When several countries endorsed the notion of some high-risk people taking the antibiotic doxycycline after unprotected sex to lower their chances of contracting a sexually transmitted disease, as the U.S. did last year, there was a theoretical concern the shift could drive antibiotic resistance in some bacterial infections.

That risk no longer appears to be theoretical.

In a newly published letter in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers reported a steep rise in resistance to tetracycline — the antibiotic class to which doxycycline belongs — in gonorrhea isolates collected from across the country since results of the studies investigating the use of so-called doxy PEP were made public. PEP is short for post-exposure prophylaxis.

An earlier report out of the University of Washington showed a similar trend in the Pacific Northwest, as well as a rise in tetracycline resistance in other bacteria carried by people who took doxy PEP, specifically Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus.

Yonatan Grad, senior author of the latest report, said there is a clear benefit in advising some people at high risk of contracting an STI to take a dose of doxycycline within 72 hours of having unprotected sex. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends health care providers discuss the pros and cons of using doxy PEP with all gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men, and transgender women who have had a bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the last year.

But Grad said the benefit is mainly for controlling chlamydia and syphilis, and for driving down rates of congenital syphilis, which can trigger stillbirths, miscarriages, and can result in devastating birth defects for babies born with the infection.

Evidence is growing, however, that the benefits of doxy PEP come with a cost: increasing resistance in other bacterial pathogens, said Grad, a professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“It’s less a theoretical concern now and more [that] we have evidence to indicate that it’s happening,” said Grad, whose co-authors are from Harvard and the College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Georgia, in Athens.

Several studies found that using a single dose of doxycycline within 72 hours of unprotected sex to fend off STIs had a dramatic effect on lowering rates of infections. Chlamydia and syphilis cases declined by nearly 80%, and gonorrhea infections dropped by about 50%. The benefit for gonorrhea will likely decline as resistant strains of the bacterium continue to spread, Grad said.

The United States, Germany, and Australia have adopted the use of doxy PEP. Other countries are either still studying the issue or actively discourage the approach. It is not recommended in the United Kingdom or in the Netherlands, for example.

Among the concerns has been that using antibiotics in this way flies in the face of the principles of antibiotic stewardship — limiting use of these key drugs to try to preserve their effectiveness.

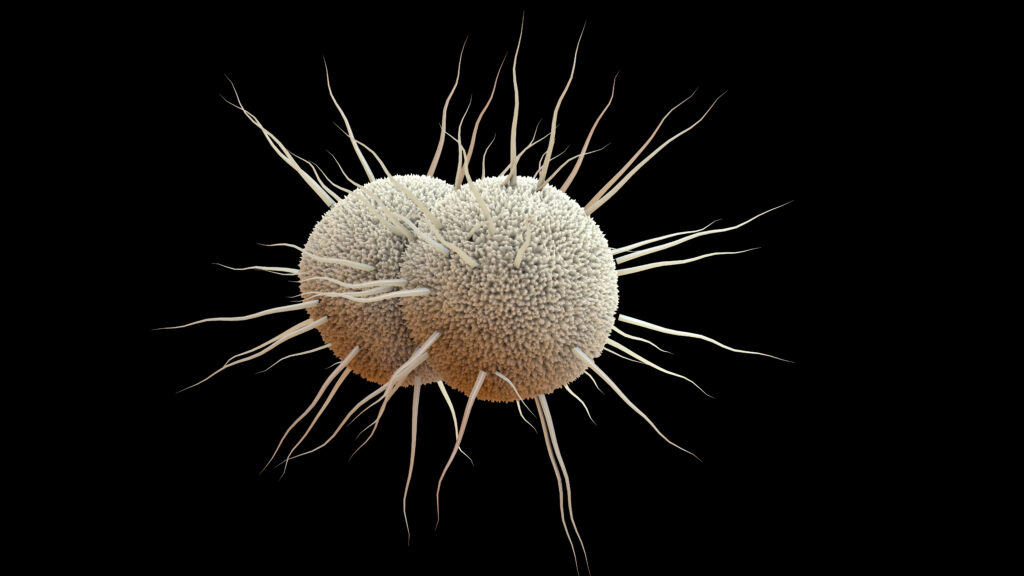

Grad and his colleagues studied more than 14,000 genetic sequences of the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the cause of gonorrhea, that were collected from patients from across the country from 2018 through 2024. The sequence data were generated by the CDC’s gonorrhea surveillance system. They were looking for a gene, called tetM, that is known to confer high-level resistance to tetracycline.

Prior to 2020, tetM was found on fewer than 10% of genetic sequences nationwide. By the first quarter of 2024, it was found in more than 30% of sequences, Grad and his coauthors reported. The sharpest increase was in the Pacific Northwest, where the earlier paper by the University of Washington researchers showed that among 2,312 men who have sex with men who were diagnosed with gonorrhea, high-level resistance to tetracycline rose from 2% of cases in the first quarter of 2021 to 65% in the second quarter of 2024.

During the time when resistance in gonorrhea rose, several factors could have contributed to the increase. But it seems clear that doxy PEP is playing a role.

“The idea being that, of course, taking antibiotics drives resistance. And you’ll see it not only in the thing you’re targeting, but also anything else that happens to be on you and in you,” Grad said.

Gonorrhea has an uncanny ability to develop resistance to antibiotics; over the course of decades, it has steamrollered its way through every one of the drugs that has been used to treat it. In fact, the only currently licensed drug that is still reliably effective against it is an antibiotic called ceftriaxone, which is not a member of the tetracycline class. Ceftriaxone, not doxycycline, is the recommended first-line treatment for gonorrhea, and resistance to the latter does not erode the effectiveness of the former. But already there are strains of the bacterium, mostly circulating in Asia, that are resistant to the drug.

Two new antibiotics that appear promising for the treatment of gonorrhea are in the development pipeline. But given gonorrhea’s history, the concern remains that they, too, could fail eventually.

Experts who were not involved in this new study said they were not surprised to see what Grad and his group found. The findings also underscore the importance of closely watching the evolving resistance patterns in gonorrhea, said Barbara Van Der Pol, a professor of medicine and public health in the Heersink School of Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Monitoring of Neisseria gonorrhoeae is an important public health need,” Van Der Pol said via email.

Jeanne Marrazzo, an STI expert who was director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases until she was fired by the Trump administration, pointed out that the very laboratory at the CDC that does this type of surveillance and testing was inexplicably closed in April — a decision that was later reversed. “We won’t have the ability to do this type of analysis if we lose the resources that CDC has available for it,” noted Marrazzo, who before joining NIAID was the director of the division of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Marrazzo said she does not believe the findings suggest it is time to reconsider the use of doxy PEP — but there should be an understanding that its benefits may be transient.

“As I’ve been saying for ages and others are too, it really needs to be seen as a bridge to an effective vaccine for [gonorrhea],” she said.

In any case, Grad suggested any effort to stop the use of doxy PEP would likely not be easy. At-risk populations have adopted the practice even without a formal endorsement from public health authorities. A study last week in the journal Eurosurveillance reported on an online survey of doxy PEP use in the Netherlands, where it is not recommended.

Of 1,633 men who have sex with men, transgender, and gender-diverse people in the Netherlands, 22% had used doxy PEP or PrEP (before unprotected sex) informally, 15% reported having recently used it, and 65% had a high intention to use it.

“I think it’s a hard genie to put back in the bottle,” Grad said. “I don’t think we’re going to stop doxy PEP, and I think doxy PEP has good clinical indications. You want to try to reduce the rates of syphilis and chlamydia.”