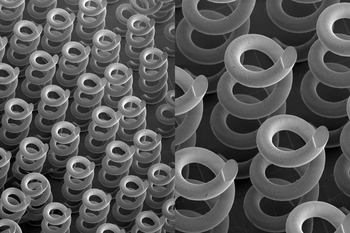

Newswise — Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) have optimized and 3D-printed helix structures as optical materials for Terahertz (THz) frequencies, a potential way to address a technology…

Newswise — Researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) have optimized and 3D-printed helix structures as optical materials for Terahertz (THz) frequencies, a potential way to address a technology…