The research described in this article was made possible in part by federal funding awarded to Harvard Chan School scientists in the interest of protecting and promoting health for all. The future of research like this is now in question due to the government’s actions to terminate large numbers of grants and contracts and freeze funding for scientific inquiry and innovation across Harvard University.

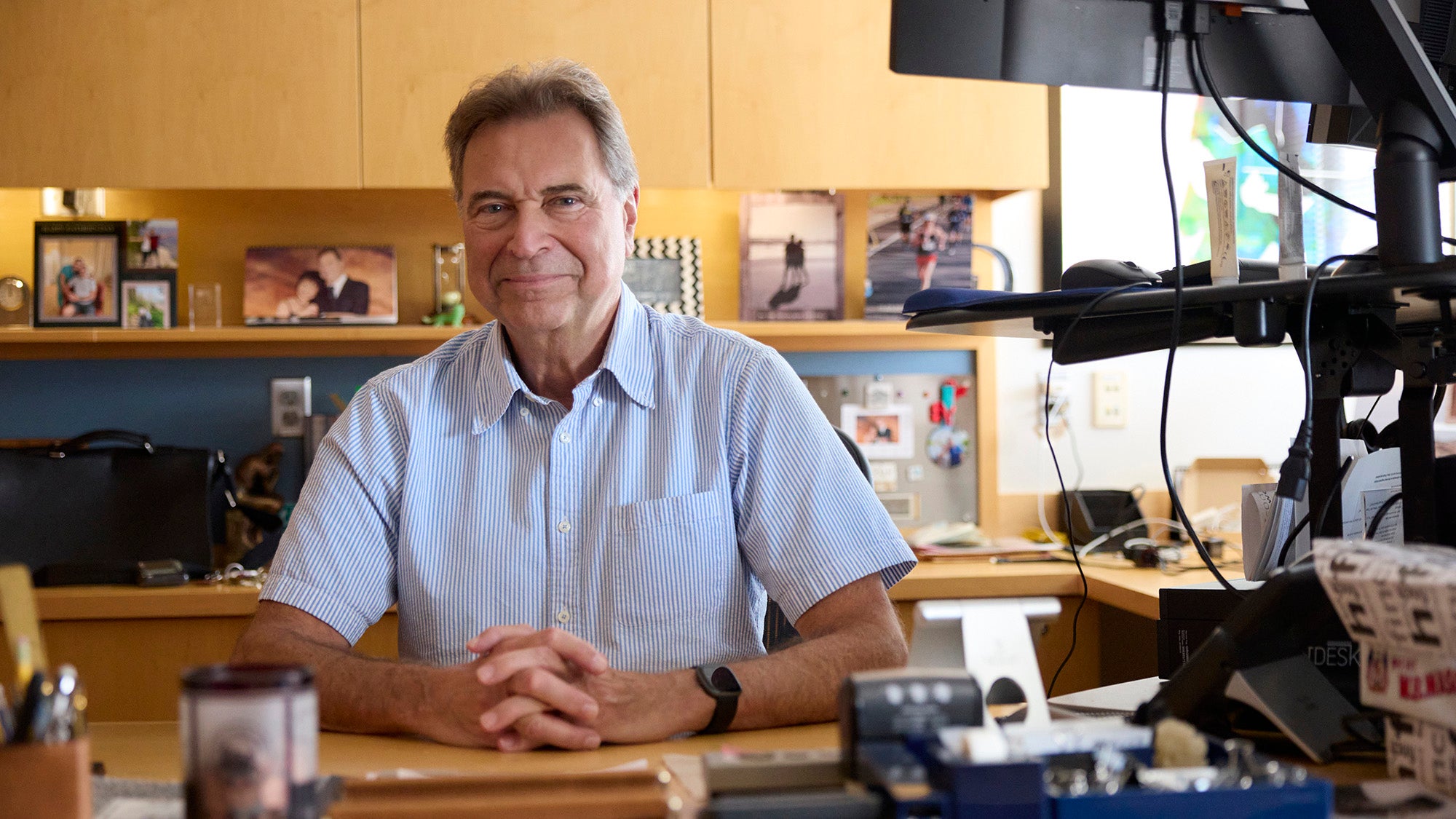

More than 30 years ago, David Christiani wanted to know why some smokers got lung cancer while others didn’t.

The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health researcher made several attempts to get a grant to answer that question from the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute (NCI)—but he was not initially successful. Part of the problem, he said, was the general assumption at that time was that if people just stopped smoking, they would lower their lung cancer risk.

“But that turns out not to be true,” said Christiani, Elkan Blout Professor of Environmental Genetics. “About half the lung cancers in the world are due to environmental exposures other than smoking. But I could not argue that at the time, because we did not have a lot of data then from developing countries and the global South. Now we do.”

Christiani eventually won NCI funding and established the Boston Lung Cancer Study (BLCS) in 1992. Since then, the BLCS has become “the longest and largest lung survival cohort in the U.S.,” according to Christiani, involving more than 14,000 patients who have been treated at Massachusetts General Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute over the past three decades. During that time, BLCS researchers have published more than 300 papers looking at which environmental and genetic factors increase the risk for lung cancer, which factors predict survival, and why some people respond to particular treatments and some do not. To conduct their studies, researchers have used a wide range of data: demographic, smoking, occupational, and dietary information; pathology reports and tumor images; information on tumor characteristics and treatments given to patients; and tumor and blood samples.

High-impact findings, but funding under threat

Among the major findings of the BLCS, Christiani and colleagues discovered in 2004 that the reason that only a small percentage of people with non-small-cell lung cancer responded well to a class of late-stage cancer drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) was because they had a particular mutation in a gene targeted by the drugs that most other patients didn’t have.

“That dramatic finding showed that you can have targeted or personalized therapy for a disease that, unless it was caught early, had a really bad outcome for decades,” Christiani said. “The five-year mortality for lung cancer used to be 14-15%; now it is about 20% for all lung cancers, and up to 26% for the most common types. That is still not great, but it is one-third better than before, and we hope it will get even better.”

The TKI study, Christiani added, highlighted the importance of well-designed population studies involving systematic data collection, the collection and proper storage of biological samples, and the use of standardized, validated questionnaires for smoking, environmental exposures, diet, and other important variables.

BLCS research has also found that exposure to secondhand smoke can lead to a higher risk of lung cancer, particularly for those who are first exposed before age 25; and that people exposed to a type of radioactivity associated with particulate air pollution have a greater risk of lung cancer recurrence and worse survival in lung cancer patients.

The federal grant that was funding BLCS was cut as part of the Trump administration’s cancellation of more than $2.6 billion in grants to Harvard University. Christiani had been expecting about $4.8 million over the next three years to support the study. Now he is not sure how he and his roughly 14-member team will keep the work going.

If the government resumes funding to Harvard, Christiani hopes to continue the BLCS and conduct research on how best to monitor for lung cancer recurrences in people who have been successfully treated. “Now that we have more successful therapies, the next question we hope BLCS can address is what is the best way to care for patients after they’ve been treated?” Christiani said. “How do you advise them and their doctors?” Overtesting, he explained, can lead to increased morbidity in patients for a number of reasons, such as unnecessary medical procedures, but undertesting could lead to a missed cancer recurrence. Said Christiani, “We want to do those outcome and survival studies to see what works best.”

Note: On Sept. 3, a federal district court judge in Boston ruled that the Trump administration’s freezing of funds intended for Harvard researchers was illegal. The administration has said it will appeal the decision, and the research funding remains frozen.