to document, especially in studies using cross-country data (Botzen et al. 2019, Klomp and Valckx 2014). There is growing recognition that the highly localised nature of weather shocks calls for studying their impacts at a subnational level (Goujon et al. 2024, Dell et al. 2014), and that combining granular data across countries and event types is essential to fully capture their macroeconomic effects.

Against this background, in new work (Costa and Hooley 2025), we use regional data for over 1,600 regions across 31 OECD countries from 2000 to 2018 to assess the economic consequences of extreme weather events in advanced economies, including how impacts propagate beyond the original event location via spillovers.

Large, persistent, and non-linear impacts

The most severe events reduce GDP in a region directly affected by a disaster by up to 2.2% relative to trend, with losses of around 1.7% persisting after five years (Figure 1). But not all disasters matter equally. The most severe events – defined as affecting at least 0.1% of a region’s population – generate disproportionately larger output losses than more moderate disasters, while minor disasters show no measurable GDP impact. Such non-linearity has also been documented by others (Felbermayr and Gröschl 2014) and is likely due to capacity constraints – technical and organisational limits that bind only in big disasters (Hallegatte et al. 2007). Small shocks are absorbed; large ones overwhelm.

Figure 1 Change in the level of real GDP following severe disasters (percent)

Note: Lines show local projection estimates at each horizon after the disaster for all, moderate, and severe disasters; shaded bands are 90% confidence intervals.

Source: Costa and Hooley (2025); data: OECD, EM-DAT, GDIS (Rosvold and Buhaug 2021).Labour markets are a key adjustment channel: employment declines in line with GDP and affected regions see net outward migration. Mobility is an important coping mechanism for households, but it can also deepen local output losses by eroding demand and depleting human capital.

Severe disasters also put downward pressure on prices: the GDP deflator declines to about 1% below trend in the medium term. Demand shortfalls dominate any supply-side inflationary pressures from damaged capital, disrupted production and labour market dislocations.

These are net effects on output and prices, so they already incorporate offsetting forces such as reconstruction spending, insurance payouts, and government relief transfers. The persistence of large losses shows that such support, while helpful, is, on average, insufficient to return the economy to its pre-disaster path.

Negative spillovers to neighbouring regions

The economic damage does not stop at regional borders. We identify material negative spillovers: a severe disaster occurring within 100 km of a region leads to a further 0.5% decline in GDP – roughly a quarter of the direct effect. These spillover channels are likely to reflect several factors, including disrupted supply chains, reduced demand from nearby affected areas, and population displacement.

Combining direct and spillover effects and aggregating across OECD countries, severe disasters in our sample reduced GDP by over 0.3% per year on average, with spillovers contributing roughly half of the total loss (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Average annual impact of severe disasters on OECD GDP during 2006-2018 (percent)

Note: Panel A shows the average annual GDP loss across 31 OECD countries (2006–2018) from severe disasters, combining direct effects and spillovers from events within 100 km. Losses are derived by applying estimated elasticities over a five-year horizon and aggregating from region to country. Panel B plots the distribution of country yearly direct and spillover effects. The marker and horizontal line denote the mean and median, the top and bottom of the box denotes the interquartile range, and the whiskers denote the min and max values.

Source: Costa and Hooley (2025); data: OECD, EM-DAT, GDIS (Rosvold and Buhaug 2021).Why some regions are more resilient

The capacity of regions to withstand and recover from disasters varies significantly. Fiscal space matters: regions in countries with lower debt-to-GDP recover more quickly, as governments can deploy effective post-disaster support without requiring offsetting austerity measures that could exacerbate the economic downturn (Canova and Pappa 2021). Economic diversification and labour mobility also enhance resilience: diversified economies can shift activity to less-affected sectors, and higher mobility speeds up reallocation and limits persistent unemployment (Beyer and Smets 2015).

Sectoral patterns also differ sharply. Industrial output falls by more than twice as much as output in services after a severe disaster – unsurprising given industry’s reliance on fixed capital and networked supply chains – but it tends to rebound faster in the medium term as supply chains are restored and reconstruction spending ramps up.

Policy implications

Quantifying the potential economic losses caused by natural disasters is crucial for effective planning and decision-making. Our estimates – showing large, non-linear, and persistent costs even in advanced economies – call for climate damage projections to explicitly incorporate extreme-event impacts. The task is challenging, however, and while recent work has begun to incorporate temperature and precipitation volatility into climate damage functions, the most extreme ‘tail’ events are unlikely to be captured (Aerts et al. 2024).

The scale of losses also underscores the urgency of adaptation efforts in advanced economies, including investment in adaptive infrastructure – flood barriers, water storage, resilient transport and power – alongside credible post-disaster plans and deeper insurance markets (OECD 2024).

Our evidence of negative spillovers furthermore carries a clear policy message: climate adaptation cannot narrowly focus on the location of a potential hazard. When around half of the economic damage from natural disasters occurs in regions that are not directly hit, such a strategy would leave major costs unaddressed.

This points to several complementary priorities:

- Infrastructure resilience beyond the hazard zone. If supply chain disruptions drive negative economic spillovers, then resilient infrastructure investment needs to consider network effects.

- Cross-border coordination mechanisms. Effective disaster response requires shared early warning systems, joint disaster response and recovery plans, and potentially coordinated fiscal support.

- Reduce labour market frictions to reallocation. Promoting more flexible labour market institutions and targeted upskilling initiatives can help displaced workers transition more quickly into new employment in less-affected sectors, or regions.

Strengthening resilience to spillover effects – alongside broader adaptation efforts – is critical to cushion the economic and social impacts of extreme weather and to prevent disasters from widening regional inequalities.

References

Aerts, S, L Stracca and A Trzcinska (2024), “Measuring economic losses caused by climate change,” VoxEU.org, 2 October.

Beyer, R and F Smets (2015), “Labour market adjustments and migration in Europe and the United States: how different?”, Economic Policy 30(84): 643–682.

Botzen, W, O Deschenes and M Sanders (2019), “The Economic Impacts of Natural Disasters: A Review of Models and Empirical Studies”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy 13(2).

Canova, F and E Pappa (2021), “Costly Disasters & the Role of Fiscal Policy: Evidence from US States”, Fellowship Initiative Paper No 151, DG ECFIN, European Commission.

Costa, H and J Hooley (2025), “The macroeconomic implications of extreme weather events”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No 1837.

Costa, H et al. (2024), “The heat is on: Heat stress, productivity and adaptation among firms”, OECD Economics Department Working Paper No 1828.

Dell, M, B Jones and B Olken (2014), “What Do We Learn from the Weather? The New Climate-Economy Literature”, Journal of Economic Literature 52(3): 740–98.

Felbermayr, G and J Gröschl (2014), “Naturally negative: the growth effects of natural disasters”, Journal of Development Economics 111: 92–106.

Goujon, M, O Santoni and L Wagner (2024), “Global exposure to climate change at a subnational jurisdiction level”, World Development Sustainability 5, 100168.

Hallegatte, S, J Hourcade and P Dumas (2007), “Why economic dynamics matter in assessing climate change damages: Illustration on extreme events”, Ecological Economics 62(2): 330-340.

Hsiang, S and A Jina (2014), “The causal effect of environmental catastrophe on long-run economic growth: Evidence from 6,700 cyclones”, NBER Working Paper 20352.

IPCC (2023), “Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report”, Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 35-115,

Klomp, J and K Valckx (2014), “Natural disasters and economic growth: A meta-analysis”, Global Environmental Change 26: 183-195,

Krebel, L, D Kyriakopoulou and J Talbot (2025), “The implications of severe weather events for the economy and monetary policy,” VoxEU.org, 7 February.

OECD (2024), “Accelerating climate adaptation: A framework for assessing and addressing adaptation needs and priorities”, OECD Economic Policy Paper No. 35.

Rosvold, E and H Buhaug (2021), “GDIS, a global dataset of geocoded disaster locations”, Scientific Data 8(61).

Continue Reading

-

Iron reaches record energy state, could power cheaper batteries

Iron, one of Earth’s most common and unassuming metals, has just surprised scientists.

A Stanford-led team has discovered how to push iron into a higher-energy state than ever seen before, a feat that could reshape the future of…

Continue Reading

-

Costume and Urban Roman Dramas Dominate Chinese TV Slate at TIFFCOM

Expect more Chinese epic costume dramas and Shanghai-set modern urban romance dramas in the coming years. And with both genres still at the zenith of their popularity in Asia, why change a winning formula? That seemed to be the message from a…

Continue Reading

-

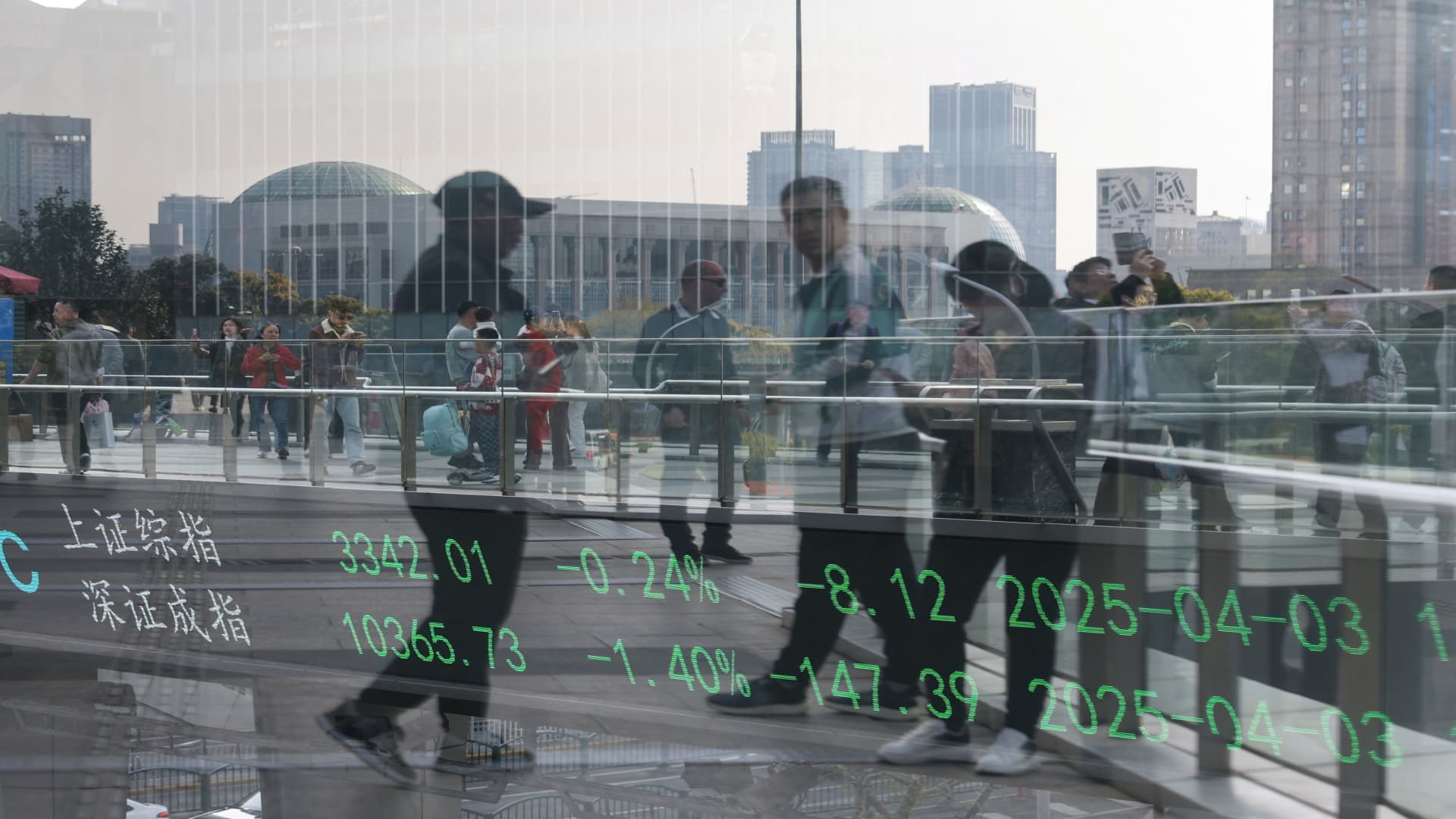

Hang Seng Index, Nifty 50, CSI 300

An electronic board shows Shanghai and Shenzhen stock indices as people walk on a pedestrian bridge at the Lujiazui financial district in Shanghai, China April 3, 2025.

Go Nakamura | Reuters

Asia-Pacific markets opened mostly higher Friday as…

Continue Reading