TALES FROM THE CLINIC

-Series Editor Nidal Moukaddam, MD, PhD

In this installment of Tales From the Clinic: The Art of Psychiatry, we discuss Huntington disease (HD). While the motor pathology is easily clinically recognizable, associated neuropsychiatric manifestations are not well understood and lack systematic treatment trials, despite representing a significant burden on patients. HD also lacks disease-modifying therapies.

Case Study

“Mr John” is a 44-year-old man with a 5 year history of major depressive disorder who presents to his psychiatrist after referral from his primary care physician. He presents with concerns regarding a new onset of cognitive deficits. He reports that he has recently noticed difficulty focusing and has also become very forgetful, missing appointments for his job. Mr John states that this has been ongoing for several weeks now and has been experiencing trouble at work because of it. He is worried that it might be because of his recent increase in fluoxetine from 20-mg to 30-mg daily due to his worsening depressive symptoms. Mr John denies any physical/motor symptoms such as tremors or involuntary movements and denies headaches. He does report that he has become more anxious and irritable lately. Family history is positive for suicide of mother at age 44.

His psychiatrist performed the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Mr John received a score of 21, indicating mild cognitive impairment. In light of this, his psychiatrist makes another referral to a neurologist to address this new-onset of cognitive symptoms. Upon his visit to the clinic, the neurologist performs a full neurological exam and notes no major deficits in motor function. The neurologist asks Mr John again about his family history. Mr John reports that his mother had regular mood swings and committed suicide around his age. When asked about his grandparents, he states that he does not remember much aside from his maternal grandfather often making random “jerky” movements.

The neurologist orders a genetic test which comes back positive for a HTT mutation, confirming that Mr John has HD. The neurologist counseled Mr John about the prognosis of HD and the progession of its symptomology to the triad of motor, psychiatric, and cognitive symptoms. He is prescribed memantine 20-mg daily for his cognitive deficits and continues his fluoxetine 30-mg daily. His neurologist and psychiatrist work together and monitor Mr John’s disease progression, prepared to add new medications as needed.

5-Year Follow Up

Mr John presents to his neurologist having now developed full HD pathology. He is on an extensive medication regimen with dopamine modulators, NMDA receptor antagonists, anti-depressants, and anxiolytics. His neurologist informs Mr John of an upcoming clinical trial for gene therapy with the potential of inactivating mHTT and helps him get enrolled.

What Is HD?

HD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease of the basal ganglia that manifests in disturbances of cognitive, motor, and behavioral/psychiatric functions, leading to severe disability and ultimately death.1,2 It occurs with its highest prevalence in Western populations at 10.6-13.7 individuals per 100,000 with a global rise over the past 2 decades.1,2 The disease is caused by a CAG trinucleotide repeat expansion on chromosome 4 of the HTT gene, creating a mutant huntingtin (mHTT) protein that is responsible for the disease pathology.1,2 Several proposed mechanisms ranging from glutamine excitotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation have been advanced to explain the clinical manifestations.2,3 Ultimately, the striatum’s neuronal population of medium spiny neurons (MSNs) become vulnerable as a result of the mHTT protein and undergo neurodegeneration. As a disease of the basal ganglia, the molecular progression of HD is biphasic, starting with the loss of the indirect pathway of the basal ganglia and progressing to the direct pathway. The neurodegeneration and subsequent inactivation of the basal ganglia pathways lead to atrophy of the caudate nucleus and putamen. HD also displays monogenic autosomal dominant inheritance with full penetrance, meaning the disease is always expressed as long as an individual has at least 1 copy of the gene/allele.2

HD symptomology follows a triad of motor, cognitive, and psychiatric/behavioral disturbances, usually manifesting during mid-adulthood.1-3 The biphasic progression of HD manifests to a and early hyperkinetic phase of involuntary movements (ie, chorea) and a later hypokinetic phase where voluntary movements become inhibited, resulting in bradykinesia, dystonia, gait disturbances, etc.1,2 Cognitively, HD results in impaired emotional processing as well as executive function (ie, attention, concentration, decision making, etc) with some evidence of indirect PNS impairment.1,2 HD has a wide psychiatric manifestation, with notable effects on anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive behavior, irritability, aggression, and psychosis.1,2 The actual diagnosis of HD can be made at any time, but it is typically done during middle adulthood after the onset of symptoms.3 Given the genetic nature of HD, clinical diagnosis is usually evaluated by a positive genetic test for the HTT mutation in combination with cognitive tests and neuroimaging.1,2 Predictive testing prior to symptom onset could also be done for individuals at risk of inheriting the mutation, typically for reproductive purposes.1

Currently, there are no approved disease-modifying treatments for HD; therefore, the therapeutic interventions only address the actual symptoms.3 Treatment for motor symptoms are limited to supplementing the indirect pathway (ie, hyperkinesia and chorea) via dopamine modulators/antagonists as well as antiglutamatergic drugs. Given the mechanism of the basal ganglia pathways, the therapy for the indirect pathway could exacerbate the symptoms of the direct pathways (ie, hypokinesia and rigidity). Dopamine agonists have been studied, although they have limited effect.3 Cognitive impairment is typically treated with NMDA receptor antagonists (eg, memantine), which reduces the glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity.3 Psychiatric and behavioral treatment options typically follow the general therapeutics of the specific symptoms (ie, antidepressants, antipsychotics, etc).3

Advancements in gene therapies, specifically CRISPR associated protein 9 (Cas9), show promise in possible disease-modifying therapies via inactivation of mHTT.3 HD is a fully penetrant disease with a very poor prognosis. The disease itself is progressive and the symptomatology has a profound effect on quality of life.1,2 While the specific gene of HTT has been identified, the actual mechanism leading to the neurodegeneration of striatal MSNs remains unclear, leading to limited treatment options aside from developing gene therapies and addressing the symptoms.1, 2, 3

Clinical Practice and Treatment

While HD is certainly an area of academic interest, the management of its neuropsychiatric symptoms is not as well explored as its motor or cognitive manifestations.4 Psychiatric—or rather, neuropsychiatric—symptoms are not just common in patients with HD, but are part of the full disease spectrum (ie. triad) and cause serious emotional toll and distress.5 In fact, neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) are often the very first manifestation of HD, occurring in atypical phases as early as 20 years before the onset of motor symptoms (eg, chorea).6 Regarding the mechanism, studies point towards the neuronal loss of the basal ganglia and eventual cerebral degeneration as a core contributor to NPS. The resulting neurodegeneration seems to affect other neuronal pathways such as the limbic system, the orbitofrontal-subcortical circuit, and the anterior cingulate-subcortical circuit structures, just to name a few.6 As far as the scope of NPS, we see a wide range of symptomatology including affective and nonaffective disorders such as depression, mania, and anxiety.6,7 Furthermore, other behavioral symptoms such as apathy, impulsivity, disinhibition, and sexual dysfunction as well as obsessive and psychotic symptoms are reported.6,7 The heterogeneous and complex nature of NPS manifestation in HD makes it especially difficult to manage in terms of pharmacotherapy.5 On top of that, there is a severe lack of evidence-based clinical trials for disease modifying therapies which makes pharmacological treatment especially limited.8

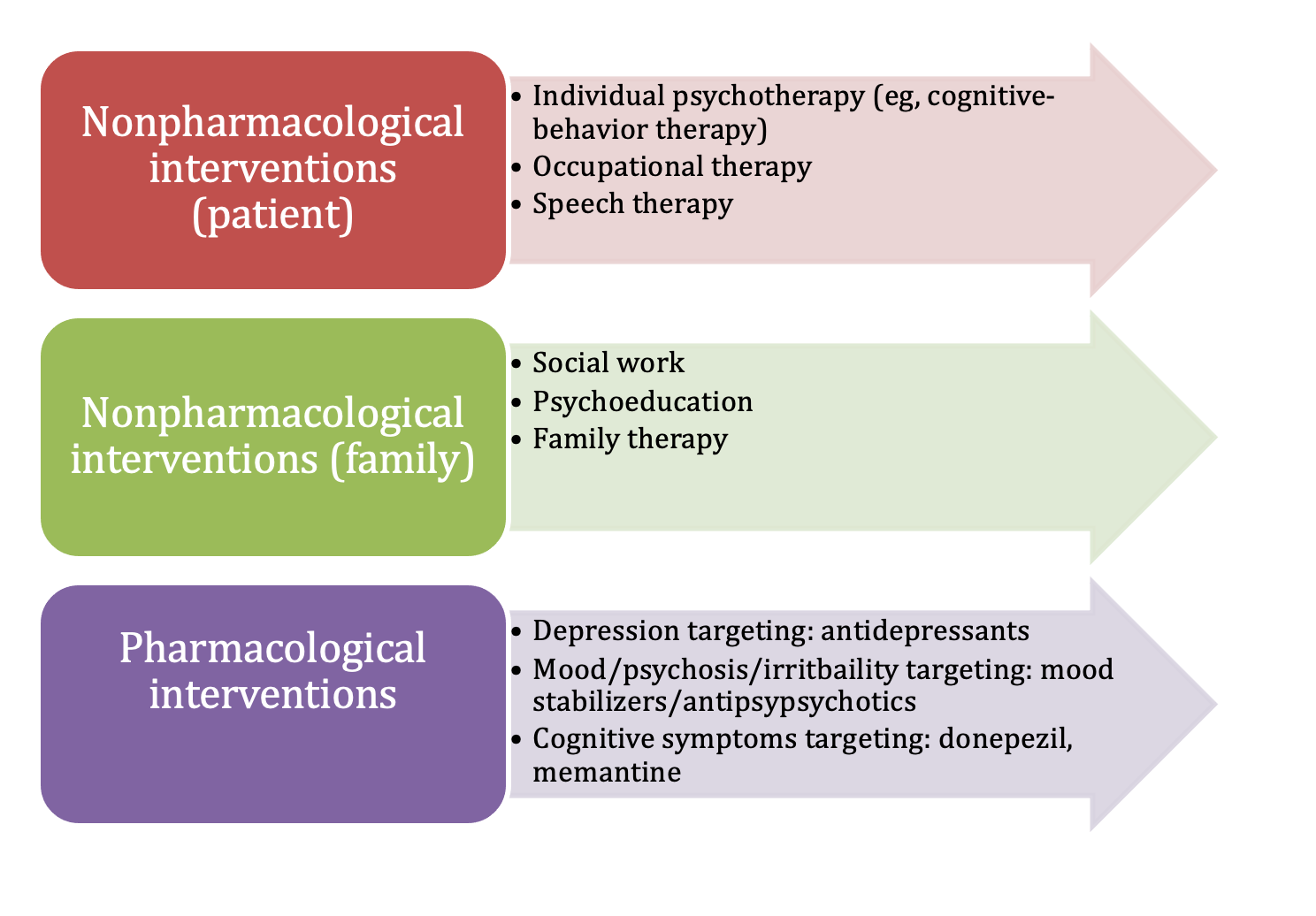

Generally, it is imperative for the physician to identify any NPS as early as possible and begin treatment, following the multidisciplinary approach of pharmacological interventions as well as counseling, behavioral therapy, and support.4 Depression is the most common NPS seen in HD, appearing in atypical stages throughout the disease, normally preceding any motor symptoms as a prodrome and eventually increasing during the disease course.9 Anxiety in HD is also common, usually coexisting with depression in the prodromal stage, and can actually worsen the eventual motor and cognitive HD symptoms.5 Irritability/aggression is another especially common NPS in HD, where patients are very quick to anger despite minimal triggers.9 On the other side of the coin, we see apathy as another extremely frequent NPS that occurs in the middle and later stages of the disease. In this case, patients will greatly lose interest and motivation in daily activities.9 These specific NPS are typically linked together and contribute to a significant increase in risk factor for suicide in patients with HD, with a suicide rate 4 to 5 times higher than the general population.6 Obsessive compulsive symptoms and psychotic symptoms have also been documented in patients with HD, although they are less common than other NPS.6 The recommended pharmacological therapies follow the standard guidelines per psychiatric symptom (eg, SSRIs for depression), with disease modifying treatment being severely understudied.8 Furthermore, with the diverse scope of NPS, it is imperative to always monitor drug interactions to prevent adverse reactions or exacerbated symptoms.6 With that in mind, it is also important to consider the guidelines on behavioral therapies as treatments for specific NPS in patients with HD.5 Cognitive symptoms can also occur, and present in a dementia-like picture in advanced stages. The Figure outlines first line pharmacological treatments as well as alternative drug classes and behavioral interventions.4,5,10

Figure. Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms Associated With HD

Concluding Thoughts

While HD is often characterized by its motor symptoms of hyperkinetic movement and chorea, it has major psychiatric manifestations that are just as common and extremely burdensome on the patient. Psychiatrists treating patients with HD can expect to find symptoms of depression, anxiety, agitation, apathy, obsessive-compulsion, and even psychosis; however, the actual range of neuropsychiatric symptoms is even more broad. When treating patients with HD for their psychiatric manifestations, it is imperative to follow the most up-to-date guidelines on pharmacological therapies, paying close attention to drug-drug interactions and paradoxical effects.10 Given the extensive symptomology, certain drug classes may alleviate one set of symptoms while exacerbating another. Furthermore, physicians in general must always take an interdisciplinary approach to care and help the patient manage symptoms through traditional behavioral/psychological therapies.

In HD, neuropsychiatric symptoms often precede any motor symptoms, which can make psychiatrists the first responders. With that said, psychiatrists must be able to spot the pattern of HD NPS and make the necessary orders and referrals to ensure the best patient outcome. For example, a psychiatrist may note that a patient presents as presymptomatic for HD and can order a genetic test. Throughout their treatment, patients with HD can be seeing several different physicians at a time, as well as be taking multiple medications simultaneously. As such, psychiatrists and neurologists must work in deep collaboration between themselves and their patients to ensure efficient drug management and proper care.

The mechanism behind HD is unfortunately elusive and there is no actual disease modifying therapy available for patients, with only symptom addressing therapeutic interventions available. Even so, pharmacological treatment plans also lack the evidence from clinical trials to adequately address the neuropsychiatric symptoms of HD. Current research points towards gene therapies such as CRISPR associated protein 9 (Cas9) as having the potential to treat patients with HD at the molecular level. With limited treatment options available, physicians must dedicate their support to advancing HD research in clinical trials and beyond. Support for families may also be welcome as symptoms become more pronounced.

Mr Saadah is a student at TAMU College of Medicine, interested in neurology/psychiatry interface. Dr Moukaddam is a professor of psychiatry at Baylor College of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, and the Director of Outpatient Psychiatry at Harris Health. She also serves on the Psychiatric Times Editorial Board.

References

1. McColgan P, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington’s disease: a clinical review. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(1):24-34.

2. Jiang A, Handley RR, Lehnert K, Snell RG. From pathogenesis to therapeutics: a review of 150 years of Huntington’s disease research. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):13021.

3. Kim A, Lalonde K, Truesdell A, et al. New avenues for the treatment of Huntington’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(16):8363.

4. Jay JA, Kumar V, Garrels E, et al. Management of neuropsychiatric disturbances in Huntington’s disease: a literature review and case report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2023;25(1):22cr03265.

5. Anderson KE, van Duijn E, Craufurd D, et al. Clinical management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of Huntington disease: expert-based consensus guidelines on agitation, anxiety, apathy, psychosis and sleep disorders. J Huntingtons Dis. 2018;7(3):355-366.

6. Paoli RA, Botturi A, Ciammola A, et al. Neuropsychiatric burden in Huntington’s disease. Brain Sci. 2017;7(6):67.

7. Saft C, Burgunder JM, Dose M, et al. Symptomatic treatment options for Huntington’s disease (guidelines of the German Neurological Society). Neurol Res Pract. 2023;5(1):61.

8. Andriessen RL, Oosterloo M, Molema J, et al. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Huntington’s disease: a systematic review. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2025;12(4):418-431.

9. Bachoud-Lévi AC, Ferreira J, Massart R, et al. International guidelines for the treatment of Huntington’s disease. Front Neurol. 2019;10:710.

10. Lopez MA. Huntington disease (HD). Rare Disease Advisor. Updated June 24, 2025. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.rarediseaseadvisor.com/junction-hub-pages/huntington-disease/