According to our findings, the lifetime prevalence of any mental disorders was 19.16%, while the 12-month prevalence was 10.62%. Anxiety disorders were the most prevalent mental disorders, followed by mood disorders and substance use disorders. Furthermore, the distribution of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders varied across different genders and age groups. Age, the number of chronic diseases, chronic pain, and sleep disturbances were significantly associated with the 12-month prevalence of any mental disorders.

After entering the twenty-first century, studies that comprehensively investigate the prevalence of mental disorders among the elderly in China remain remarkably scarce. Studies examining any mental disorders in different provinces revealed a lifetime prevalence of 24.20% in Tianjin [12] and 21.9% in Hebei [6], which both had a higher prevalence than our study. The mental disorders in Hebei survey mainly included anxiety disorders, mood disorders, substance use disorders and psychotic disorders. However, the Tianjin survey included dementia and mental retardation, which were excluded from our analysis due to methodological differences. Moreover, the lifetime prevalence rates of anxiety disorders identified in the Tianjin and Hebei surveys were 3.71% and 10.13%, respectively. Similarly, the lifetime prevalence of mood disorders and substance use disorders were 9.75% and 5.58% in Tianjin, and 7.73% and 7.48% in Hebei, respectively. These findings are difficult to compare directly with our results due to these differences. Therefore, broader investigations are needed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the prevalence of mental disorders among the elderly population in China. When compared with other countries, the prevalence of mental disorders among Chinese elderly population aligns with that of other Asian nations but remains notably lower than in Western counterparts. For instance, in Singapore, the lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders (including major depressive, bipolar, generalized anxiety, obsessive–compulsive and alcohol use disorders) [31] among adults aged 50 years and above were 7.9% and 3.1%, respectively, with a downward trend observed in older age groups. In contrast, among European elderly aged 65 to 84 years, the lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders (primarily anxiety, mood and substance use disorders) were 47.0% and 35.2%, respectively [32]. The 12-month prevalence of anxiety, mood and substance use disorders were 25.6%, 14.3% and 18.2% among the European elderly [32], compared to 11.39%, 6.77%and 3.75% among American adults aged 55 years old and above [21].

This finding aligns with previous study showing that the prevalence of mental disorders in Asia is generally lower than in Western countries [33]. Several factors may explain this difference. First, the multi-ethnic nature of Asia may lead to genetic polymorphism, and the genetic susceptibility of the Asian population to mental disorders may differ from Western populations [34]. Second, Asian cultures typically emphasize family and community values, which may provide stronger social and psychological support for individuals, thereby reducing the incidence of mental disorders. At the same time, Asian cultural values, especially Chinese cultural values, are also associated with greater stigma surrounding mental disorders. This stigma often leads to reluctance to acknowledge mental health issues or seek treatment [33].

In contrast to European findings, our study reported a notably lower prevalence of mental disorders among older adults. Several factors elucidate these cross-regional discrepancies. European research highlights that historical underestimation of geriatric mental disorder prevalence stemmed from non-age-adapted assessment tools [33]. The CIDI65 + interview used in Europe, featuring simplified language, improved response validity and uncovered higher prevalence. By contrast, the standard CIDI used in our study lacks age-specific adaptations, which may have caused partial misinterpretation of questions by older adults and potentially underestimated prevalence. The challenge of non-response bias complicates prevalence data interpretation. Global studies on non-response and mental disorder prevalence are inconsistent: some show higher rates among non-responders [35], while others report no significant link [36], suggesting estimates may be conservative if bias exists. Moreover, a cross-sectional study in China [37] revealed that a significant proportion of Chinese individuals hold negative attitudes toward people with mental illnesses, highlighting that cultural stigma around mental health is a critical factor contributing to underreporting. These multifaceted influences highlight the necessity of adopting culturally sensitive and methodologically robust approaches in future mental health research.

According to our findings, the 12-month prevalence of different mental disorders among the elderly population varied significantly by age and gender. First, it was notable that anxiety disorders were more prevalent among individuals aged 55–64 years than among those aged 65 years and older. The finding was partly consistent with previous studies, which have shown that the prevalence of anxiety disorders decreases with increasing age, particularly with a significant drop observed in individuals aged 75 years and older [38]. As is well known, individuals entering the”young old”age group begin to experience neurobiological changes, along with an increase in physical illnesses and cognitive decline, all of which are associated with anxiety disorders in aging populations [39]. Their psychological adjustment abilities may not yet be well-developed, which could explain the higher prevalence of anxiety disorders in the 55–64 age group. Unlike previous studies that typically set 60 or 65 as the starting point of old age, our study defined the beginning of old age as 55. Consequently, we found that the prevalence among individuals aged 55–59 was as high as those aged 60–64, suggesting that interventions for anxiety disorders should target the’young old.

Our results also indicate that age plays a significant role in the prevalence of any mental disorders, with increasing age (≥ 70 years) associated with a reduced risk of these disorders. This finding is partly in line with some studies in this area [32], which have similarly observed a decline in the prevalence of mental disorders in individuals aged 75 years and older. Although the ageing process reduces the capacity of the elderly to cope with stressful life events, the oldest-old tend to have higher resilience and more optimistic than the young-old [40]. In contrast, two studies from India and Brazil have shown that the prevalence of mental disorder was significant higher in older people(> 80 years old) [41, 42]. This discrepancy may be attributed to socio-economic factors, such as reduced functional ability in older adults due to limited economic development and inadequacies in pension systems.

Secondly, mood disorders were more common in female than male, which was in line with a handful of comparable studies in this area [43]. This difference may be attributed to greater emotional sensitivity, negative emotional experiences associated with childbirth, menopause, and other unique life stages in women compared to men [44].

Thirdly, substance use disorders were more prevalent in male and decreased with increasing age, which may be related to Chinese “wine culture”. Notably, substance use disorders in the Chinese population are primarily associated with alcohol use [20]. And a large proportion of studies had shown that alcohol use decreased as individuals age [30]. This decrease may be attributed to the adverse outcomes of drinking becoming more pronounced with age, leading to a decline in health status among older adults. Moreover, the liver’s ability to metabolize alcohol diminishes with age, resulting in reduced alcohol consumption.

Notably, our study demonstrated scant significant variations in the prevalence of mental disorders between elderly individuals residing in urban and rural areas. This finding aligns with previous analyses of the CMHS dataset, which reported no significant urban–rural disparities in the prevalence of most mental disorders (including mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders) [21]. Our results also resonate with a Korean study, which found no significant differences in the prevalence of depression between urban and rural samples [45]. In contrast, a 2001–2005 Chinese study that utilized the SCID to diagnose all mental disorders reported higher prevalence of depressive disorders and alcohol dependence among rural residents [23]. Several factors may account for this discrepancy. First, rapid socioeconomic development in rural areas has improved healthcare access and mitigated historical stressors [46]. Methodologically, the SCID used in the prior study [23] likely detects symptoms of certain disorders, such as bipolar disorders and anorexia nervosa, more sensitively than the CIDI [47]. Additionally, lower literacy among rural older adults may have caused misinterpretations of CIDI questions, leading to underreporting.

The distribution of the 12-month prevalence of different mental disorders provides a more accurate depiction of the mental health status of the elderly. Furthermore, our results emphasize the importance of addressing chronic diseases, pain, and sleep disturbances as part of strategies to prevent mental disorders in this population. Contrary to some prior studies linking low income to mental disorders [48, 49], our findings did not identify income as a significant correlate of mental disorders among the elderly in China. This divergence may stem from the relatively homogeneous socio-economic status within the China Mental Health Survey (CMHS) sample or from cultural factors, such as stigma, that influence the reporting and perception of mental health issues in this population.

Our results were concordant with previous studies showing that having diagnosis of chronic non communicable disease is associated with a higher risk of mental disorders, with the risk increasing further for individuals with three or more chronic conditions [50]. At the same time, our study found that pain was associated with higher odds of mental disorders, consistent with previous findings that highlight the relationship between pain and mental health [51]. Comorbidity and pain can amplify the painful experience of the individual, increasing the risk of mental illness. Furthermore, comorbid conditions and pain reduce physical activity, which in turn diminishes executive functioning and exacerbates mental disorders [52].

Similarly, our findings align with numerous studies confirming that sleep problem is a significant predictor for the onset of mental disorders, particularly depression, followed by anxiety and substance use disorders [42]. Studies have also shown that greater insomnia severity predicts an increased likelihood of developing depressive and anxiety disorders. Importantly, adults aged 55 and older account for 80% of all individuals with insomnia [53], emphasizing the critical need to investigate the relationship between insomnia and mental disorders and to address sleep issues among the older population. Nonetheless, the mechanisms linking insomnia to mental disorders remain incompletely explained. Some potential explanations are as follows On a physiological level, wake-sleep regulation and mental disorders share specific neuronal pathways, neurotransmitters, and receptors [54]. On a genetic and environmental level, depression and insomnia overlap in terms of genetic predispositions and environmental influences [55]. On a psychological level, stress and adversity are strongly associated with the co-occurrence of insomnia and depression [55].

In summary, it is essential to integrate mental disorder screening into aging-related disease assessments, particularly setting 55 years old as the starting age, which can be highly meaningful for public health.

Limitations and strength

There are several limitations deserve to be concerned. First, as with other cross-sectional studies, retrospective reporting may cause recall bias or influenced by current mental state when diagnose lifetime mental disorders. Cognitive decline in the elderly may increase the influence, though interviewers recorded mental state during interviews to mitigate its impact. Second, our study was based on community population, which excluded institutionalized elderly individuals. This exclusion may have limited the generalizability of our findings. Third, Chinese cultural values, which are associated with greater stigma surrounding mental disorders, may have influenced the reported prevalence rates. Additionally, the data were collected ten years ago. Since that time, China has experienced significant economic growth as well as advances in medicine and technology, which may impact the current relevance and generalizability of these findings. However, the CHMS remains the most recent nationally representative survey available and still provides important insights into the phenomenon studied. Lastly, the survey’s limited generalizability resulted from the exclusion of mental disorders such as dementia in our CIDI assessment. Finally, the family history of mental disorders, a known risk factor, was not collected in this study.

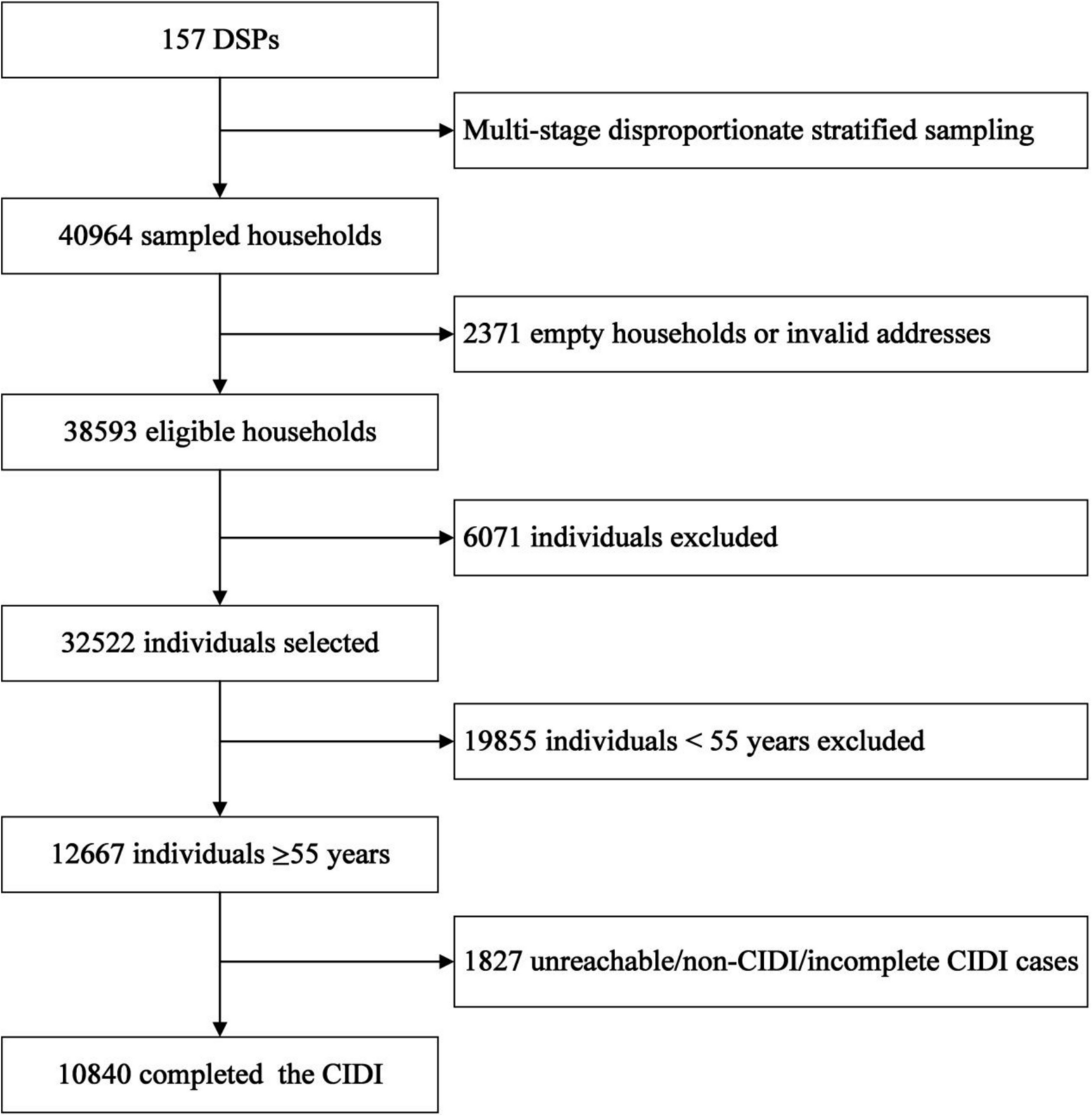

Despite its limitations, our study presents several significant strengths. First, in contrast to previous research that predominantly centered on mental symptoms, this study employed standardized diagnostic tools to investigate the prevalence of mental disorders among Chinese elderly, ensuring a more accurate and clinically relevant assessment. Second, by comprehensively collecting a wide range of variables, including demographic information, physical diseases, and other related factors, our study offers a holistic understanding of the determinants contributing to mental health issues in the elderly. Additionally, defining the”young old”as individuals aged 55 and above offers a precise basis for targeted prevention strategies, enabling early interventions attuned to this vulnerable group’s mental health needs.