Bilawal praised SIUT’s partnership with Sindh govt, calling it province’s ‘most powerful public-private collaboration’

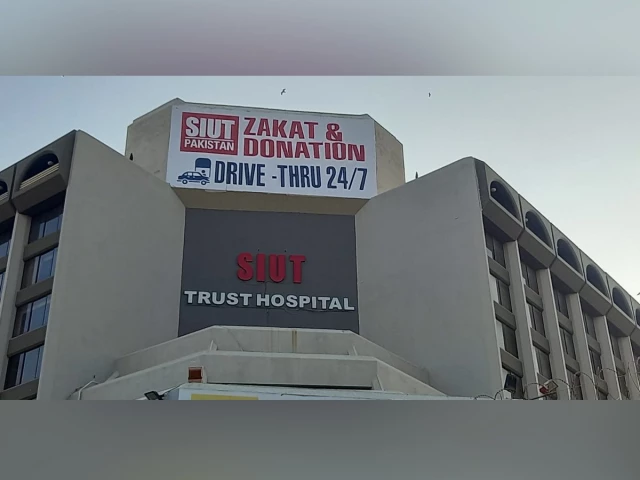

The Sindh Institute of Urology…

Bilawal praised SIUT’s partnership with Sindh govt, calling it province’s ‘most powerful public-private collaboration’

The Sindh Institute of Urology…