Hematologist Robin Foà, MD, has done more than simply watch his specialty transform over the past 50 years. He’s helped to lead the revolution in blood cancer care, especially for the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL).

Foà is now a professor emeritus of hematology at Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, and he says he’s “officially retired” and should be taking it easy. But he’s still working.

This year alone, Foà has co-authored at least nine published studies, plus a guide for treating adult Ph+ ALL for the journal Blood, a commentary in the Cell Press journal Med, and a review article for The New England Journal of Medicine about 25 years of progress in treating the disease.

In an interview, Foà spoke about his professional journey, the past and future of hematology, and his love of chronicling the world through photography.

Can you tell us about your early life and how you came to hematology?

It’s a complicated family story. I was born in England because my father had to leave Italy in late 1938 or 1939 due to the racial laws because he was Jewish. From Torino, Italy, he went first to Paris, France, then to England.

When World War II started in 1940, being Italian, he was considered an enemy and interned. In the Lake District he met my mother, who was a teacher from Wallsend in Northumberland. They married in September 1945, after the war finished.

Following the war, my family had a choice between reuniting in New York, where my grandparents and my aunt had spent the years of the war, or returning to Italy. They chose Italy.

I was borne in Wallsend and grew up in Torino, where I graduated from medical school and initially worked in the pediatric clinic.

How did you end up at Hammersmith Hospital in London?

That’s a strange twist of fate. When I was a medical student in Torino, the professor of pediatrics organized a meeting and invited someone from London — Professor Gordon Hamilton-Fairley, who became Sir Gordon.

I was asked to help with translation at the airport. When I took him back, he said if I ever needed help in the future, to get in touch. Years later, when I wanted to work in London, I had two options. Tragically, Professor Hamilton-Fairley was killed by an IRA bomb in London in 1974 — he was taking his dog for a walk when it touched something under a car.

The other contact person in London was Daniel Catovsky, MD, at the MRC Leukemia Unit, Hammersmith Hospital, London.

What was Hammersmith like in those days?

Hammersmith in the mid-1970s was one of the centers of hematology in the world. I spent 3 years there, and it completely changed my life. I went from pediatrics to working on chronic lymphocytic leukemia [CLL], which doesn’t exist in children. It’s a disease of the elderly.

You’ve witnessed dramatic changes in leukemia treatment. How do today’s outcomes compare to what you saw early in your career?

It’s been a revolution.

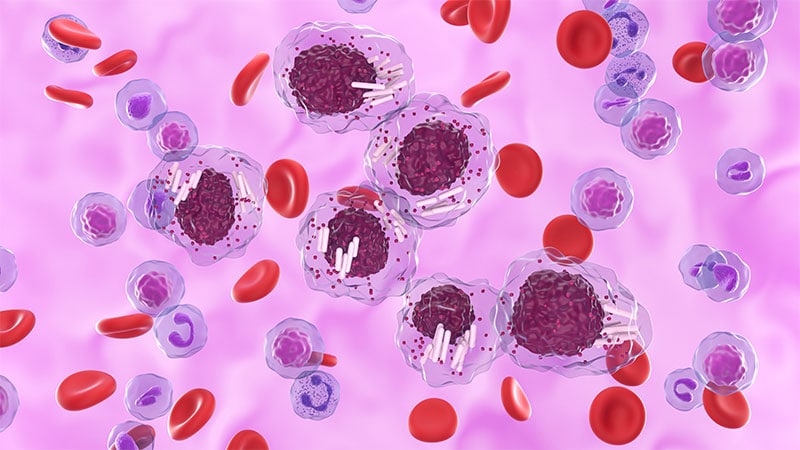

Take CLL — the most frequent leukemia in the Western world. In the old days, the only option was chemotherapy. Nowadays, chemotherapy is almost not used anymore, at least in developed countries. We have targeted drugs that provide better survival, better disease control, and fewer long-term side effects.

Even more striking is acute promyelocytic leukemia. Through research, we understood that it’s a matter of blocked differentiation of leukemic cells. Now, acute promyelocytic leukemia is cured in the large majority of cases without chemotherapy, using all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide.

What has your work with Ph+ ALL produced?

This has been one of my major focuses. Based on the results obtained in chronic myeloid leukemia [CML], at the end of the last century we designed the first protocol to treat older patients with Ph+ ALL using only the TKI imatinib plus steroids in induction — and no chemotherapy.

It was revolutionary because this was considered the most lethal hematological malignancy. We found that all patients went into remission.

Since then, in all national protocols conducted by the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto[Italian Group for Hematological Diseases of Adults], adult patients — with no upper age limit — received a second- or third-generation TKI, dasatinib or ponatinib, plus steroids.

More recently, we added immunotherapy with blinatumomab, a bispecific monoclonal antibody in consolidation. We published the results of the dasatinib-blinatumomab trial in The New England Journal of Medicine in October 2020. It showed virtually all patients achieved remission with 88% disease-free survival at a median follow-up of 18 months.

The follow-up, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in December 2023, showed that you have survival rates between 75% and 80% at four and a half years, the best data ever reported. Half of the patients never received chemotherapy or transplant.

What’s the significance of avoiding chemotherapy and transplants?

I can give you a real example. Many years ago, a young woman from Eastern Europe came to see me. She must have been in her 20s. She was diagnosed with CML and told she needed imatinib for life.

When she asked about the cost — possibly over 50 years of treatment — her family said it was literally impossible to afford. The alternative offered was transplant.

The pill would obviously be the best option. So I told her to come back as an undocumented immigrant, present to our emergency room, and we would treat her because in Italy, we’re obligated to treat all patients regardless of status. She did that. She came, and we could give her the drugs.

This shows the tragedy — offering a transplant with high mortality risk instead of a simple oral medication because of cost.

You were the president of the European Hematology Association (EHA). What did you focus on during your tenure?

I stayed for 6 years in leadership roles — 2 years as president-elect, 2 years as president, and 2 years as past president. In other years, I was the chairman of the Education Committee and the Outreach Unit.

It’s been a great part for my life, no doubt about it. EHA has grown to become a very important society.

I promoted outreach activities to more or less everywhere in the world. Big societies like EHA and American Society of Hematology have a duty to do this. They can help, and have indeed helped, other people.

For all the work done, I was awarded the EHA Education and Mentoring Award in 2018 and the EHA José Carreras Award in 2023.

What challenges do you see on the horizon for hematology?

The main challenge today is accessibility and sustainability. We have precision medicine that changes prognosis, but costs are high. It’s unacceptable that only the very wealthy can afford these treatments. We need to make them feasible for as many people as possible.

Also, we need continued funding for research. The world is cutting funds everywhere, and all the advances I’ve discussed stem from research investment. We have the technologies now — single-cell analysis that’s potentially phenomenal but extremely expensive. We need funds to utilize them.

What advice would you give young hematologists?

Hematology is a beautiful discipline that needs to combine clinical work with laboratory research. You need to work in the lab, understand the technology, and appreciate what can be derived from laboratory techniques.

I could tell you stories of patients who write to me 20 years later who should have been dead but are still alive. I’m writing up the story of four older patients with Ph+ ALL who lived many years on a TKI alone, even into their 90s! In the old days, they would have been dead in a couple of months.

You’re also an accomplished photographer with over 10 published books. How did that passion develop?

I always loved traveling, and I started taking shots during my trip to Kenya in 1974 with a colleague who was an excellent photographer. I had a tiny Minox camera — the kind spies were using to take photographs of documents. You can imagine that trying to take a picture of an elephant in the savannah with a Minox was pathetic.

When I saw my results compared to his, I got my first proper Nikon camera.

I love traveling. Nature has always been a key point for me, but also people. I have so far published 12 photography books.

What’s next for your career?

I’m officially retired, and I should relax. I no longer have any clinical or administrative responsibilities, which is a relief.

I do continue to coordinate a large research group in Italy that I’ve had for 14-15 years, and that’ll take me until the end of next year. This certainly keeps me very active.

Do you have any final thoughts for our readers?

We’re living in an extraordinary time in hematology. We’ve moved from the worst outcomes to treating many leukemias without chemotherapy in a matter of 30 years, which isn’t long in medicine.

Every year we see advancements and improvements. The relationship with patients is completely different now because you’re not telling them they’re going to die. You’re offering hope and often a cure.

The key is combining rigorous science with compassion for patients and never lose sight of the global responsibility we have to make these advances available to all patients, regardless of where they live or their economic circumstances.

Foà disclosed relationships with the Italian Association for Cancer Research, Amgen, Autolus, and Merck Sharp & Donne.