Why you may feel side effects

The training process is what causes common vaccine side effects such as a sore arm, fatigue, mild fever and chills, though it’s important to note that not everyone experiences side effects after vaccination.

“If I feel that way after the vaccine, I know I’ve gotten something. I know my immune system is responding,” Hopkins says.

The temporary inflammation your body creates is part of building protection. These effects usually last only a day or two and are far milder than what you’d experience with the actual infection.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says serious adverse reactions can happen after vaccination, but are rare. If you have concerns about side effects or adverse reactions, talk to your doctor, who can help explain the risks vs. benefits of vaccines.

Why do some vaccines last longer than others?

Some vaccines protect you for a lifetime, while others need a booster or require a new shot every year. The difference comes down to the nature of each virus, Schaffner says.

Measles, for example, is a very stable virus, he says: “Measles is basically the same virus that infects children now around the world as it was 50 years ago.” (AARP: Do you need a measles vaccine?)

That makes it easy for your immune system’s memory cells to recognize it year after year.

Also, measles takes nearly two weeks to make you sick, Schaffner says, giving your body plenty of time to fire up its defenses and shut it down in the bloodstream.

Viruses like flu and COVID-19 are different. They change, or mutate, frequently, and newer variants may not be as susceptible to previous vaccines or immunity.

What’s more, these viruses replicate right on the surface of your nose and throat — places where antibodies don’t work as well. That’s why flu and COVID-19 vaccines may not always prevent the sniffles and coughs of a mild infection, Schaffner says, but they’re very good at keeping you out of the hospital.

What is herd immunity and why is it important?

The more contagious a virus is, the higher the percentage of people who need to be vaccinated to stop its spread, Schaffner says.

Measles, for example, is one of the most contagious viruses, so about 95 percent of people in the community need to be vaccinated to stop its spread.

That matters because some people can’t get vaccines at all or their immune systems don’t respond fully. If everyone else gets vaccinated, it provides “a cocoon of protection” around them, Schaffner explains.

That’s the idea behind herd immunity, he says. “Vaccines protect the individual being vaccinated, but that’s half of what they do. The other half of what vaccines do is that they protect the entire community.”

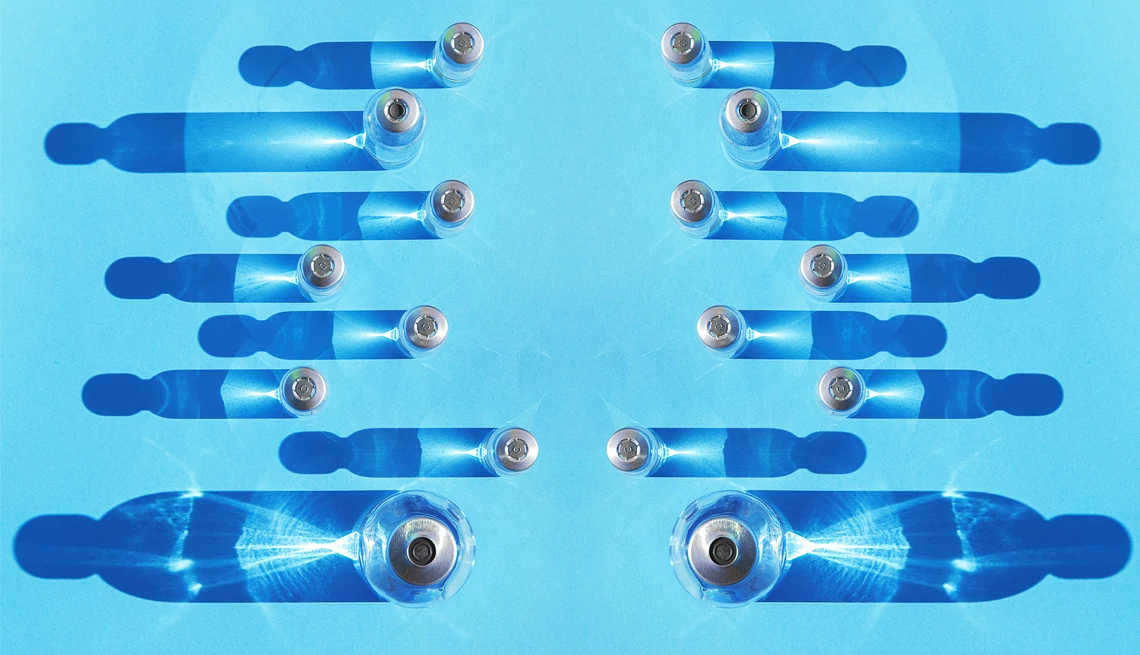

Cuts in mRNA research

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recently announced that it is decreasing funding for the development of mRNA vaccines, citing concerns over safety and efficacy. These vaccines are best known for their role in fighting COVID-19, but are also being studied for the treatment of diseases like cancer and HIV.

Many researchers and public health experts say the cuts are a major scientific setback. Five leading physicians’ groups, including the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in a statement that they are “dismayed and alarmed” by the decision.

“This act stifles scientific innovation and our country’s ability to react swiftly to future pandemics and public health emergencies — putting millions of lives at risk,” the statement said.

“Sustained research funding is essential to developing the next generation of tools that protect Americans from infectious disease. Thanks to decades of rigorous science, testing and monitoring systems, vaccines used in the U.S. continue to be safe, effective and save lives.”