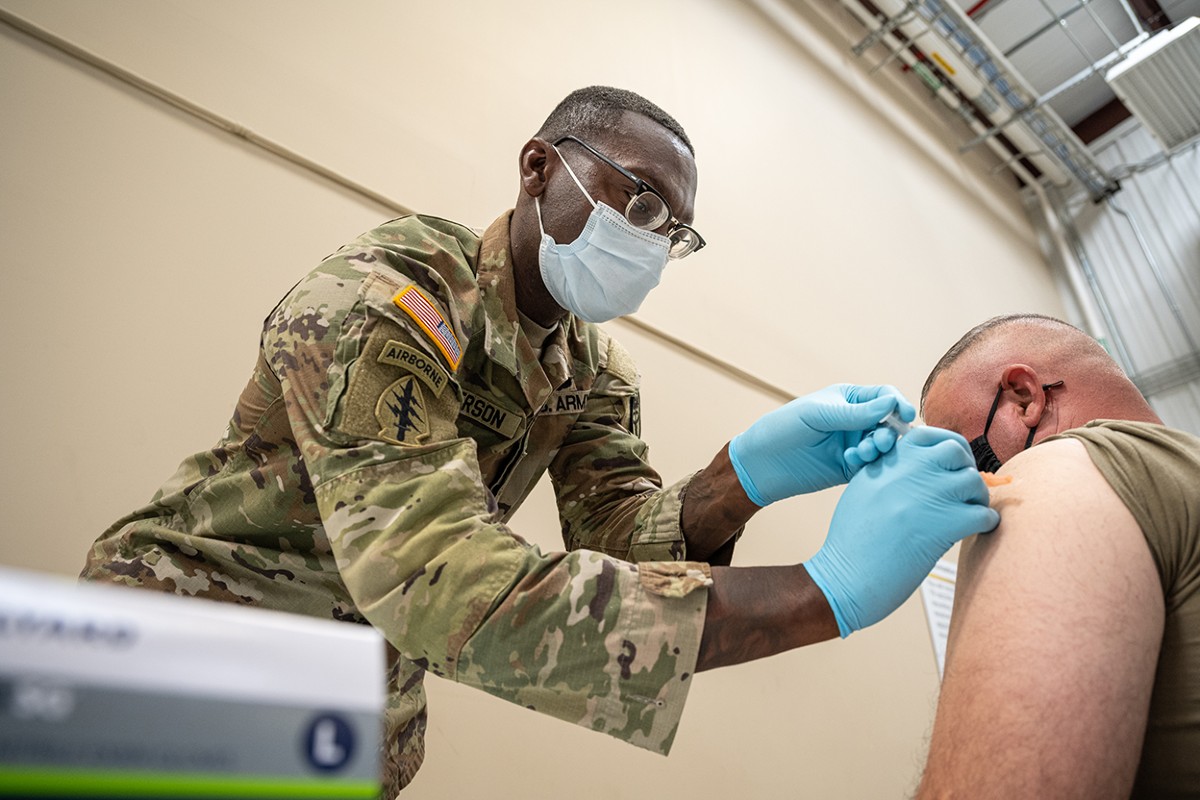

The US government invests in vaccine development to, in part, protect soldiers from dangerous pathogens in various parts of the world.Credit: Jon Cherry/Getty

The abrupt termination last month of nearly half a billion dollars in US government contracts for mRNA-vaccine research rattled scientists working inside and outside industry. The cuts raised alarm about the country’s commitment to the Nobel-prizewinning technology, which is credited with saving millions of lives during the COVID-19 pandemic and is regarded as essential for fighting viruses in the future.

How political attacks could crush the mRNA vaccine revolution

Yet not all large-scale research into mRNA vaccines in the United States is being dismantled. Nature has learnt that, even as the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) — led by vaccine critic Robert F. Kennedy Jr — pulls back, the country’s military continues to bankroll parts of the same research.

Among the beneficiaries are programmes developing vaccines against some of the world’s deadliest pathogens, including the virus that causes Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF), a tick-borne disease that kills up to 40% of those infected. In the United States, the government considers such research crucial not only because these pathogens threaten soldiers deployed abroad, but also because they could ignite a global outbreak.

“A lot of us are at least relieved the Department of Defense [DoD] is not abandoning mRNA research,” says Amesh Adalja, an infectious-disease specialist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, Maryland.

Still, he cautions that the HHS’s rejection of the technology, combined with broader policy fractures across the government, threatens to hobble national — and global — readiness for emerging infectious threats.

“The whole biodefence structure is completely derailed,” Adalja says. “I’ve never seen it be disconnected like this.”

Turbulent times

Peter Berglund learnt that his company’s federally backed vaccine programme was being cut the same way that many other affected firms did — in a 5 August notice from the HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), which ordered an immediate shutdown of ongoing studies. For Berglund, chief scientific officer at HDT Bio in Seattle, Washington, the news was a gut punch, as he told colleagues at a conference on RNA-based therapeutics in Boston, Massachusetts, this month.

NIH has cut one mRNA-vaccine grant. Will more follow?

HDT had been developing a next-generation CCHF vaccine based on a form of RNA that can copy itself inside cells. The company had secured tens of millions of dollars in federal contracts, which it used first to test a shot in mice1 and monkeys2, and then to begin a human trial in Texas this July. The BARDA memo brought everything to a halt the very next month.

But “that was mommy”, Berglund says. “Then daddy calls.”

Within days, HDT executives heard from project managers at the DoD’s Joint Program Executive Office (JPEO) for Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Defense, which had been co-funding the CCHF vaccine research. HDT was told to restart its trial, with the JPEO pledging support through at least this first phase of clinical evaluation.

“It’s been so turbulent,” Berglund says. The DoD funding, although substantial, is less than what had originally been pledged in conjunction with BARDA. “But, at least now, we can advance it through phase I” and worry about the rest later, he adds.

A ‘restructuring’ of resources

Others with projects co-funded by the JPEO also learnt of funding cuts and a “restructuring of collaborations” in the 5 August notice. But their situation is less clear.

Earlier this month, AstraZeneca, a pharmaceutical company headquartered in Cambridge, UK, began a human trial of two mRNA vaccines, despite the notice. Each is designed to protect against a different strain of avian influenza. Clinical-trial registries still list both BARDA and the JPEO as collaborators.

An AstraZeneca spokesperson declined to comment on the US government’s role in funding the trial against bird flu — which has been infecting US poultry and dairy cattle and raising the spectre of a leap into humans. The JPEO did not respond to requests for comment.

In a statement, HHS press secretary Emily Hilliard disputed suggestions that withdrawing from joint projects would weaken the nation’s pandemic preparedness, writing that “BARDA is prioritizing evidence-based, ethically grounded solutions”.

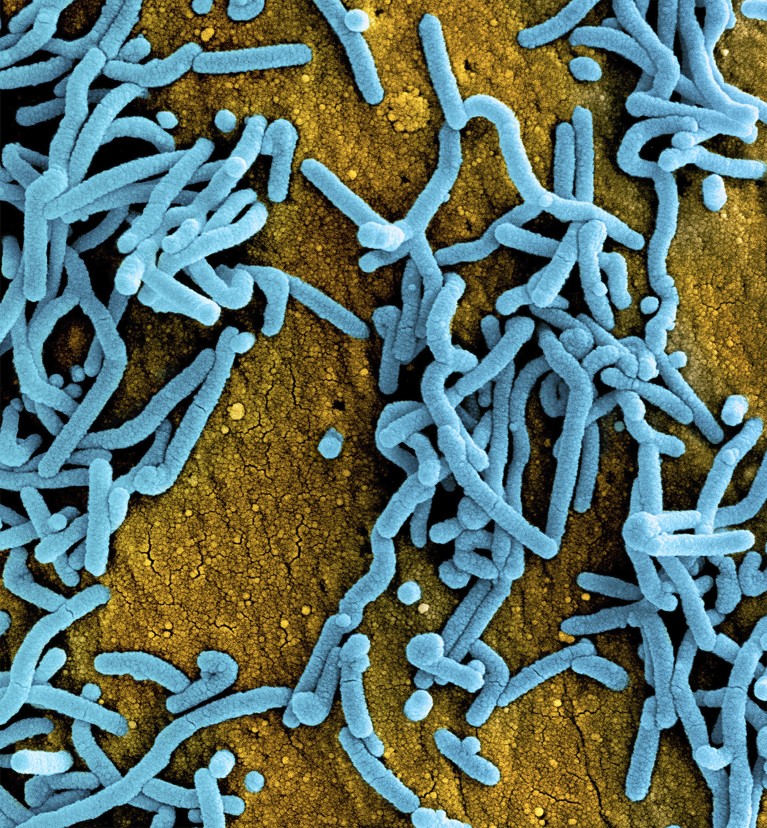

Like its relative Ebola, Marburg virus can also cause haemorrhagic fever.Credit: NIAID/Science Photo Library

The JPEO and BARDA had also been jointly funding a preclinical-stage vaccine programme for biotechnology firm Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts3. The mRNA shot is aimed at Marburg virus — a close but even deadlier relative of Ebola — which caused an outbreak earlier this year in northwest Tanzania, resulting in ten deaths. Neither Moderna nor its collaborator, the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, responded to e-mails from Nature seeking comment on the project’s funding status.