Researchers at the Hollings Cancer Center of the Medical University of South Carolina, U.S., have found that women with a history of cervical cancer have almost double the risk of developing anal cancer than women who have never had cervical cancer.

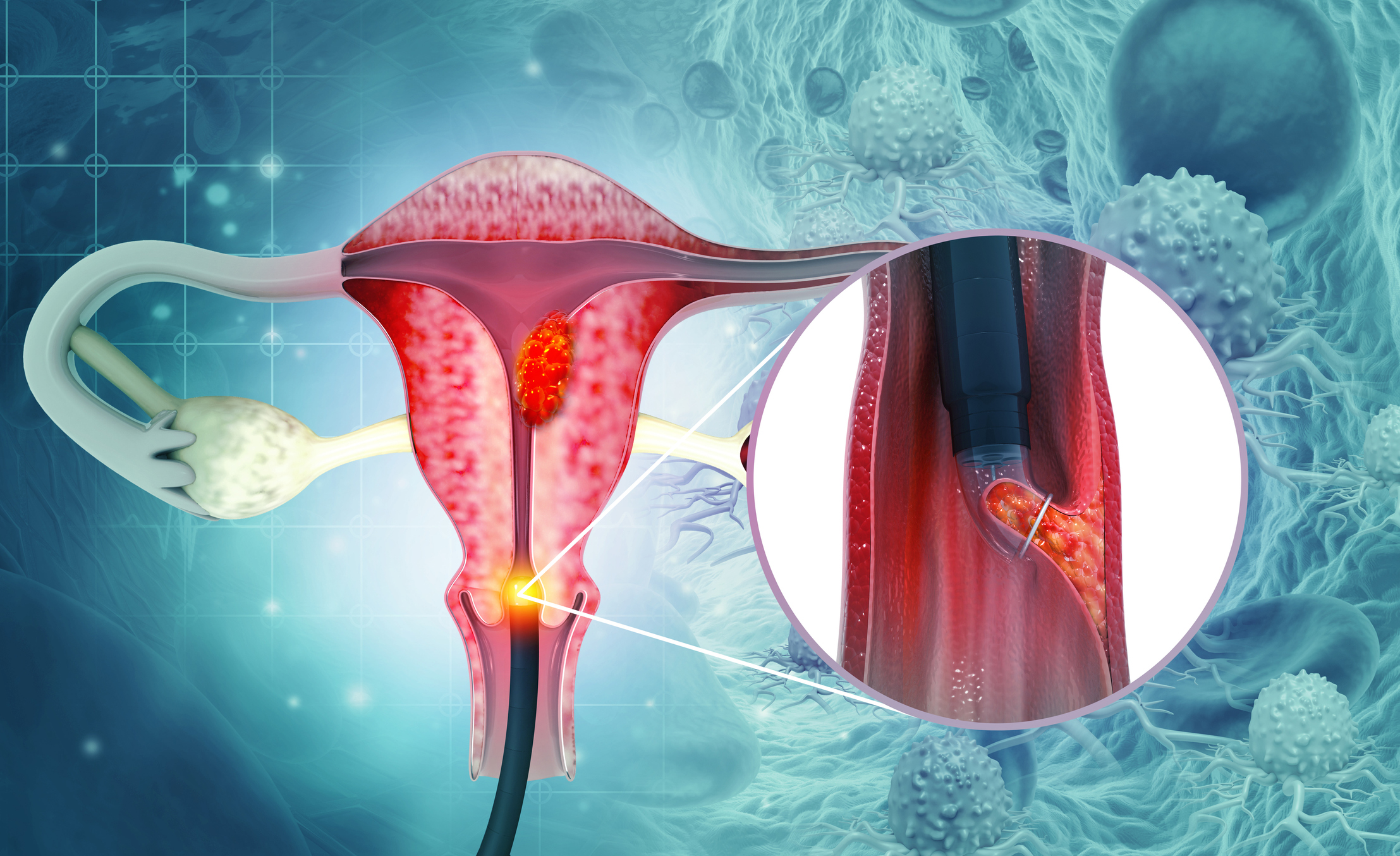

Cervical cancer mainly occurs due to an infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is transmitted during sexual intercourse. An HPV infection makes the cells lining the cervix cancerous, eventually growing into a tumor. If found early, cervical cancer has a survival rate of over 90%.

In 2022, there were over 660,000 new cervical cancer cases worldwide and approximately 350,000 deaths. While the incidence of cervical cancer has been going down in high-income countries, due to the HPV vaccination and organized screening programs, there is still a significantly high incidence and mortality rate among women from low- and middle-income countries.

What is more, there is a lack of follow-up guidelines for women who have survived cervical cancer, and a limited understanding of their risks of developing other related cancer types. Therefore, the researchers at the Hollings Cancer Center wanted to understand if women with a history of cervical cancer had a higher risk of developing anal cancer than women who had not had cervical cancer.

“We’ve known for a long time that both cervical and anal cancers are caused by HPV […],” explained co-author Ashish Deshmukh, PhD, co-Leader of the Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program at Hollings Cancer Center. “But what hasn’t been well-understood is how that shared risk might connect the two diseases over a woman’s lifetime.”

In their study, published in the journal JAMA Network Open and titled “Anal Cancer Incidence Among Women With a History of Cervical Cancer by Age and Time Since Diagnosis,” the researchers studied data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

Using this data, the team identified 85,524 women who were diagnosed with cervical cancer between 1975 and 2021. Of these women, 64 were diagnosed with anal cancer within two decades of their cervical cancer diagnosis. Compared with the general population, this meant that women who had had cervical cancer were almost twice as likely to develop anal cancer later on.

Moreover, the researchers discovered that anal cancer rates increased with age and over time. Among women younger than 45 years with a history of cervical cancer, the incidence rate of anal cancer was 2.4 per 100,000 people. Women aged 45 to 54 years had an increased incidence rate of 4.6, and women aged 55 to 64 years had an incidence rate of 10. Women aged 65 to 74 had the highest incidence rate of anal cancer at 17.6. Above the age of 75, the incidence rate went back to 10.

“Our study shows that the risk doesn’t go away—it actually increases with age and over time,” said the first author of the study, Haluk Damgacioglu, PhD, assistant professor at the Medical University of South Carolina and the Cancer Prevention and Control Research Program at Hollings Cancer Center.

The reason that anal cancer cases can occur 15 to 20 years after the cervical cancer diagnosis is that the virus causing the HPV infection can linger undetected inside the body for years or even decades, spreading to new parts of the body in the process.

“It’s a slow process, and that’s part of why it’s been so hard to detect. By the time symptoms show up, the cancer is often advanced,” explained Deshmukh.

Currently, routine anal cancer screening is only recommended for high-risk patient groups, including people living with HIV, people who have received organ transplants, or women who have had vulvar cancer.

Based on their findings, it is essential, say the researchers, that women with a history of cervical cancer be added to the high-risk group that should undergo routine anal cancer screening.

“We don’t have the resources to screen everyone,” said Deshmukh. “But we can use these data to be strategic. Screening based on risk ensures we help the people who need it most.”

In the near future, the research team wants to identify those patients who are at the highest risk of developing anal cancer after surviving cervical cancer, as well as determine screening benefits versus harms, setting the optimal age to start screening, and identifying the optimal screening intervals.

“This is about helping long-term cancer survivors protect their health,” Damgacioglu said. “They’ve already fought one cancer—we want to help prevent a second.”