Restricted blood flow speeds tumor growth by aging the immune system. The findings highlight risks for patients with vascular disease and potential new therapies.

A new study from NYU Langone Health reports that restricted blood flow can accelerate the aging of bone marrow, reducing the immune system’s ability to combat cancer.

The research, published on August 19 in JACC-CardioOncology, found that peripheral ischemia—restricted circulation in the arteries of the legs—caused breast tumors in mice to grow at twice the rate observed in mice with normal blood flow. These results build on a 2020 investigation by the same team, which showed that ischemia during a heart attack produced similar effects.

How ischemia develops

Ischemia develops when fatty substances, such as cholesterol, build up inside artery walls. This buildup triggers inflammation and clot formation, which limit the delivery of oxygen-rich blood. When ischemia occurs in the legs, it results in peripheral artery disease, a condition that affects millions of Americans and raises the likelihood of heart attack or stroke.

“Our study shows that impaired blood flow drives cancer growth regardless of where it happens in the body,” says corresponding author Kathryn J. Moore, PhD, the Jean and David Blechman Professor of Cardiology in the Department of Medicine, Leon H. Charney Division of Cardiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine. “This link between peripheral artery disease and breast cancer growth underscores the critical importance of addressing metabolic and vascular risk factors as part of a comprehensive cancer treatment strategy.”

The investigators also discovered that restricted circulation shifts the balance of immune cell populations in a way that weakens the body’s ability to fight infections and cancer. These alterations closely resemble the changes in immune function that normally occur with aging.

Systemic skewing of immune cells

To investigate how cardiovascular disease influences cancer progression, the researchers created a mouse model carrying breast tumors and induced temporary ischemia in one hind limb. They then compared tumor development between animals with restricted circulation and those with normal blood flow.

The results expand on what is known about the immune system, which has evolved to defend against invading bacteria and viruses and, under healthy conditions, to recognize and destroy cancer cells. These defense mechanisms depend on stem cell reserves in the bone marrow that can be activated when needed to generate crucial white blood cell populations throughout life.

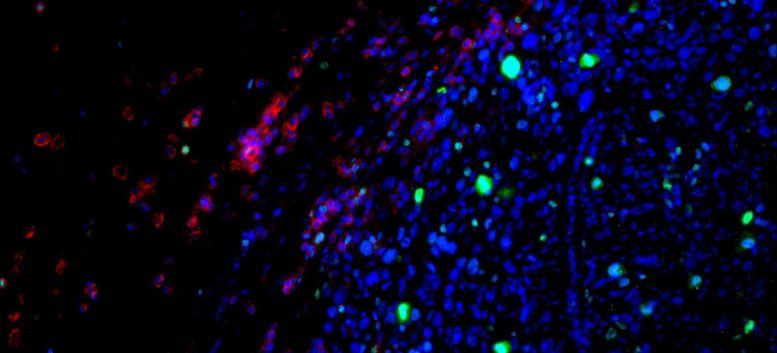

Under typical circumstances, the immune system counters infection or injury by increasing inflammation to eliminate harmful agents and later scaling it back to protect healthy tissue. This balance relies on a mixture of immune cells that either amplify or suppress inflammation. The investigators discovered that limited blood flow disrupts this equilibrium by reprogramming bone marrow stem cells. The shift favors the production of “myeloid” immune cells (monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils), which weaken immune defenses, while decreasing the generation of lymphocytes such as T cells that are vital for mounting strong anti-cancer responses.

Tumor environment shifts toward suppression

The local environment within tumors showed a similar shift, accumulating more immune-suppressive cells– including Ly6Chi monocytes, M2-like F4/80+ MHCIIlo macrophages, and regulatory T cells – that shield cancer from immune attack.

Further experiments showed that these immune changes were long-lasting. Ischemia not only altered the expression of hundreds of genes, shifting immune cells into a more cancer-tolerant state, but also reorganized the structure of chromatin–the protein scaffolding that controls access to DNA–making it harder for immune cells to activate genes involved in fighting cancer.

“Our results reveal a direct mechanism by which ischemia drives cancer growth, reprogramming stem cells in ways that resemble aging and promote immune tolerance,” says first author Alexandra Newman, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Dr. Moore’s lab. “These findings open the door to new strategies in cancer prevention and treatment, like earlier cancer screening for patients with peripheral artery disease and using inflammation-modulating therapies to counter these effects.”

Moving forward, the research team hopes to help design clinical studies that evaluate whether existing inflammation-targeted therapies can counter post-ischemic changes driving tumor growth.

Reference: “Cancer Development in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: JACC: CardioOncology Short-Form Primer” by Jessie M. Dalman, BA and Kathryn J. Moore, 19 August 2025, Cardio Oncology.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2025.05.016

The study was supported by American Heart Association grants 915560, 25CDA1437452, 23POST1029885, 25PRE1373174, and 23SCEFIA1153739; as well as by National Institutes of Health grants T32GM136542, F30HL167568, T32HL098129; R01 HL151078, R01 HL161185, R35 HL161185, R01HL153712, R01HL172335, R01HL172365, and P01HL131481. The work was also supported by the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation, the LeDucq Foundation Network, and Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center support grant P30CA016087.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.