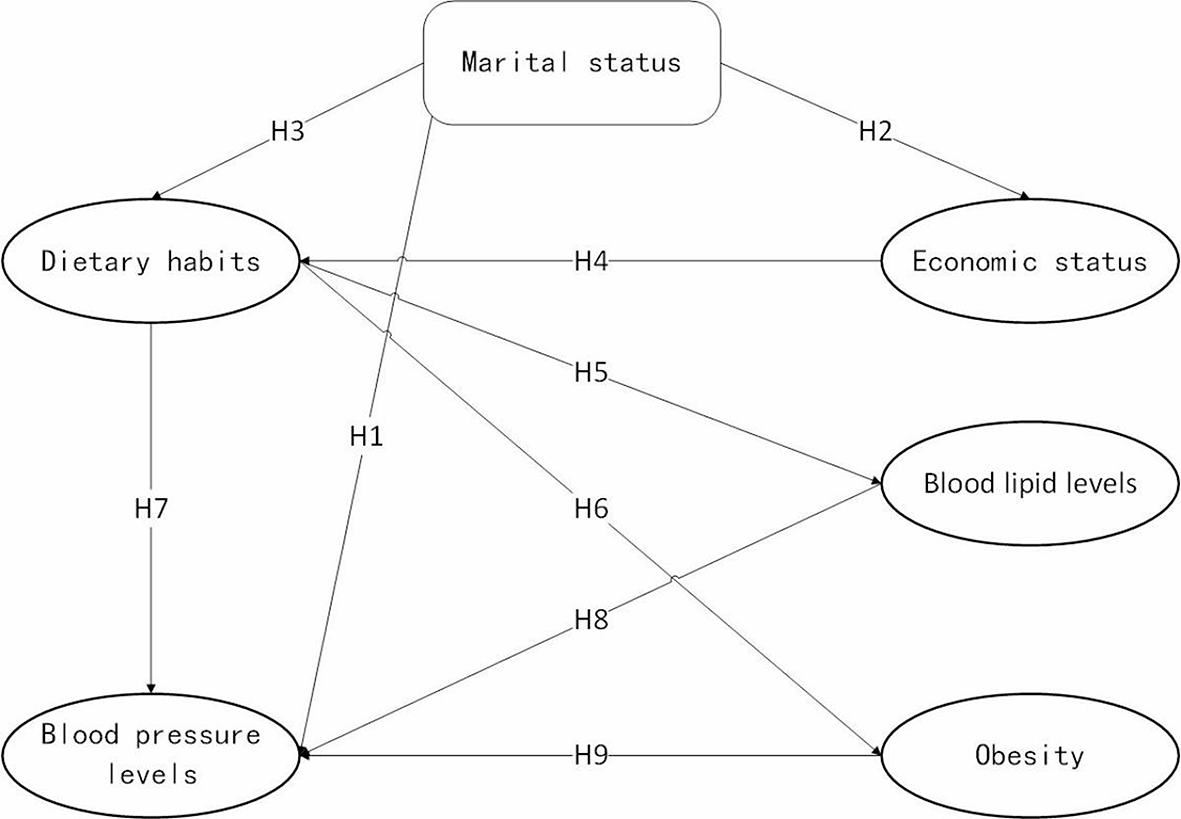

This study delves into the intricate relationship between marital status and hypertension among adults aged 20 and above in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. The findings reveal that marital status does not exert a direct influence on blood pressure levels in the male population. However, it does have an indirect impact on blood pressure levels in the female population through economic status, dietary habits, and obesity.

In the male population, marital status, whether assessed directly or indirectly, does not appear to affect blood pressure levels. This discovery contrasts with a previous study [17] which suggested that unmarried men are more susceptible to hypertension than their married counterparts. These results underscore the significance of gender-specific variations in the association between marriage and health, warranting further exploration in future research endeavors.

In the female population, marital status indirectly influences blood pressure by affecting economic status and dietary habits. This aligns with the stress-buffering model [18]which posits that social relationships, particularly marital ones, can mitigate health risks by improving socioeconomic status and lifestyle. Compared to women in stable marriages, women who have experienced marital disruption tend to exhibit higher systolic blood pressure levels. This finding is in line with prior research [17, 19,20,21] that highlights the close link between marital stability and cardiovascular health.

Moreover, recent studies [22,23,24,25] have demonstrated that individual economic circumstances significantly impact the risk of hypertension, particularly among women. This conclusion further supports the results of the structural equation model analysis in this study: marital status indirectly affects women’s blood pressure by influencing socioeconomic status. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced an additional layer of complexity to the relationship between marital status and health [26]. The data collected for this study during 2020–2023 coincided the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. The heightened social stress during this period may have amplified the advantages of marital stability and exacerbated the life stress experienced by individuals undergoing marital disruption, thereby affecting blood pressure levels.

In addition to the economic pathway identified in our structural model, previous studies have highlighted that changes in marital status—such as divorce or widowhood—can adversely affect women’s cardiovascular health through psychosocial mechanisms. Increased psychological stress, reduced social support, and heightened feelings of loneliness have been shown to contribute to elevated blood pressure and worsened cardiovascular outcomes [27, 28]. These psychosocial stressors may also lead to behavioral changes such as disrupted dietary patterns, reduced physical activity, and weight gain, thereby further compounding the risk of hypertension [29]. While our study did not directly measure these psychosocial variables, they may overlap with the observed mediating effects of economic status and lifestyle factors. Future studies incorporating direct assessments of stress, mental health status, and social support are needed to better elucidate these indirect pathways.

This study carefully examines the differential effects of marital status on blood pressure between male and female populations. The SEM final path results for males and females reveal a significant difference: the male group does not include the latent variable of economic status. Previous research indicates that in China, especially in the areas selected for this study, the financial burdens associated with marriage, including expenses related to housing, dowry, and related costs, are primarily shouldered by men [22]. This inherent economic threshold in China likely subjects’ men to an objective economic status screening before marriage. Only when a man’s overall economic status is sufficient to bear the financial pressures of forming a new family in the future can he potentially enter marriage. For women, economic status may not be a decisive factor for marriage; parents often value the wealth, work capabilities, social status, and economic prospects of a son-in-law more than those of a daughter-in-law, with chastity being particularly valued in daughters-in-law [23]. In the cultural and historical context of China, where men are traditionally expected to provide for the family while women are responsible for household chores and child-rearing [24, 30]. After a change occurs in marital status, the portion of the living expenses originally borne by men is transferred to the women themselves, while men have always been responsible for their own living expenses, it is understandable why marital stability does not significantly impact blood pressure levels in men.

Regarding the finding that economic status does not have a significant impact on dietary habits among male groups compared to female groups, on one hand, changes in marital status only have a significant impact on the economic conditions of women, thereby affecting their dietary habits.On the other hand, Alysha L. Deslippe’s psychological analysis suggests that during adolescence, females may be more influenced by external factors in their dietary habits than males [31]. In other words, the dietary habits of the female group may be influenced by events such as changes in marital status. Liu H also noted that women may be more susceptible to the psychological and physical impacts of marital stress than men [32]. These findings also provide some clues for the significance of the path between the latent variable of dietary habits among women in this study and their blood pressure status.

Finally, it is important to consider the complex interplay between sexual orientation and marital status [33] when discussing how marriage influences health. After accounting for socioeconomic status and health behaviors, the disparities in the relationship between marital status and health among individuals of different sexual orientations and genders tend to diminish.

However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations of this study. Due to its cross-sectional design, we cannot establish a causal relationship between latent variables and blood pressure. Future prospective cohort studies are necessary to validate our findings. Additionally, the small number of men in marital turmoil group (19) and the significant age distribution differences between the normal marital and marital turmoil group among women could potentially introduce bias into the study’s results. Furthermore, the study focused on permanent residents of the urban area of Baoding City, Hebei Province, China, and collected data during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. While this timing may introduce potential confounding influences, all participants were exposed to similar pandemic-related societal conditions, including public health restrictions, economic pressure, and social stress. This shared environment helps to minimize differential exposure bias between groups of different marital status. Nevertheless, due to the special nature of the pandemic period, the conclusions drawn from this study possess specific temporal and spatial specificity and may not be universally applicable. Future studies conducted outside the pandemic context are recommended to validate and extend these findings.

In summary, this study underscores the importance of considering marital status in the development of preventive and intervention strategies for hypertension. Particularly for women who have experienced marital disruption, additional social support and targeted health interventions may be warranted. These findings also suggest that strategies for hypertension prevention may need to be tailored to different gender groups.