Since the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) was established in 1988, it has presented a roadmap to achieving a world free of all forms of poliovirus.

For 2022-2026, the GPEI strategy has two clear goals: Interrupt All Poliovirus Transmission in Endemic Countries, and Stop Transmission of Variant Poliovirus and Prevent Outbreaks in Non-endemic countries.

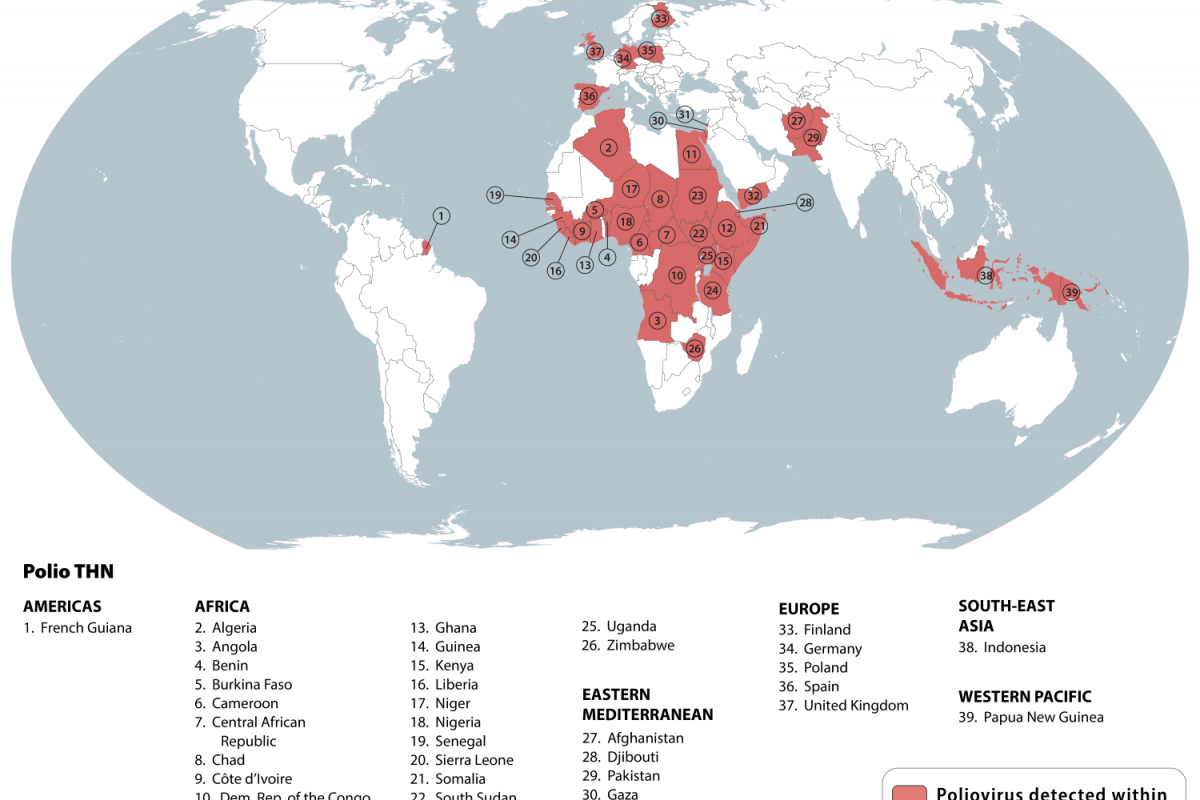

These GPEI goals are being challenged as 39 countries were recently identified by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as being at-risk for poliovirus.

According to an article published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases on August 13, 2025, funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the use of Sabin-strain oral poliovirus vaccines (OPVs) for immunisation has drastically reduced the burden of poliomyelitis and transmission of poliovirus.

It has made a significant contribution to the eradication of types 2 and 3 wild polioviruses.

These vaccines provide individual protection and interrupt person-to-person transmission of polioviruses.

However, on infrequent occasions, use of OPVs can result in vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) or paralytic outbreaks due to circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (VDPVs).

Central to both VAPP and circulating VDPV-induced disease is reversion of the vaccine strain to a more neurovirulent phenotype during intestinal replication of the virus.

In the case of circulating VDPVs, reverted viruses can be transmitted to household or community contacts and cause disease outbreaks in settings of persistently poor immunisation coverage.

To address these issues, researchers conducted a first-in-human, observer-masked, multicentre, phase 1 randomised controlled trial in healthy adults at four centres in the USA.

Participants were block randomised, stratified by site and according to polio vaccination history (inactivated poliovirus vaccine [IPV] only or regimens including OPV, and randomly assigned to receive either novel OPV (nOPV) or homotypic Sabin-strain monovalent OPV (mOPV).

They found that nOPV1 and nOPV3 were safe, well-tolerated, and induced similar immunogenicity to their Sabin controls. The magnitude and duration of nOPV shedding were not higher than with Sabin controls.

They also observed a reduction in shedding following the second dose, which is consistent with the enhancement of intestinal immunity.

These researchers wrote that the successful deployment of nOPV2 to combat type 2 circulating VDPVs in the last few years suggests that use of such novel vaccines could be effective in the control of circulating VDPV outbreaks after the cessation of vaccines containing Sabin-strain types 1 and 3 polioviruses.

nOPVs can thus support the Polio Endgame Strategy by providing outbreak response vaccines that are less likely to be associated with VAPP and seeding of new circulating VDPVs.

The safety and immunogenicity evidence generated for nOPV1 and nOPV3 in this phase 1 clinical study were sufficient to justify the now ongoing phase 2 studies in geographically relevant target populations of previously vaccinated children and infants, as well as vaccine-naive neonates, concluded these researchers.

As of August 15, 2025, the IPV is offered in the United States, and the nOPV2 vaccine has been deployed over 1 billion times in select countries.

And in the Pacific Region, Papua New Guinea recently launched a nationwide immunization campaign to protect nearly 3 million children against polio. Detections of variant type 2 poliovirus have been confirmed through environmental and community surveillance.

In 17 high-risk areas, two rounds of vaccination were conducted using both the nOPV2 and the IPV.

And in the New Guinea Islands Provinces, a single round of IPV was offered.

The WHO wrote, It is working hand-in-hand with the Government of Papua New Guinea and partners to ensure the campaign’s success.’