The present study was designed to evaluate the impact of pharmacist-led educational interventions on breast cancer awareness and BSE practices among women in Pakistan. Our findings demonstrate that a structured, pharmacy-based awareness session significantly improved participants’ knowledge of breast cancer risk factors, signs and symptoms, and available screening options. Furthermore, the intervention enhanced self-reported adoption of BSE practices, highlighting the potential role of community pharmacists as accessible health professionals in promoting early detection strategies, particularly in LMICs where specialized breast cancer services are limited.

Our study, which has incorporated this recommendation, suggests that the educational intervention conducted at community pharmacies is a good foundation and source of knowledge that should be fully utilized to improve breast cancer awareness among the local communities. Increased breast cancer awareness, which results in early cancer confirmation followed by individualized, effective treatment, is highly recommended for breast cancer control in LMICs [6]. Among the Asian countries, the highest occurrence of breast cancer is reported in Pakistan [3, 14]. It is believed that the lack of awareness is one of the major causes of inflated breast cancer mortality [9].

In the current study, we confirmed the severe lack of awareness about breast cancer symptoms, risk factors, and diagnostic techniques, as seen in the pre-intervention phase. The results are consistent with the earlier studies conducted in Pakistan, which identified poor awareness as the major obstacle to improving breast cancer survival [15, 16]. Awareness is therefore a critical factor, as cancer treatments are most effective when the disease is detected at an early stage.

The recommendation of BSE in women above 20 years is essential for individual risk realization and early detection [17], especially in a population with high prevalence, such as Pakistan. The post-intervention phase showed an increase in awareness (from 19.1% to 98.3%) and practice of BSE following pharmacist-led education. The recent finding has significantly improved the understanding and practice of BSE. The finding aligns with a community-based study conducted in Pakistan, where educational content-based intervention improved awareness about BSE [7, 18]. Considering the low BSE help for screening breast cancer, awareness about BSE may potentially be beneficial in LMICs [9].

Additionally, the correct timing of performing BSE is crucial when trying to detect the early symptoms of breast cancer. Based on the ACS guidelines, the best time to perform BSE is a week following menstruation. Only 4.7% of study participants were aware of this knowledge during the pre-intervention phase, which improved considerably to 93.8% in the intervention phase. Similarly, the number of study participants practicing BSE improved post-intervention as well. The current intervention study helped improve study participants’ confidence in BSE practice, and approximately 56.3% of study participants reported feeling confident about detecting early symptoms of breast cancer by performing BSE. The finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted in Ethiopia, where the practical competency of BSE increased from 10 (16.4%) to 43 (70.5%) satisfactory levels after the delivery of a teaching intervention [19].

The present study is the first to report that a pharmacist-led educational intervention can improve BSE knowledge and practice, which has previously been confirmed as an effective way to identify early symptoms and improve survival chances [6, 17]. The pharmacist-led educational session delivers the required information that CBE is one of the screening techniques for early breast cancer detection, as recommended by the ACS for females aged > 40 years or older. Unfortunately, only 4% of the study participants were familiar with the recommended age for mammography during the pre-intervention phase, which improved up to 86% in participants during the post-intervention phase. About 90% of the study participants became familiar with mammography as a BSE in the post-intervention phase, indicating that the pharmacist-led education improved.

In our study, the total number of study participants greater than age 40 was 46. In the pre-intervention phase, only 3 (6.52%) participants (of age > 40) had gone through mammography, but the percentage improved to 34.7 during the post-intervention phase. The improvement in screening behaviour may be attributed to more study participants becoming familiar with educational intervention through mammography, a safe method employed for early detection to improve survival chances, which improved the courage for mammography exposure. According to the findings of a study, the key factors that hinder women from undergoing mammography include being shy, fear of death/losing breast or being diagnosed with cancer, considering mammography harmful, and transportation difficulties [20]. Considering all the barrier perceptions, the participants were also informed about the safety and availability of free screening centers in the twin cities of Islamabad & Rawalpindi.

Approximately 6.89% of participants knew free screening centres exist in Islamabad and Rawalpindi. The educational services about breast cancer offered by the pharmacist at the pharmacy provided the study participants with complete information about free screening centers and their locations. This information was beneficial to promoting early mammography screening behavior in a country like Pakistan, where economic constraints and lack of resources also restrict women from undergoing expensive screening for breast cancer.

Our findings confirmed that there is limited awareness (43.6%) of breast cancer risk factors. For example, many participants have the misconception that wearing tight bras may contribute to breast cancer development. Educational intervention in the post-intervention phase analysis rectified the participants’ misconceptions. The positive feedback of study participants depicts the social acceptance of pharmacist-led educational services at community pharmacies. 95% of participants appreciated the educational service and the distribution of breast cancer educational pamphlets. The pharmacist can expand the expectations of their services for the patients and generate opportunities to contribute to health promotion activities [21].

Pharmacists’ engagement in health promotion to elevate awareness levels about health-related issues and preventive methods is a persistent recommendation of the WHO [22, 23]. Community pharmacists are the healthcare providers who are widely approachable and reliable. The findings of the present study of improved breast cancer awareness resulting from educational sessions conducted by the pharmacist support the evidence and agree that the pharmacist can potentially contribute to breast cancer control. The findings of this study prospectively suggest that the concerned health authorities make effective use of the underutilized counseling skills of pharmacists to combat the monster of breast cancer.

Limitations of the study

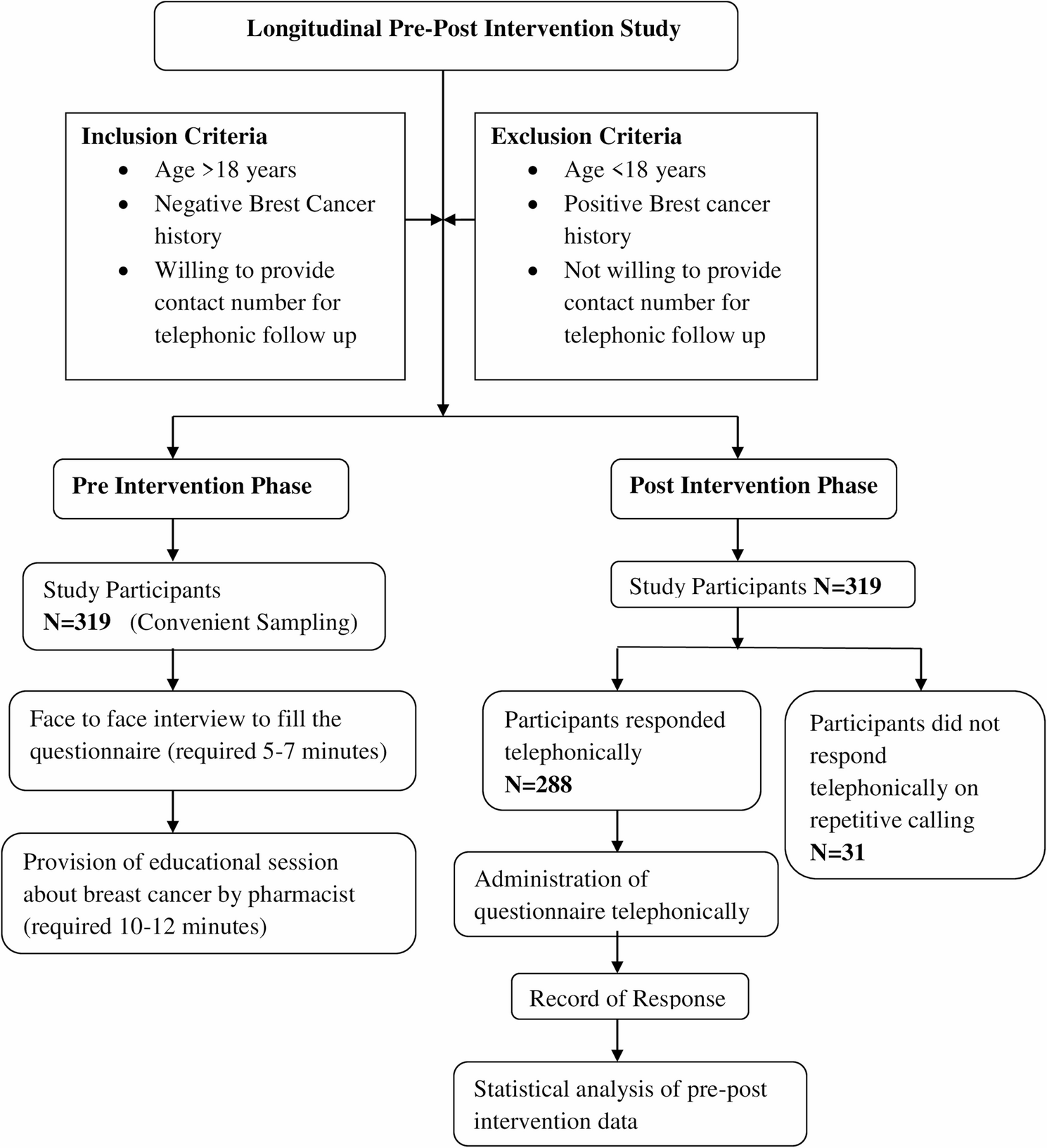

This study has several limitations. The absence of a control group and reliance on self-reported data may introduce bias, including social desirability and recall bias. Outcomes were assessed only in the short term, so this method is prone to social desirability bias and may have led participants to over-report BSE behavior following the educational session. Although no adverse effects such as anxiety or misinterpretation of normal breast changes were observed, these were not formally measured. The educational content was intentionally simplified to match the literacy level of participants, which may have limited the inclusion of complex but important topics such as genetic risk factors. Lastly, while the principal investigator received formal training, a lack of standardized pharmacist training across multiple sites may limit the generalizability and scalability of the intervention.