This research explored the heterogeneity of depressive symptoms in older patients with chronic diseases through the ten dimensions of the CES-D scale. An individual-centered approach was used in this research to identify subtypes of depressive symptoms in older patients with chronic diseases. Some of the entries in social support can have an impact on depressive symptoms in older patients with chronic diseases. The details are discussed below.

Latent profiling of depressive symptoms in older patients with chronic diseases

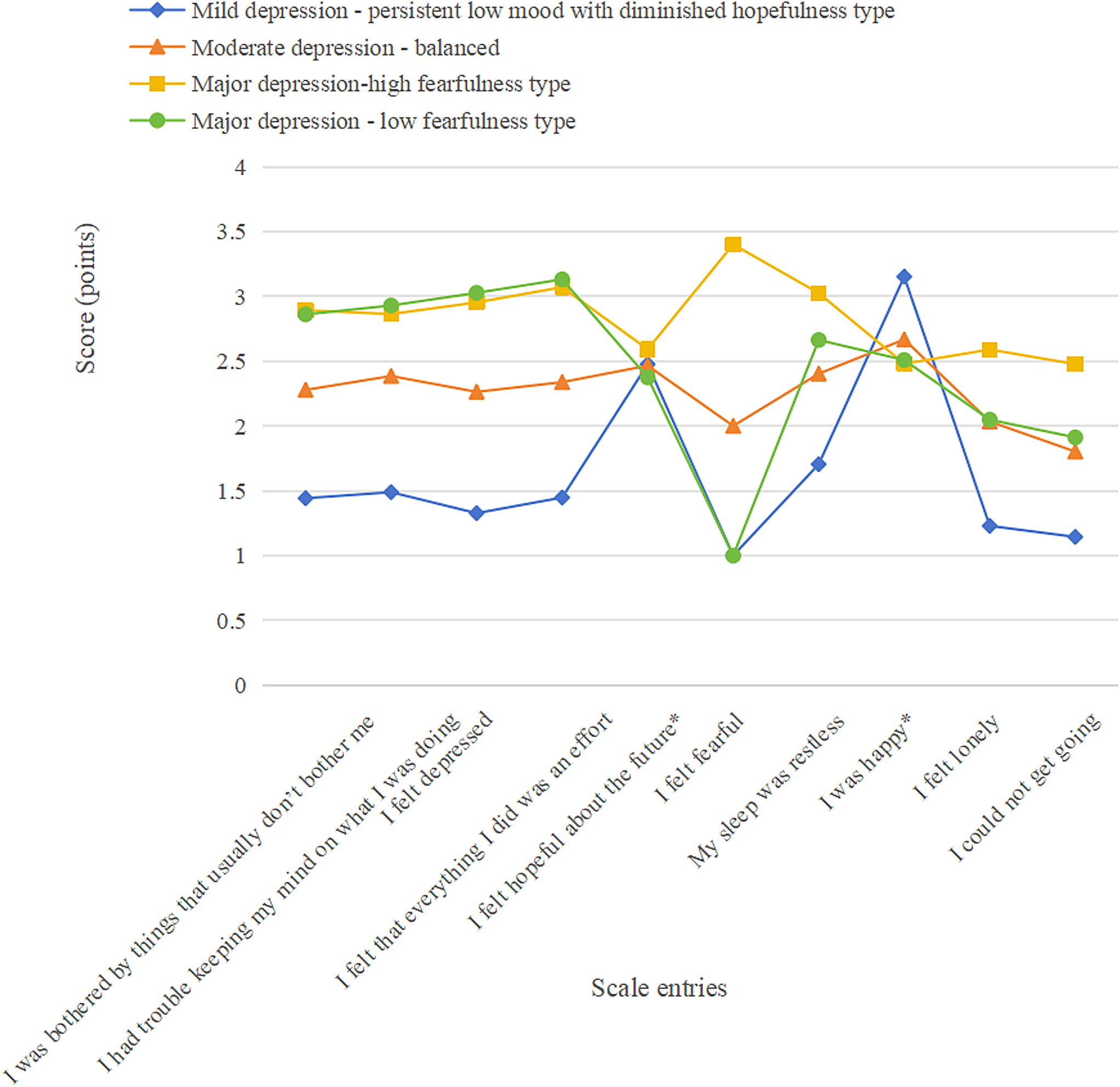

We used latent profile analysis to categorize depressive symptoms in older patients with chronic disease. The results showed that the depressive symptom scores of older patients with chronic diseases had distinct categorical features and could be categorized into four potential categories: mild depression, moderate depression, major depression(high fearfulness), and major depression(low fearfulness). The fit indices showed that the model fit well, indicating that there were differences between the potential categories of depressive symptoms in older patients with chronic diseases, reflecting the heterogeneity of depressive symptoms in this group. According to the scale scoring results, patients with mild depression exhibited elevated scores on the reverse-scored items ‘I felt hopeful about the future’ and ‘I was happy.’ This pattern aligns with their symptomatic presentation of chronic emotional distress and loss of hope in daily life. The moderately depressed-balanced type accounted for 7.95% of elderly patients with chronic diseases, representing a relatively low proportion. This subtype is characterized by comprehensive depressive manifestations, with relatively balanced severity across various depression-related symptoms (e.g., low mood, anhedonia, anxiety), without predominant emphasis on any specific emotional dimension. Whereas the major depression(high fearfulness), the major depression(low fearfulness) moved more consistently across all items, except for the entry ‘I feel fearful,’ where scores varied considerably. Fear is prevalent among older adults, particularly those with chronic conditions, and frequently manifests as fear of falling and fear of death [23, 24]. Such emotional states not only exacerbate patients’ psychological burden but may also adversely impact health status through behavioral feedback mechanisms. For instance, excessive fear of falling may lead to intentional reduction of daily activities [25], ultimately resulting in diminished quality of life and creating a vicious cycle of ‘fear – activity restriction – functional decline – increased fear’.

The refined classification and characteristic analysis of four latent depression subtypes among older adults with chronic diseases provides clinically actionable guidance for targeted health management. For patients with the mild depression, whose distinctive high scores on reverse-coded items like ‘I felt hopeful about the future’ and ‘I was happy’ were observed, clinical interventions should emphasize hope-building and positive affect enhancement through tailored psychological counseling to restore positive life expectations.Patients exhibiting the moderate depression require comprehensive intervention strategies addressing multiple dimensions including emotion regulation, interest stimulation, and anxiety reduction, necessitating integrated psychological approaches to holistically improve depressive symptoms. Regarding the two severe depression subtypes, their differential manifestation primarily in “I feel fearful” items warrants distinct fear-focused interventions: for the high-fear type, prioritized fear management (particularly addressing fall-related and death anxiety) through fall prevention training and death education could break the vicious cycle of “fear-activity restriction-functional decline-worsened fear”; whereas for the low-fear type, while maintaining standard severe depression interventions, clinicians should investigate potential underlying psychological issues not masked by fear responses to ensure intervention precision.

This subtype-specific intervention paradigm effectively addresses depression heterogeneity in older chronic disease patients, enhances psychological intervention efficacy, improves quality of life, and ultimately reduces health burdens. The approach demonstrates significant practical utility for clinical practice and health management.

The effect of social support on a subgroup of depressive symptoms in older adults with chronic disease

Social support is the recognition and assistance individuals feel originates from society and can buffer life’s stresses and promote healthy outcomes [26]. Social support is an essential protective factor for mental health status, i.e., the higher the level of support received from family, friends, and medical staff, the lower the level of psychological distress in older patients with chronic disease [27].

The present research showed that patients with a lower number of social engagement activities were more likely to be in the major depression group, which is consistent with previous studies [28,29,30,31,32]. For older people with chronic disease, the impact of social support through participation in group leisure activities on the quality of life increases as their chronic conditions worsen over time. This is because participation in social activities not only provides older patients with chronic diseases with a greater sense of social participation but also strengthens the immunity of older patients with chronic diseases against chronic diseases through physical exercise, thus providing a buffering effect and reducing the negative impact of chronic diseases on their quality of life [33]. The activity type may have different effects on people’s health and functioning, e.g., Hong S I suggests that engaging in more volunteering and healthy exercise can significantly affect longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms [34]. Such hypotheses are also supported by subsequent relevant studies [35, 36]. However, Simone Croezen [37] showed that participation in religious activities was the only form of social engagement associated with reduced depressive symptoms. Conversely, participation in political or community organizations was associated with increased depressive symptoms. However, Wanchai’s review of the relevant English language literature from 2006 to 2016 indicates that social participation significantly benefits older people’s health and encourages society to create a favourable environment conducive to older people’s participation in group and individual activities [38]. There is no uniformity between the results of different studies, and older people with chronic disease should be offered social activities of interest to them, depending on their specific situation.

This study revealed that compared to individuals with mild depression, those receiving financial support from their children in the range of 30,000 to 40,000 RMB exhibited a significantly higher probability of progressing to moderate depression and major depression(low fearfulness). This finding suggests that the significant association between financial support from children and depression classification exists only within a specific income range. Considering the limited existing research evidence, we tentatively propose the following interpretation: The relationship between financial support from children and depression among older adults is not driven by a single factor, but rather results from the complex interplay of multiple variables. Specifically, factors such as the elderly’s pre-existing financial reserves, cognitive biases arising from “mismatches between expectations and reality,” a potential “threshold effect” among middle-income groups, and the coverage level of healthcare policies may all play moderating roles [39, 40]. The combined effect of these factors may lead to a nonlinear relationship that demonstrates statistical significance only within specific ranges of financial support. Furthermore, these interacting factors may obscure or distort the underlying association pattern, resulting in only weak significance within particular intervals. Additionally, limitations in sample representativeness might have influenced the results, as the study sample did not adequately cover older adult populations from diverse socioeconomic, cultural, and regional backgrounds, which somewhat reduces the generalizability of the findings. Based on this analysis, future research should further optimize the study design, improve the variable measurement system, and expand the sample coverage to enable a more thorough and accurate investigation of the intrinsic relationship between financial support from children and depression among older adults.

Compared to the moderate depression, those who did not participate in pension insurance were more likely to favour the major depression(low fearfulness), which was 1.5 times more likely than those who participated in at least one type of pension insurance. This finding is consistent with previous research [41]. However, there is another argument that health insurance and pension insurance can, to a certain extent, increase the level of life satisfaction of the older [42], which, in turn, affects the psychological condition of the patients [43, 44]. The main purpose of pension insurance is to provide income in old age; alleviating depressive symptoms may only be a “by-product” of being a pensioner who can contribute to improving mental health through at least three channels: labour supply, family relationships, and consumer spending [41].

The stress-buffering effect of social support demonstrates significant differential characteristics across depression subtypes in elderly patients with chronic diseases. Research reveals that higher levels of social support are associated with marked reductions in negative emotions within this population, with this association being particularly pronounced among individuals exhibiting mild depressive symptoms—enhanced social support effectively alleviates their psychological distress, including low mood and anxiety.

It should be emphasized that certain social support variables showed no significant correlation with depressive symptoms. This finding should not be dismissed as a mere “negative result,” but rather highlights the complexity of psychological mechanisms in elderly chronic disease patients: the development and alleviation of depressive symptoms may involve interactive effects among multiple factors, including dimensions of social support, disease characteristics, and individual psychological traits. Relying solely on a single type of support or a uniform support model may fail to meet the needs of all subgroups.This discovery of differential associations carries important practical implications: it indicates that social support is a key modifiable factor in improving the mental health of elderly chronic disease patients [45]. Accordingly, community health workers should implement interventions from two perspectives. First, they should actively guide patients in establishing family support systems by encouraging family members to strengthen emotional companionship and address psychological needs, ensuring elderly patients consistently perceive care and support from their surroundings—particularly for those with mild depression, where timely and targeted support is crucial. Second, community health service centers should enhance complementary health services, such as chronic disease health education to improve patients’ disease awareness and coping skills, and optimize specialized health check-ups for the elderly to reduce anxiety stemming from insufficient health information. Through systematic assistance, these measures can effectively fortify mental health safeguards for elderly chronic disease patients [33].

Effects of other influences on depressive symptom subgroups in older adults with chronic diseases

The present research shows that females are more skewed towards moderate depression, major depression(high fearfulness) and major depression(low fearfulness). This phenomenon may be attributed to multiple factors: women typically shoulder greater responsibilities and burdens in both social and family domains; with advancing age, they gradually withdraw from the workforce while experiencing reduced social and recreational activities; furthermore, their emotional processing tends to be more nuanced and sensitive – all of which collectively contribute to women’s heightened emotional vulnerability compared to men [46, 47]. Additionally, Physiological stress response differences may also increase susceptibility [48], though these mechanisms remain debated.

The lower the number of chronic disease, the more likely they are to be in the mild depression. Older adults with chronic physical disease and the persistence of chronic disease can cause or exacerbate psychiatric symptoms to some extent [49]. Older adults with multimorbidity often experience functional decline and reduced daily activity capacity. Moreover, persistent disease not only compromises quality of life but also leads to sleep disturbances, impaired concentration, and social participation difficulties, potentially triggering anxiety and depression [33]. The chronicity of these conditions may foster fears of disease progression and uncontrolled deterioration, exacerbating psychological distress [33]. Effective management of physical illnesses in older adults could therefore alleviate both physical and mental health burdens.

Compared to the mild depression, unmarried people were more likely to be in the major depression(high fearfulness) and major depression(low fearfulness), which were 1.445 and 1.323 times more likely than married people, respectively. This research refers to unmarried, including widowed, divorced, separated, and never married. Spousal support may buffer against depression through mutual comfort during adverse events [50]. Without such support, unmarried older adults often experience loneliness, reduced life satisfaction, and increased anxiety/depression risk due to inadequate psychosocial support [51].

Individuals with lower educational attainment exhibit a higher likelihood of falling into the moderate-to-severe depression category. This may be related to education enhancing an individual’s cognitive abilities, including problem-solving skills, critical thinking, etc. The enhancement of these abilities helps individuals to better cope with life’s challenges and difficulties and reduces depression [52, 53]. This research also showed that the lower the life satisfaction, the more likely you are to be in the major depression group. This likely reflects cumulative negative impacts from multiple factors, where limited social engagement fails to adequately mitigate depressive symptoms [50].

The present research also showed that people who drank alcohol were more likely to favour the major depression(high fearfulness). Chronic heavy drinking may trigger mood changes, aggression, attention, and productivity deficits, including relationship, work, and financial instability, which in turn may trigger negative mood and depressive symptoms [54, 55]. Enzymes involved in the metabolism of folic acid may be affected by prolonged heavy drinking, which in turn may lead to depressive symptoms, and sleep patterns disrupted by alcohol consumption may also underlie the development of depression [56, 57].

Interestingly, our study revealed that compared to mild depression, elderly individuals aged below 80 years were more likely to develop major depression(high fearfulness) than those aged above 80 years. This difference can be reasonably explained by the relatively preserved neural structures (e.g., prefrontal cortex, amygdala) in younger elderly individuals, which maintain more sensitive emotional response mechanisms to negative stimuli. In contrast, older age groups exhibit elevated emotional regulation thresholds due to neurodegenerative changes [58]. Moreover, advanced-age elderly often present with multiple chronic conditions, where somatic suffering may replace or mask emotional fear. Conversely, younger elderly with relatively preserved physical function demonstrate more distinct fears about “potential future disability/illness,” which tend to compound with depressive symptoms [59, 60]. However, current evidence remains insufficient regarding optimal age stratification for these observations. Individuals with limitations in activities of daily living and poorer self-rated health demonstrated significantly higher susceptibility to moderate-to-severe depression compared to those with mild depressive symptoms, reflecting multifaceted underlying mechanisms. Restricted physical activity may disrupt normal neurotransmitter secretion, interfering with their synthesis and transmission, thereby contributing to depressed mood and increased depression risk [61]. In our current analysis, we dichotomized physical activity limitation as present or absent, which might obscure potential gradient effects of ADL disability severity on study outcomes. This factor warrants further stratified analysis in subsequent research. Those with poorer self-rated health likely experience greater chronic disease burden, exacerbating physical and psychological stress. Furthermore, this population often exhibits excessive health-related anxiety, and this persistent anxious state may impair normal psychological regulation processes.