Device fabrication

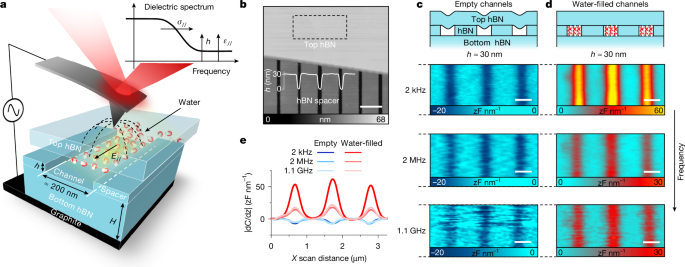

We fabricated our devices using procedures similar to those described in ref. 22. A free-standing silicon nitride (SiN) membrane was used as a substrate for our van der Waals assembly that involved four atomically flat…

We fabricated our devices using procedures similar to those described in ref. 22. A free-standing silicon nitride (SiN) membrane was used as a substrate for our van der Waals assembly that involved four atomically flat…