The study is the latest to throw cold water on regular checks after the procedure.

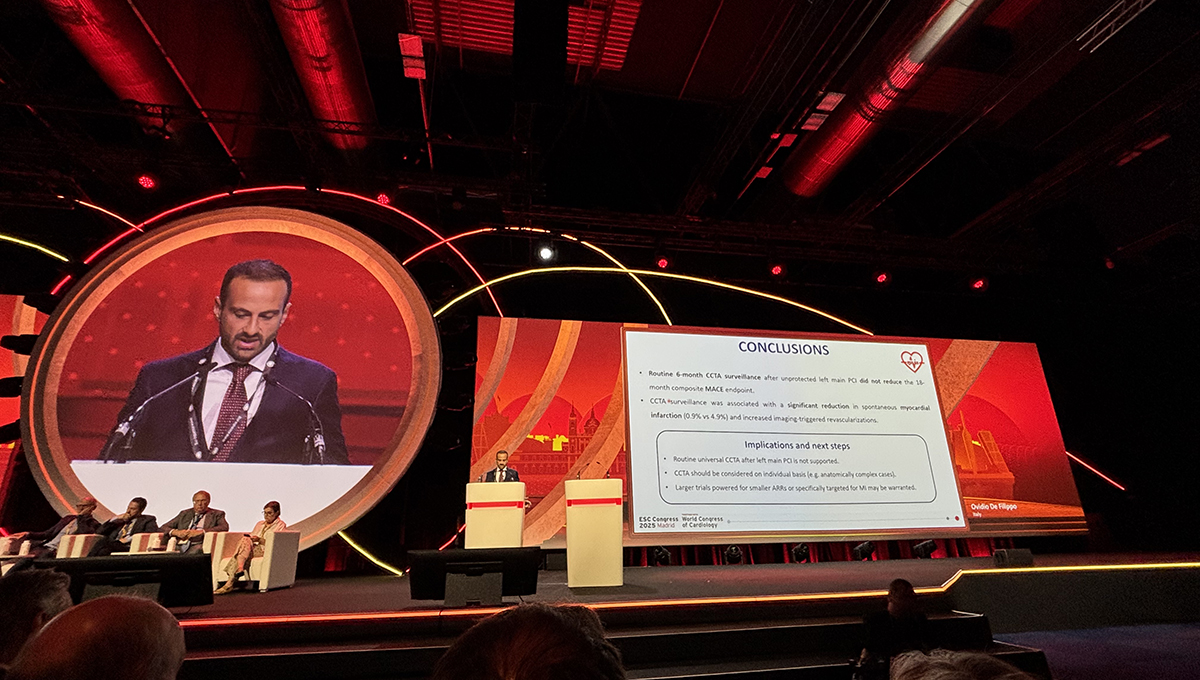

MADRID, Spain—Routine use of CT angiography after PCI for left main coronary artery disease does not lower the risk of major adverse cardiac events, results of the PULSE trial show.

The study, which was presented today during a Hot Line session at the European Society of Cardiology Congress 2025 and published simultaneously in JACC, is the latest to fail to find a benefit from regular checks after PCI, this time in a higher-risk population.

There was a signal suggesting that CT angiography performed at 6 months could lower the risk of myocardial infarction, but researchers say that finding should be considered hypothesis-generating only.

The MI finding is “provocative,” said PULSE investigator Ovidio de Filippo, MD (Citta della Salute e della Scienza Hospital, Turin, Italy), but the “routine, universal use of coronary CT angiography is not supported, [and] that is reassuring in that not all patients need an angiography even after complex PCI.” Whether such an imaging-based strategy is warranted in patients with more anatomically complex disease is still unknown, he added.

The PULSE trial stemmed from the recognition that left main PCI is still associated with a higher risk of complications and poorer long-term outcomes despite improvements in stent design and clinical care.

To TCTMD, De Filippo said the guidelines recommend relying on patient symptoms to guide post-PCI surveillance. Current European guidelines give a weak class IIb recommendation for surveillance stress testing after PCI, but the US guidelines for managing patients with ACS do not make any such provisions. For patients undergoing PCI for chronic coronary syndromes, the US guidelines advise against routine periodic testing with coronary CT angiography or stress testing if there is no change in clinical or functional status.

To date, there have been limited studies testing different surveillance strategies, including functional testing and invasive angiography, after PCI in all-comers, but none have found any benefit to routine surveillance compared with usual care. For PULSE, investigators tested the routine use of noninvasive coronary CT angiography in a higher-risk population who underwent PCI for left main disease.

‘If a Tree Is Surveilled in the Forest. . .’

In total, 606 patients (mean age 69 years; 18% female) were randomized to CT angiography-based follow-up at 6 months or to a control arm where management was guided by patient symptoms. Roughly two-thirds of patients had been admitted to the hospital for NSTE ACS, and the majority were at low-to-intermediate risk for surgery based on the SYNTAX score (mean 23). Most patients (80%) had a stenosis in the predivisional segment of the left main artery. Provisional stenting was the recommended treatment strategy, with less than 5% converted to a two-stent technique.

The primary outcome (a composite of all-cause death, spontaneous MI, unstable angina, or definite/probable stent thrombosis) at 18 months occurred in 11.9% and 12.5% of patients managed with CT angiography and usual care, respectively (P = 0.80). There was no difference in the rates of mortality or unstable angina, but MIs were less frequent in the CT angiography arm: 0.9% vs 4.9% (P = 0.004).

The rate of target lesion revascularization was not significantly different at 18 months between the two strategies, but revascularization of both target and nontarget vessels when prompted by the CT findings was higher than with usual care.

In the control arm, symptom evaluation wasn’t standardized and adherence to medical therapy was not systematically collected, which is one of the study’s limitations, said De Filippo. Also, selecting 6 months for CT angiography might be “somewhat arbitrary,” he said. While it’s enough time to detect stenosis or suboptimal PCI outcomes, he added, it’s not long enough to identify the development of neoatherosclerosis.

Gregg Stone, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), the discussant following the Hot Line presentation, likened the routine use of imaging after PCI to the old saw: If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear, does it make a sound? “Perhaps a more appropriate saying,” he suggested, “would be, ‘Should we routinely surveil the forest to look for diseased trees to prevent them from falling?’”

He highlighted the study’s small numbers, noting that it is underpowered for clinical outcomes based on projected event rates. Notably, there were just 15 MIs in the control arm and three in the surveillance group, and the big question is whether PCIs triggered by surveillance were responsible for the 12 fewer MIs.

“The primary endpoint was missed,” said Stone. “Unfortunately, and without controlling for type 1 error, the reduction in MI might be a false-positive finding. At best, that observation is hypothesis-generating. The observed 74% relative risk reduction for MI is overly optimistic. Unstable angina, stent thrombosis, and cardiovascular death were not reduced, and without a blinded 6-month CT angiography in the control arm, whether the lesions ultimately responsible for MI might have been identified at 6 months and thus treated is unknown.”

The researchers also point to several contemporary trials, chief among them ISCHEMIA, that challenge the usefulness of routine surveillance in patients stabilized after left main PCI. In ISCHEMIA, an invasive strategy that included PCI did not lower the risk of hard clinical events when compared with medical therapy.

To TCTMD, De Filippo said the group has looked into subgroups and saw a trend toward a reduced risk of MACE with CT angiography among patients with a higher SYNTAX score at baseline. “However, the numbers are very few, because they are [sent] for surgical revascularization,” he said.