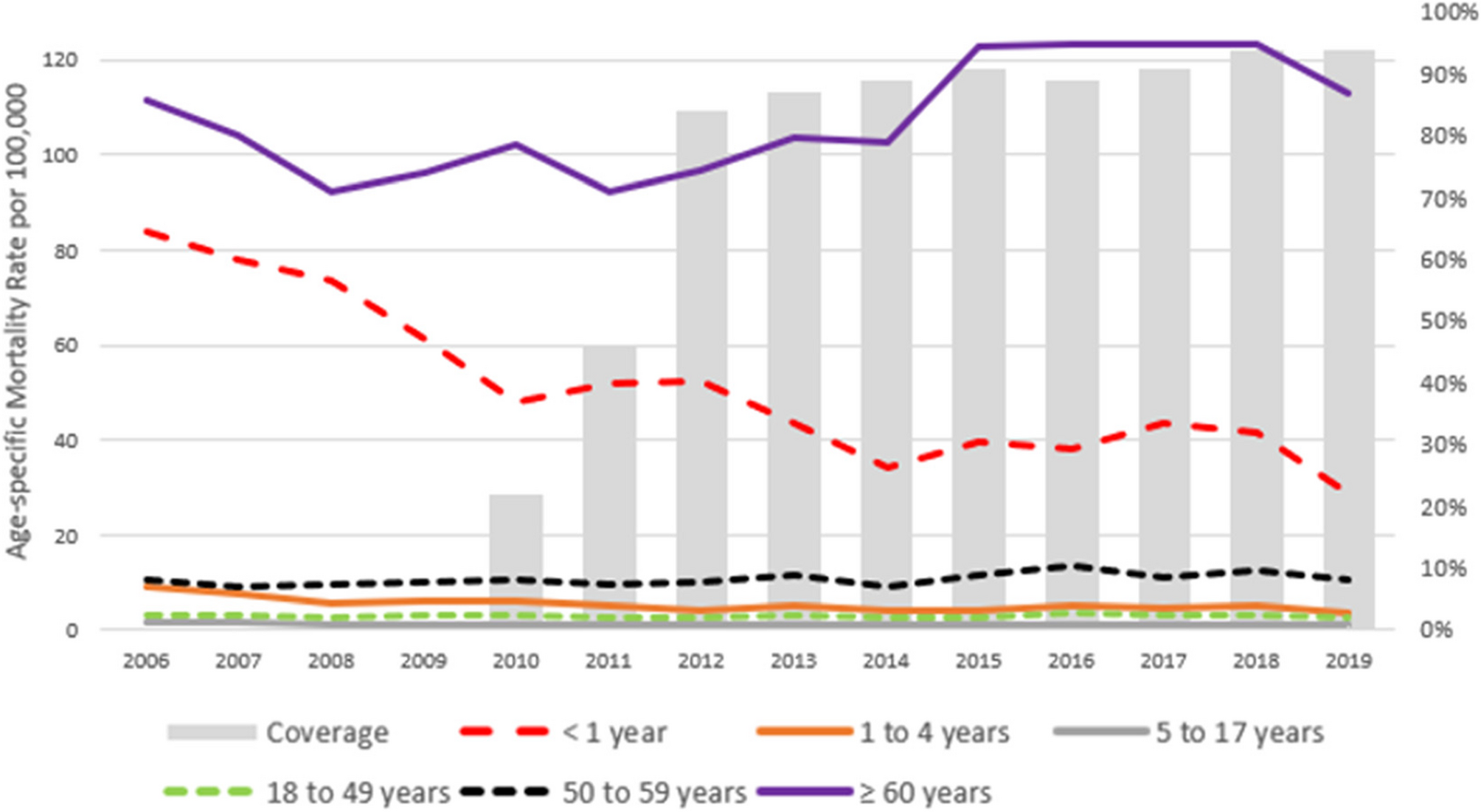

This 14-year time-series analysis, encompassing both pre-PCV10 and post-PCV10 data, provides valuable insights into the effect of pediatric pneumococcal vaccination on pneumonia mortality trends across various age groups in Colombia. Our study revealed significant reductions in age-specific pneumonia mortality rates among children under 5 years throughout the study period. Conversely, no reduction in pneumonia mortality rates was observed in unvaccinated age groups older than 5 years following the introduction of PCV10.

For infants aged < 1 year and children aged 1 to 4 years, the decreasing trend in age-specific mortality rate trends began prior to the PCV10 introduction, suggesting that factors such as the earlier implementation of PCV7 for high-risk infants and better nutrition in Colombia may have played a significant role [2, 3, 24, 25] The developing immune systems of children make them particularly vulnerable to nutritional deficiencies, which can severely impact their overall health [3]. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2016 report, childhood wasting is the leading risk factor for mortality from lower respiratory infections in children under five, accounting for 61.4% of such deaths [3]. These findings align with previous studies in Latin America, demonstrating the effect of socioeconomic improvements and introduction of PCV in preventing pneumonia-related mortality in young children [7, 25,26,27].

Unlike studies reporting reduction in pneumonia mortality in unvaccinated groups post-PCV introduction, our study did not observe this effect in individuals older than 5 years [12, 28]. These findings align with another study carried out in South American countries [17]. Interpretating our study findings in the context of serotyping data is crucial. In 2022, Colombia switched to PCV13 based on local surveillance data indicating that most pneumococcal disease cases were caused by serotypes not covered by PCV10, specifically serotypes 19 A, 3, and 6 C [18, 29]. This serotype replacement affected herd protection, as demonstrated by the increased prevalence of PCV13non PCV10 serotypes in unvaccinated older age groups in Colombia [8, 30]. Consequently, the observed effects in our study might not fully represent the broader potential for herd protection. It is essential to continue evaluating circulating serotypes, ensuring that vaccines are updated to cover the most prevalent and pathogenic serotypes. The introduction of new vaccines, such as PCV15, PCV20 and PCV21, which cover additional serotypes, might provide a more comprehensive understanding of herd protection in the future.

Our findings align with previous studies from the GBD, which reported a stable pattern of pneumonia mortality among older adults [2, 3]. This consistency highlights the often overlooked and increasing burden of pneumonia among adults aged ≥ 60 years, who accounted for more than three-quarters of pneumonia-related deaths in our study in 2019. In Colombia, older adults are defined as those aged ≥ 60 years, with this age threshold integrated into various health programs, including the vaccination schedule for older adults under the NIP, which currently offers seasonal influenza vaccine [20, 31]. Furthermore, the public health policies on Aging and Old Age for 2022–2031, supported by the World Bank, specifically target this age group [31]. Consequently, analyzing data for adults ≥ 60 years provides valuable insights for national programs, aligned with local definitions and public health policies for older adults.

Estimating the population-level effect of PCVs is challenging, particularly in low- and middle-income countries like Colombia, due to diagnostic limitations. As a result, evaluations often focus on nonspecific outcomes like pneumonia rather than pneumococcal pneumonia. In our study, only a small fraction (0.05%) of pneumonia cases were reported as J13 (pneumococcal pneumonia), making it impractical for analysis. To address this, we adopted a standard approach used by other investigators, which includes a broader range of ICD-10 codes that do not specify the causative agent but may still involve S. pneumoniae (J15-J18) [7, 17]. This approach provides a unique opportunity to understand the local pneumonia trends and assess the direct and indirect impact of PCV on pneumonia mortality.

This study has several limitations. Our evaluation specifically focused on pneumonia mortality, meaning other infectious etiologies, changes in comorbidity prevalence, or public interventions beyond the pediatric PCV in the NIP likely contributed to the reported pneumonia burden. Additionally, the lack of specific variables may hinder our ability to fully assess the impact of PCV. Although we aimed to emphasize community-acquired pneumonia, where S pneumoniae is estimated to be responsible for 38-50% of deaths across various age groups, this detailed information on community versus hospital-acquired infection was not available in the database [3, 32]. To avoid including deaths from hospital-acquired pneumonia, we adopted a methodology similar to that of the GBD 2019, considering only the underlying cause of death for pneumonia [33]. However, this approach may inadvertently include deaths related to hospital-acquired pneumonia. This limitation underscores the need for improved data collection and classification methods to accurately capture the epidemiology of pneumonia.

The strengths of our study include the use of Colombia´s national death registration data, which is categorized as high quality according to WHO standards [34]. The completeness and quality of cause-of-death assignment were maintained by Colombia’s National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), which follows stringent quality standards and conducts regular reviews and improvement plans [35, 36]. Furthermore, we analyzed data spanning a 14-year period including data, encompassing both pre-and post-PCV10 periods. The use of joinpoint regression and a permutation test involving 4,499 permutations further strengthened the reliability of our findings by rigorously testing their stability [23].

Our study findings underscore the importance of extending successful interventions, such as vaccination programs to older adults. This is particularly crucial in countries like Colombia, which are experiencing epidemiological transitions with aging populations and increased life expectancy. The data on pneumonia mortality trends across all age groups can inform national immunization policies and guide investments in interventions aimed at protecting older adults. Improving access to primary health services, including mass vaccination and preventive measures, and addressing unfavorable socioeconomic conditions are essential for controlling pneumonia among both children and older adults.