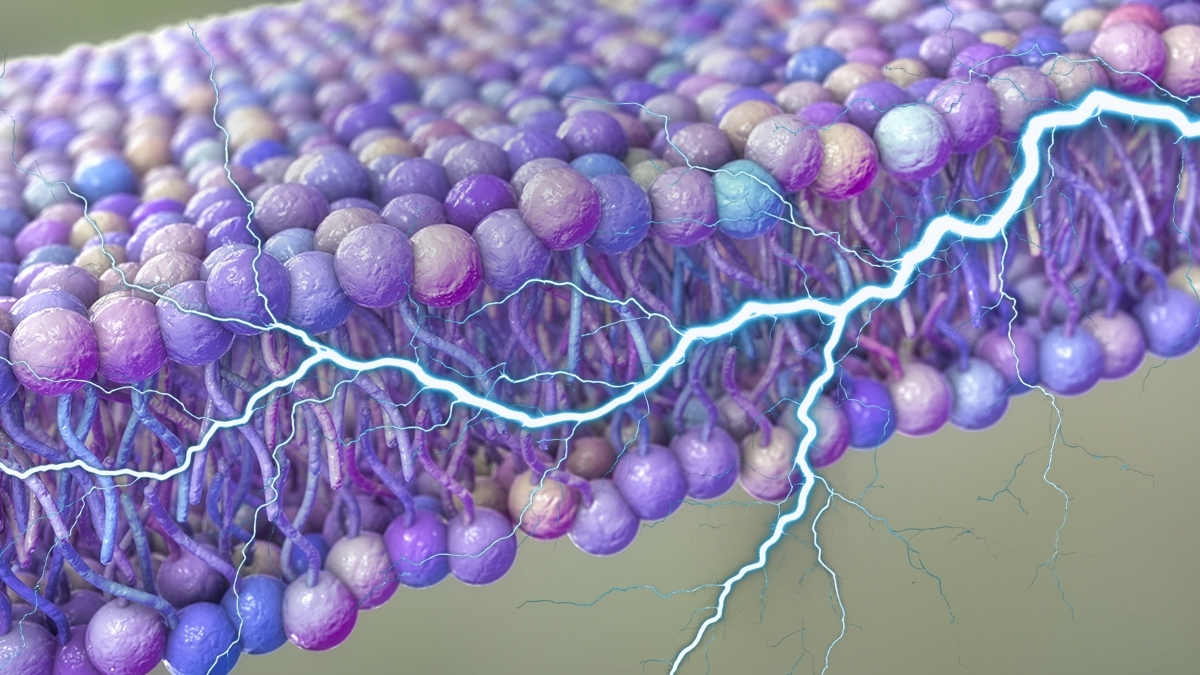

Our cells may literally ripple with electricity, acting as a hidden power supply that could help transport materials or even play a role in our body’s communication.

Researchers from the University of Houston and Rutgers University in the US…

Our cells may literally ripple with electricity, acting as a hidden power supply that could help transport materials or even play a role in our body’s communication.

Researchers from the University of Houston and Rutgers University in the US…