Smoking helps oral bacteria settle in the gut, protecting against colitis but not Crohn’s disease. This mechanism could inspire safer treatments.

A research team led by Hiroshi Ohno at the RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences (IMS) in Japan has uncovered why smoking tobacco appears to ease symptoms in people with ulcerative colitis, a chronic condition marked by inflammation in the large intestine.

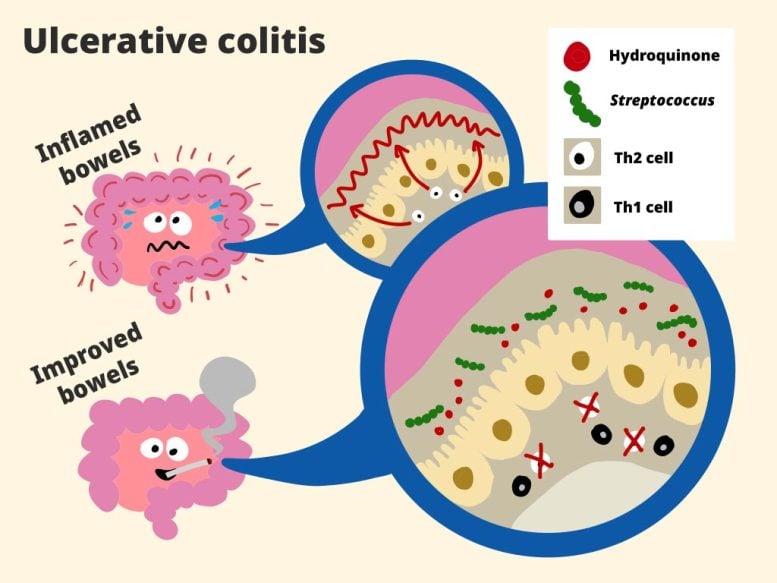

Their study, published in the journal Gut, revealed that smoking produces certain metabolites that allow oral bacteria to establish themselves in the colon, where they activate an immune response. The findings suggest that similar benefits might be achieved through alternatives such as prebiotics like hydroquinone or probiotic treatments using bacteria such as Streptococcus mitis, removing the need for smoking and its well-known health risks.

Inflammatory bowel disease exists in two main forms: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Both cause recurring abdominal pain, diarrhea, fatigue, and weight loss, but they differ in their underlying causes, the specific areas of the gut they affect, and the types of inflammation they produce.

For more than four decades, researchers have been puzzled by the paradox that smoking raises the likelihood of Crohn’s disease while at the same time offering some protection against ulcerative colitis. Because both conditions involve immune-driven inflammation in the gut, and because gut immunity is strongly shaped by the microbial community living there, Ohno and his colleagues set out to test whether the contrasting effects of smoking could be traced back to differences in gut bacteria.

Smoking changes gut bacteria

The team combined human clinical data with mouse experiments to investigate the phenomenon. In patients with ulcerative colitis, they observed that smokers had bacteria typically found in the mouth, such as Streptococcus, colonizing the gut—specifically in the colonic mucosa that lines the intestine. This was not the case for former smokers. Under normal conditions, oral bacteria swallowed with saliva pass through the digestive tract without establishing themselves, but smoking appeared to enable these microbes to take root in the gut mucosa.

The next step was to determine why. The researchers analyzed gut metabolites—small molecules generated during digestion and microbial activity. They found that smokers with ulcerative colitis had higher levels of several metabolites compared to ex-smokers with the disease. In mouse models, one of these metabolites, hydroquinone, was shown to stimulate the growth of Streptococcus in the gut lining. This suggested that smoking-related metabolites, such as hydroquinone, create conditions that allow oral bacteria to thrive in the intestinal mucus layer. But questions remained: how do these microbes reduce inflammation in colitis, and why do they not produce the same effect in Crohn’s disease?

To explore further, the team isolated 10 bacterial strains from the saliva of smokers whose oral microbes had colonized the gut mucosa. These strains were then administered to mouse models of both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis for five days. The results revealed that treatment with Streptococcus mitis produced effects nearly identical to those seen with smoking: inflammation decreased in mice with ulcerative colitis but worsened in those with Crohn’s disease.

How S. mitis affects immunity

Analysis showed that S. mitis triggered the emergence of helper Th1 cells, which are an important part of the gut’s immune response to invaders. In Crohn’s disease this likely worsens the condition because the original inflammation is actually caused by these same helper Th1 cells. But in colitis, the Th1 cells fight against an initial Th2-immune response, and this ends up reducing inflammation.

As smoking poses high risks for cancer, heart disease, and many other illnesses, it is not a sustainable treatment for ulcerative colitis. “Our results indicate the relocation of bacteria from the mouth to the gut, particularly those of the Streptococcus genus, and the subsequent immune response in the gut, is the mechanism through which smoking helps protect against the disease,” says Ohno. “Logically, direct treatment with this kind of bacteria, or indirect treatment with hydroquinone, is thus likely to mimic the beneficial effects of smoking but avoid all the negative effects.”

Reference: “Smoking affects gut immune system of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases by modulating metabolomic profiles and mucosal microbiota” by Eiji Miyauchi, Takashi Taida, Kan Uchiyama, Yumiko Nakanishi, Tamotsu Kato, Shigeo Koido, Nobuo Sasaki, Toshifumi Ohkusa, Nobuhiro Sato and Hiroshi Ohno, 25 August 2025, Gut.

DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2025-334922

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.