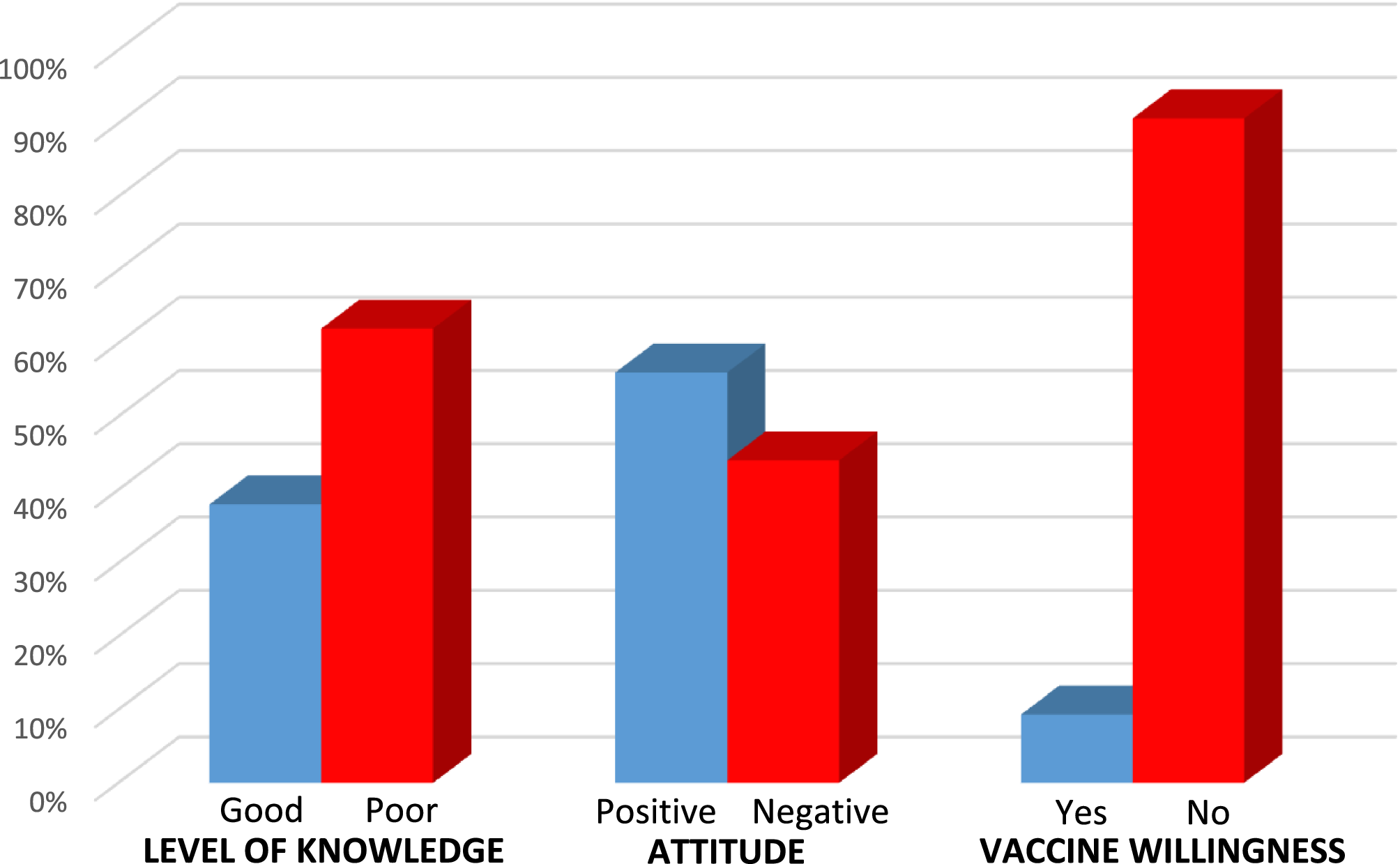

To our knowledge, there is no study in the literature evaluating pregnant women’s knowledge levels, attitudes toward monkeypox disease, and willingness to receive the vaccine. In Türkiye, monkeypox cases have remained very limited, and no large-scale outbreak has occurred. A total of 12 confirmed cases were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) in 2022, and this number has not changed since then. Most of the reported cases involved adult male individuals, and no cases among pregnant women have been documented to date [22]. In our study, 38% of pregnant women were found to have a good knowledge level. In a study by Harapan et al., conducted among physicians, 36.5% of participants demonstrated a good level of knowledge about monkeypox [20]. Similarly, Ricco et al. reported low knowledge levels among participants in their study [23]. Additionally, in a study by Sallam et al., more than half of the healthcare workers answered the knowledge-related questions incorrectly [24].

The low knowledge levels observed among healthcare professionals in these studies may also have indirect implications for pregnant women, as inadequate information or guidance from physicians could contribute to their limited understanding of emerging diseases such as monkeypox.

According to our findings, participants over the age of 33, those with higher education levels, first-time pregnant women, and those who had previously contracted COVID-19 had higher knowledge levels about monkeypox virus. A higher education level, a history of COVID-19 infection, and first gravidity were each associated with a more positive attitude toward monkeypox virus. However, none of the first-time pregnant women were willing to receive the monkeypox vaccine. This may be attributed to their lack of experience, as well as concerns that potential vaccine side effects could harm their baby.

Nath et al. [25], Youssef et al. [26], and Awayomi et al. [27] demonstrated in their studies that higher education levels were associated with better knowledge. This can be explained by education increasing health-related awareness and enabling individuals to make more informed decisions during pandemics that affect large populations. Additionally, better access to information among educated individuals may also play a role.

The association between high gravidity and lower knowledge scores may reflect underlying socioeconomic disparities, as women from lower-income backgrounds may have less access to health information and preventive services. Similarly, the observed differences in knowledge by education level reinforce the importance of targeting educational interventions. In this context, primary care health units can play a pivotal role in disseminating accurate information and promoting awareness, particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged regions.

Several studies have demonstrated that factors such as educational attainment, previous infectious disease exposure (e.g., COVID-19), and gravidity status are associated with variations in health knowledge and vaccine acceptance among pregnant women, particularly during public health emergencies [28, 29]. Our findings are consistent with this evidence, highlighting that higher education level and history of COVID-19 infection were significantly associated with better knowledge and more favorable attitudes toward monkeypox and its vaccination.

Furthermore, awareness of emerging infectious diseases may directly impact preoperative risk assessment and preparation in anesthetic practice, especially in vulnerable populations such as pregnant women [30, 31]. This supports the need for enhanced preoperative counseling and educational interventions during anesthetic evaluations to improve maternal outcomes during outbreaks of emerging infections.

When analyzed by age groups, good knowledge levels and positive attitudes toward monkeypox did not show significant differences. However, willingness to receive the vaccine was significantly higher among participants over the age of 33. In a study by Hasan et al. [32], older participants were also found to have higher rates of positive attitudes toward monkeypox. The reason for the lack of difference in our study could be that pregnant women, regardless of age, actively seek information and search health-related topics out of concern for both their own and their baby’s health.

In our study, 62% of participants perceived COVID-19 as more dangerous than monkeypox. Similarly, a study by Temsah et al. reported that more than 60% of participants shared this view [16]. The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health and the economy has been profound [33]. The reemergence of monkeypox has raised concerns about the potential for another pandemic, particularly following the COVID-19 crisis.

A positive attitude toward monkeypox virus was observed in 56% of participants. In previous studies, Jamil et al. [34] and Şahin et al. [35] reported 41.7%, while Das et al. [36] found 51.1% of participants exhibiting a positive attitude. Differences in these rates may be attributed to sample size, geographic location, and population characteristics.

A history of COVID-19 infection was not associated with better knowledge levels or increased vaccine willingness regarding monkeypox. However, it was significantly correlated with a more positive attitude. Pregnant women who had experienced COVID-19 may have been more aware of the severity of viral diseases and more open to acquiring knowledge, which may have contributed to their positive attitude. Studies by Bonner et al. [37] and Patwary et al. [38] also demonstrated that awareness of disease severity increases vaccine willingness. The different result in our study may be due to participants being pregnant and therefore having concerns about potential vaccine side effects.

In our study, the majority of participants (78%) stated that they would not receive the monkeypox vaccine during pregnancy. However, a significant proportion of participants expressed that their decision could be influenced by recommendations from healthcare professionals and the vaccination choices of other pregnant women. The free availability of the vaccine was not a determining factor in their decision.

Healthcare professionals, particularly obstetricians, should provide targeted counseling during prenatal visits to address concerns and misconceptions regarding monkeypox vaccination. Moreover, public health authorities should consider launching coordinated campaigns via social media and traditional channels to enhance awareness and promote vaccine acceptance. Special emphasis should be placed on reaching first-time pregnant women and those with lower education levels.

Our findings also have implications for anesthetic practice. Awareness of monkeypox virus among pregnant women can directly impact preoperative risk assessment and perioperative management. In cases of suspected or confirmed infection, anesthetic techniques may need to be adapted, isolation precautions considered, and surgical timing carefully evaluated to minimize both maternal and neonatal risks. Therefore, enhancing knowledge and addressing concerns regarding infectious diseases among pregnant women supports not only general public health, but also safe and effective anesthetic care.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single tertiary hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader pregnant population. Second, information bias may have occurred due to the self-reported nature of the survey. Third, the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships. Finally, the knowledge and attitudes of the participants may have been influenced by contemporaneous media coverage regarding monkeypox. Finally, voluntary participation may have introduced self-selection bias, as women with greater health awareness and interest in vaccination topics may have been more likely to participate.