Participants demographic profile

Twenty women affected by leprosy with G2D were interviewed. All had taken MDT, with some also undergoing surgery or physiotherapy. Eight participants lived in SRH, while others were inpatients or attending follow-ups at the clinic. Six main themes were identified from the data (Table 3).

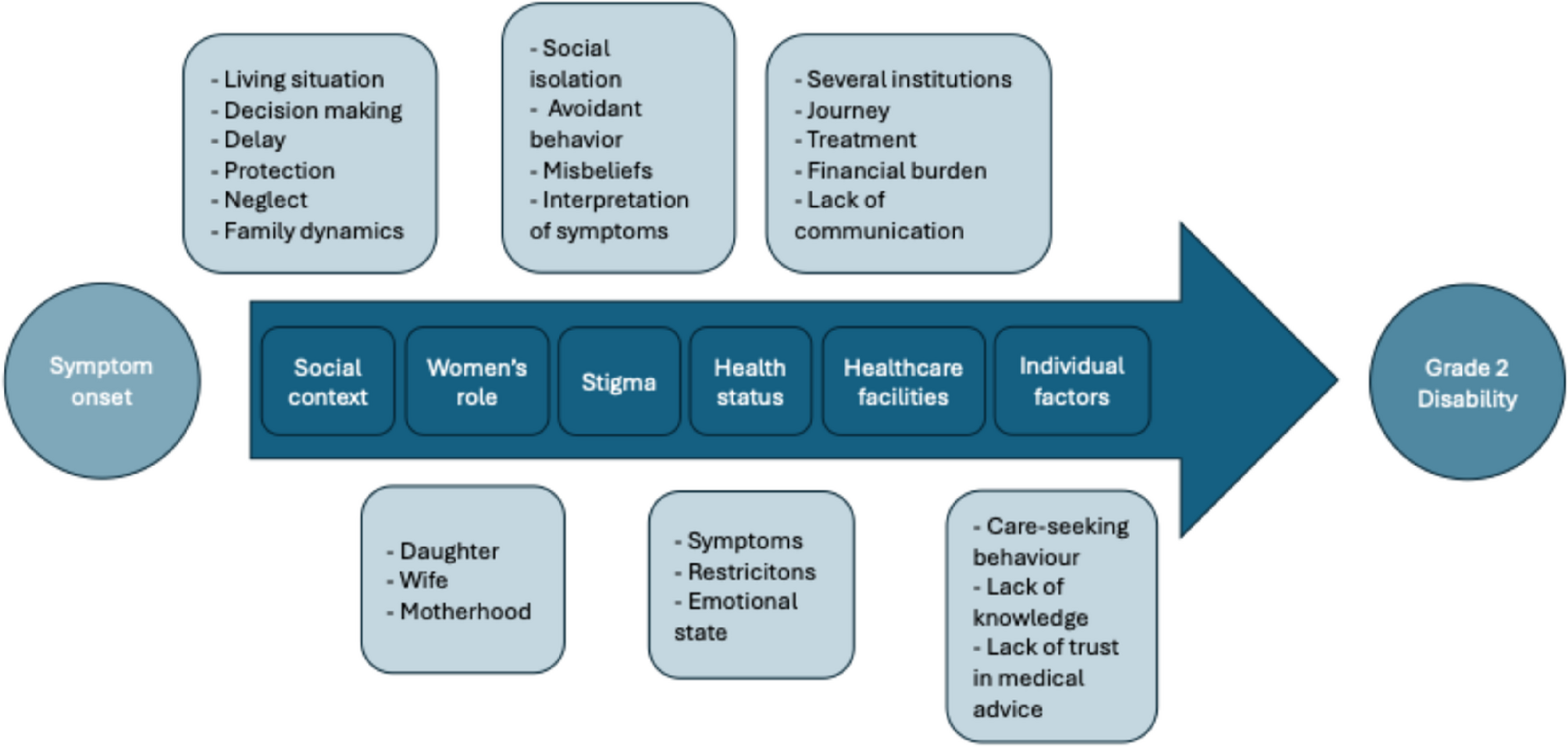

The six main themes and their interactions within a modified version of Levesque et al.’s framework [27, 28] are also visualised in Figure 1. The model shows the dimensions of healthcare access and the consequence of the identified themes on women’s health-seeking behaviour, resulting in later diagnosis and a higher incidence of G2D. The components within the arrow represent the pathway women take to access healthcare, while the elements outside the arrow indicate the themes identified in the analysis of the interviews.

A Conceptual Framework for Healthcare Access Barriers

Theme 1: social context

Living situation and the influence on decisions

During the interviews, all participants highlighted the significant role their social environment played in accessing healthcare, which subsequently affected the progression of their disease. They described how family dynamics and social influences shaped their decisions and basic needs. Both support and neglect from their social surroundings heavily impacted their futures. Most participants did not share their symptoms or diagnosis beyond their household. They explained that decisions about seeking healthcare were often made by their husbands, parents, or siblings, who were involved in both discussing symptoms and choosing when and where to get help. For example, one woman recalled, “First, I shared to mother, then father. (…) we went for hospital and treatment together” (P3). Another noted, “I never expressed to anybody that I am suffering with leprosy, only parents know” (P3). In some cases, husbands decided whether to seek care – “He [husband] decided to go to the hospital, what about this, what is the problem? You have been getting these patches and all” (P4) – while others described family members suggesting alternative medicine: “And then father and sisters said, better to take that tree leave” (P6).

Delay

Delays in accessing healthcare services for the first time varied significantly among the women, ranging from a few days to “three months” (P7), and in some cases, to several years. As one participant recalled, “After seeing the patches, after 2-3 days, I went to the hospital” (P2).

For some participants with little to no social support, and who were still children when symptoms appeared, the delay in seeking help lasted years. They recalled growing up without a supportive family, with their leprosy being discovered through accredited social health activists (ASHA) or government-led leprosy campaigns in villages. One participant shared that, despite having deformities and a foot ulcer for years, no one in her family took her for treatment, and it was only when nuns visited the village to detect leprosy that her condition was identified. “At that time, leprosy workers used to go from house to house to detect leprosy. Like that, also the sisters visited my house. (…) So, the sisters brought me here [Sivananda] and also decided that I have to stay here” (P11). Another participant was detected by an ASHA worker when she had already developed deformities. “Nobody took interest in taking me to the hospital. (…) At that time, leprosy workers used to go from house to house to detect leprosy” (P11).

Protection

The attitude of people surrounding the participants was decisive for them. Some participants received support and understanding and described the protective behaviour of their families, which helped them to deal with their situation. For instance, one participant shared how her sister’s encouragement prevented her from giving up: “I said to my sister, I want to die, I want to end my life. But sister says, better not to think like that. (…) And also, I stayed with her” (P8). Another reflected on the contrast between family support and social exclusion, noting, “Even though others were separating me from themselves, my family was with me, so that was good” (P15). Despite the support of being accompanied by her mother, one participant expressed her fear related to going to the hospital, stating: “I am afraid to consult a doctor – being a lady” (P7).

Neglect

Other participants did not experience support from their surroundings and had to deal with difficult living situations in addition to their health problems. One woman, who lost her parents at a very young age and had to perform hard physical labour during childhood, recounted a traumatic experience related to her illness. She described how, after developing leprosy symptoms, she was stigmatised by her community and even faced an attempt on her life by a family member: “So, when I was very small, at that time I lost my parents, right, so the others like my grandparents (…) used to make me work. So mostly it was chopping the wood (…). During that time my skin got hurt. And then, that wood caused infection, you know. It was untreated, it used to get infected. (…) One of those elderly ladies [in the village] she observed, and she told everyone that I am having a big disease called leprosy and do not touch me, do not talk to me (…). So, from that time onwards my family members, they stopped talking to me, they just pushed me aside. (…) I do not know how to swim. My grandfather told me he is going to wash me and then pushed me into the water and left me there, but somebody else, saw me as a poor child getting drowned, so he pulled me out and saved me” (P15).

Other participants also reported a lack of family support, growing up in households where fathers drank regularly or where the presence of multiple siblings led to a limited capacity for care. For example, one participant shared that their “Father is not that much of a caretaker, because he uses to drink.” (P6) while another stated, “My father did not take care of me. I have nine siblings, so there is no time for him to take proper care“ (P10). Another participant who did not share her problems with anyone, sought help on her own and recalled that “He [her husband] is not taking me, and he does not know. (…) He only sometimes came home, and he never took care of me” (P10).

Family dynamics

Some participants reported that their husbands left them after discovering their symptoms or leprosy diagnosis, abandoning them and marrying other women instead of facing the situation together. One participant mentioned that “Because of the patches and ulcer on my feet he left me” (P20), another one was telling: “No divorce, but due to the disease, I came here [to Sivananda] and he married another girl” (P8).

Theme 2: women’s role

Participants described various roles and responsibilities based on their living situation. One unmarried women living with her parents spoke of traditional daughterly duties and daily household chores: “I am in the house, whatever work is required, I used to prepare food, cleaning, I am bringing water” (P7). Married participants with children expressed concerns about the burden of being wives, mothers, and managing their disability, which limit their ability to fulfill tasks. One participant reports, “I suffer, I feel very bad, due to this disease and deformities and marriage, children, and husband. I am thinking more” (P5).

Despite knowing the consequences, one participant’s housework obligations led to deformities, with her loss of sensation causing repeated, unavoidable injuries. She says: “I was told how to take care, but I could not, because there is work at home, cleaning, washing clothes, cooking, and all those things” (P13).

Motherhood was a common theme in the interviews. Many mothers worried about their children’s well-being and struggled to seek help for themselves while caring for their children. One participant shares “I worry about the children. My hand is like this, how to look after the children, they should be safe. That’s why I kept them at my sister’s house. I am worried more about children and my deformity” (P8). Another participant explains, “I have to leave the children also, so I have to find somebody to look after the children, that was also very difficult. (…) When I went to the hospital, I could not work, so I could not earn money to feed the children” (P10).

The participants’ identification as mothers and wives is prioritised over their own health. One participant recalls. “When I came to Sivananda, they advised for admission for ulcer and deformities in my hand, but my husband said due to children I cannot stay here. I didn’t stay at that time, I went home. (…) Husband told, better not to get admission, because children are there at home, to look after children” (P9).

Children and families did not only represent a barrier to healthcare services for some, but they were also directly impacted by the participants’ deformities. One participant discussed her role as a mother, which she must fulfil before she can seek help. She explains, “Women’s problem is more, compared to men. We have got to do things, then only us. How to do it, small kids are there (…). Because due to this problem, I am not looking after the children in a good way, I always think that. Because I am not well. I am not able to feed them properly. I am not able to dress them properly. I worry about that. Before I got this, I did go to the park, (…) and play. We play together. I used to go to the school with my kids. (…) I feel very sad. I am not able to take children properly, I am not able to lift them” (P4).Another participant delayed visiting a doctor due to her pregnancy and her role as a wife and future mother. She recalls, “Because that time I was pregnant, I was afraid to go to the doctor, to take medicine and all. That’s why I never went to the doctor” (P9).

Theme 3: stigma

Another key theme in many interviews was the stigma participants faced due to the social consequences of leprosy.

Social isolation

Participants were treated differently after their diagnosis, leading to social isolation, loneliness, and insecurity. One participant describes, “Before I was diagnosed, everybody was together, we were a happy family, joined family, but then after I was diagnosed with this, then they started separating themselves” (P19). Another shares, “They said that I should be separated, my plate, my glass, everything should be separated – isolated, isolated” (P8). One participant explains, “Parents also never say to anyone that I am suffering with leprosy, because of social stigma” (P7).

Participants faced stigma not only due to leprosy but also because of deformities and disabilities. One women reflects, “Some of the relatives and neighbours (…) they say that they don’t mingle with me. When I am going there, their faces are completely changed. (…) Why am I coming to their house like that? (…) They don’t know I have leprosy, but by seeing my deformities in the hand and ulcer, when I go and move, their attitude has changed” (P9).

Following the advice of other affected patients and their experiences with stigma, one participant decided to move to Sivananda. She recalls, “So, I was taking the medicine and going back home. But then, some patients were here, they told me, I cannot live outside with my deformities, I stay here, and they got me married with one person here” (P14).

One participant faced the disease and its consequences alone, saying, “I had nobody to share my feelings, there is nobody to hear me, I had to process it on my own, and the sadness that is there, I have to face it on my own and keep it within me” (P19).

Avoidant behaviour

Out of fear, some participants avoided social interactions with family and friends. One participant shares, “So, on my own, I felt bad, you know, when there was a family occasion like marriage, you have to sit and eat. And at that time, because of my deformities, I would have problems. So, I myself avoided, but the others did not say anything to me” (P16).

Furthermore, the medications’ side effects, like temporary skin darkening, also led participants to avoid social contact. One participant explains, “While taking the medicine, I felt weakness, then colour changed, black colour, (…) for 2 years face is completely black. When I became black, I never attended any functions, stayed at home” (P9).

Many female patients indicated that fear of stigma shaped their decision to attend healthcare facilities. One participant, who lied to her neighbours about her visits, explains how she copes with the situation: “If someone knows, in the bus, when I am traveling, some of known persons could be there. By seeing my foot maybe, what are they thinking? (…) Being afraid of that, I always put socks, shoes, and socks. I use to cover that ulcer. (…) Some injury, due to that only, I put bandage” (P9).

Another interviewee feared discrimination from other patients at the healthcare facility, so she tried to visit as infrequently as possible. She recalls, “By seeing me, they might think that I am suffering with leprosy or something. They could be thinking or saying go away from this hospital (…). I used to think that” (P7).

Misbeliefs

Leprosy was put in context with misbeliefs. One participant mentioned, “Neighbours told me that my grandparents had it, that is why I got the disease. They did not tell me that it is leprosy, but grandparents had it, so witchcraft is there” (P13).

Some patients felt nothing could help them; they did not trust the medicine or surgeries the healthcare workers offered. This left them feeling helpless, resigned to their fate. One participant stated, “I accepted the fact, that leprosy patients will get this kind of deformities” (P14).

One woman described her situation at home, as her husband thought erroneously that she could transmit the disease to her children via sharing food, even though she had started the treatment at that time already: “Husband is telling, when I am feeding, first I have to feed the children, then I take (…) That is why I feed my children first then only I will go for my meal. Husband is telling for our children’s security only. (…) I should obey, that is good” (P9).

Interpretation of symptoms

Participants understood and interpreted the symptoms in their own ways. Some mentioned the reasons and explanations for the changes as they understood them. One participant suggested, “Maybe some effect from some religion – in villages, there are certain rituals, which do cause some kind of difference in the skin” (P20). Another participant recalled, “I used to sleep outside under the tree. Some insects are crawling, and it is that patches appear. First, I thought of that” (P2). A third participant connected the symptoms to a recent childbirth, saying, “I thought, ok, that is due to childbirth, I have given birth to my last child, that time, my health condition is not good, due to that, there is weakness” (P5).

Theme 4: health status

Symptoms

Participants described their first symptoms, the deformities they developed over time, and how they felt until they were diagnosed with leprosy. They mentioned functional limitations, such as “General weakness” (P7), or “There is no power in my hand, (…). The work also was difficult for me” (P10). When asked if they had experienced a loss of sensation before, one participant replied: “Without knowing, I would hold the boiling vessel and get burns, and that’s how I lost my fingers. Maybe I did not have a clear distinct of that, loss of sensation” (P11).

Participants also discussed side effects of the leprosy medication, with one recalling, “When I used to consume MDT, I used to get vomiting and all” (P7).

Most participants mentioned visible body changes, particularly ulcers, as one of the most prominent and limiting symptoms. As one stated, “Repeatedly, I am getting the ulcer. (…) they removed my foot, because bone was there (…) and bone was infected” (P12).

Restrictions

Participants described their restrictions due to their disabilities and the drastic effects on their daily lives. One woman explained, “I am not able to do any work or daily activities, I am away from all daily activities, not able to hold any objects. I am all dependent” (P6). Another recalled, “Agricultural work I used to do, but once I had problems in the foot I had to stop” (P12). A further women affected by leprosy reflected, “I cannot dress myself properly, that is the problem. And myself, even hair, even tight only, not possible” (P4).

Participants were forced to interrupt or stop their education, having a long-term impact on their prospects. One participant recounted “After this, due to health problems, I never continued education, I stopped” (P6). Another described, “I used to work in a school, I used to sweep the floors and things like that, but now, I had to stop, I am not working, I am begging.” (P15)

Emotional state

The symptoms evoked different reactions in the women: Some were anxious and worried, whereas others did not care about their symptoms that much, as long as they were not experiencing pain or restrictions on actions in their everyday lives. One participant recalled, “By seeing the patches, I was a lot afraid” (P6). Another said, “We were thinking (…) it would go away on its own. We did not think it is leprosy” (P16).

One participant reflected on her relationship and her feelings towards her husband because she was no longer able to do the household chores as before due to her disability: “I am imperfect. (…) I feel guilty” (P4).

After their diagnosis, participants felt distressed and saddened by their circumstances. They described the emotional impact of learning they had leprosy and the resulting change in how others treated them. Some reacted negatively, losing hope. One participants recounted, “Actually, when I realised that I was having leprosy, I used to feel very upset. It was very hard for me to accept it, because before that I did not accept it, did not care about it. (…) But after my husband’s family started separating me from the whole group, that was the time I started getting upset” (P15). Another expressed a similar feeling: “I was very upset, I cried a lot, I cannot express the sadness I had at that time, I cannot express in words” (P17). For some, the despair was even more severe, “Knowing what it is, I wanted to get suicide” (P7).

One woman described her reaction to other people’s behaviour when they made her eat her food in a different room: “That caused immense sadness, then I started crying and I started a big fight. (…) I was so hurt and angry and upset about what is happening and then also I thought why to live? People are treating me like this, they are separating me from everybody else, better to die” (P15). Alongside personal anguish, participants also expressed concerns for their future and that of their children. As one put it, “To get partner, I am feeling due to that disease. If they came to know that disease, then I am afraid for that. Sometimes people divorce due to leprosy” (P3). Another admitted, “I am scared that I will transport the disease to my son. So, I used to pray that my children should not get it” (P10).

Theme 5: visits at healthcare facilities

Several institutions

Many participants visited multiple facilities, with the time before receiving a leprosy diagnosis ranging from a few days to several years. One participant recalled, “At least five hospitals I went to” (P13). Another noted “Same day we went and collected the medicine” (P6). For others, it took longer, one said: “One month” (P9).

The repeated visits to multiple medical facilities and the lack of symptom improvement caused participants to become increasingly worried about their health. One expressed, “I was worried (…), what is the disease, what is that? Just worried. Why is it happening? Getting pain and patches, so far, we have consulted many doctors, and I have taken many medicines. I just worried and used to cry. (…) Still, it is not subsided” (P6).

Journey to healthcare facilities

Participants encountered multiple challenges accessing healthcare, including distance, costs, time constraints, and the need for accompaniment, with their mobility further hindered by physical deformities. One participant shared, “My health condition was not good. I was not able to walk. My brother was able to lift and hold me and sit on the bike. He used to take me” (P7). For another, her disability and amputations led to the need to change their way of getting to a healthcare facility: “First, we used to come by bus, but recently, the last time we came by taxi” (P12). Many described public transport as burdensome and time-consuming. One woman explained, “I have difficulties with the bus travel because they will not stop where I say, they will stop at different places. (…) You have to be very dominant and jump” (P10), while also noting, that it takes her “3 hours to get here” (P10).

Another participant recounted her journey with her mother to the healthcare facility as follows: “Train, so we had to change three times. From my place to railway station, we had to go by bus. Again, from there, we had to catch the train, come here, again, we had to get on, again take another bus when I had to come here. So, it was difficult for us, especially as ladies, women, you know” (P16).

Treatment

Participants received various treatments for their leprosy, including naturopathic remedies, medications, MDT, physiotherapy, surgery, and special footwear. One woman recalled, “Some trees and leaves, in some villages they have given some medication” (P6). Another explained, “Right hand also, they did small skin graft, because already abduction of the fingers” (P7). A further participant described, “They gave treatment, treatment in the sense of medicine, injections, and rest” (P12).Some participants relied on external resources, like custom-made shoes, to manage their daily lives. As one participant put it, “I cannot walk without them” (P11). Some symptoms were only discovered at healthcare facilities, such as the physiotherapy department: “I never noticed that weakness is there. I never feel that this hand has become weak or something, I never felt it” (P1).

Eventually, all participants were referred to the SRH in Hyderabad by other healthcare workers, patients, or people familiar with the facility. Some, however, were referred only after their medication was finished. One woman explained, “A big problem was there, when I went to the first hospital, that time only weakness is there, no deformity. But they said, only after one-year treatment we will send you. Meanwhile, I got deformity” (P3).

After reconstructive surgery, participants reported high satisfaction with their care and treatment. One participant stated: “That time I am facing the pain and deformity, but now, there is no pain, no deformity, that’s why I am free, I feel happy” (P7).

Financial burden

Discussions on healthcare visits often highlighted the financial burden, especially with private facilities, making medical bills a significant challenge and a deciding factor for some in seeking help. One participant noted, “Some test they did, for that and medication and consultation I had to pay money” (P7). Another explained how costs influenced her healthcare access: “So, whenever I saved money, I used to go, otherwise I was not able to” (P10).

Lack of communication

Some participants were diagnosed with leprosy at healthcare facilities but were not informed about the disease, receiving treatment or referrals without understanding their condition. One woman recalled, “I completed MDT for one year, even though I never knew it is leprosy” (P6). Another explained, “So, when I got that boil, I went to the government hospital near my place, and then they gave this MDT leprosy medicine. But they did not tell me, that it is leprosy, so even at that time, I did not know that I have leprosy, but I was taking medicine” (P16).

In some cases, healthcare workers discussed the diagnosis only with family members or husbands, not directly informing the participants as patients. As one participant described: “P: They have diagnosed, but they never told me. Only my husband knows. (…) That doctor said to my husband and husband took medicine for one year. (…) He knows that I am suffering with leprosy, but he never tells me, that I am suffering with leprosy. But medication he has given me every month” (P4).

Theme 6: individual factors

Care-seeking behaviour

One participant said that she did not go and see the doctor anymore after developing deformities because she thought that the medicine she got there did not help her: “Before this, I used to go, but now I am not going anymore. If I have some fever or anything; I, myself, will just go and get the medicine. (…) That medicine is not suiting me” (P12).

Lack of knowledge

An important aspect of each interview was the participants’ lack of knowledge about leprosy before visiting a healthcare facility. Most women affected by leprosy stated they knew nothing about the disease before being diagnosed and educated. One participant admitted, “I have never seen any suffering leprosy patients; I don’t know anything about leprosy before diagnosis” (P8).

For one interviewee, the only association with leprosy came from seeing people in her village who went begging: “I did not know what is leprosy. When I saw the people walking and begging. And I have heard people talking, these are leprosy patients, so I have seen them” (P10).

Others lacked general medical knowledge. One participant, raised in a rural area without family support, explained, “I was very young at that time; I did not know that somebody called a doctor is there” (P15).

Lack of trust in medical advice

Individual attitudes towards the disease, treatment options, and healthcare workers’ advice were often dismissive, leading to poor treatment adherence. Some participants expressed a sense resignition and felt they could do nothing to change their situation, as one remarked, “It is just fate” (P20). Others openly admitted ignoring medical instructions. One woman recalled, “Then they told me, better stop that medicine, the Prednisolone tablets. But I continued, even though the doctor said, better to stop” (P6). Another confessed, “I would go and as soon as they would bandage me, I would go and put it in the water. So, that is why, actually the treatment also did not go according to plan. Medicine also, I would just show that I am swallowing but then spit it out” (P15).

Awareness gap

One of the biggest hurdles for participants was recognising symptoms and the need for urgent help, with some overlooking the loss of sensation due to focusing on basic needs. One participant recounted, “While cooking, I was developing blisters and ulcers, but I did not realise that it is loss of sensation, and I did not know the disease” (P14).