Overall RASR strategy and policy

Almost all survey respondents (97.5%, 78/80) reported that their programme follows the 1–3-7 approach. Half (20/40) of the malaria programme stakeholders reported that this strategy was implemented across all areas of Cambodia, while the frontline health workers reported that it was applied only in malaria elimination areas (68%, 27/40; Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 3). FGD and IDI participants affirmed that they used 1–3-7 approach in case notification, investigation and classification, RACD and focus investigation of new active focus.

Implementation and timeliness of RASR strategy

Case notification

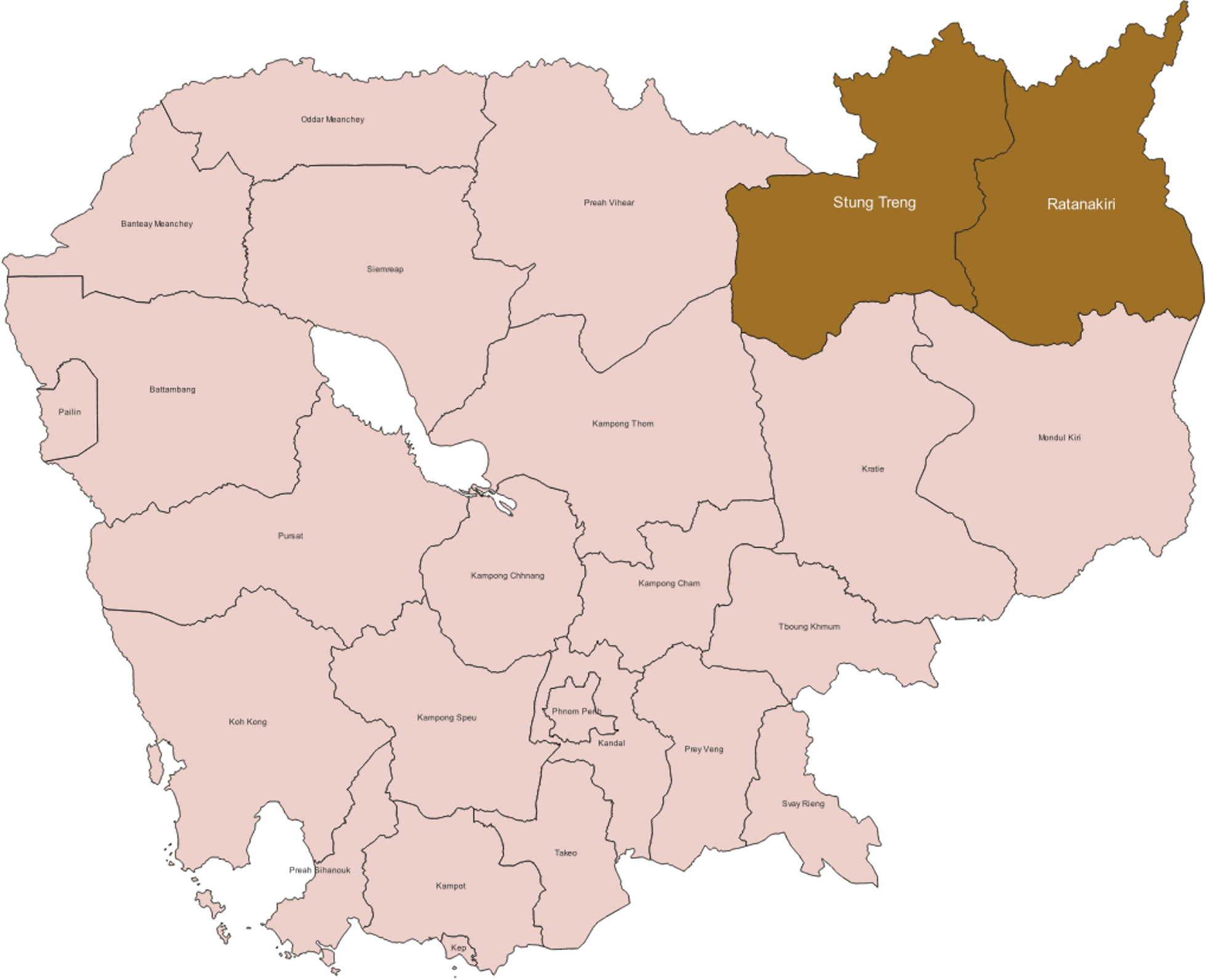

A total of 2727 malaria cases were reported in Ratanakiri and Stung Treng Provinces between January 2020 and September 2022 out of which around 72% of cases in Ratanakiri and 59% of cases in Stung Treng were classified and notified on the same day as diagnosis in 2020 and 2022. Timeliness of case notification was lower in both Provinces in 2021 compared to 2020 and 2022 (42% in Ratanakiri and 36% in Stung Treng; Table 1). Survey participants also claimed that they completed the case surveillance report nearly always within the stipulated time frame (78%, 62/80) in 2020 and 2022 (Table 2).

According to surveys, almost all frontline health workers had access to mobile phone network (97.5%, 39/40) and internet (95.0%, 38/40). However, only about half of the frontline health workers (47%, 18/40) reported having access to reliable internet connectivity at their worksite or village for case notification (Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 4). Direct telephone calling to the respective staff was the most common case notification method among the frontline health workers (85%, 34/40), while many malaria programme stakeholders mentioned the electronic reporting system (80%, 32/40; Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 5).

Case investigation

Most surveyed malaria programme stakeholders (83%, 33/40) and frontline health workers (68%, 27/40) indicated that case investigation is initiated within one day of confirmation of an index malaria case (Table 2). Although many survey participants (83%, 66/80) (Table 2) suggested that all malaria cases had a case investigation completed, they also mentioned common reasons for incomplete case investigation such as cases moved to other districts and subsequently loss to follow-up (28%, 22/80), and inability to contact or reach the case (11%, 9/80; reasons detailed in Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 6).

“There are villages located quite far (from the town/health centre. It is difficult to make a phone call or go there. This makes it challenging for the Team to conduct case investigations.” (A malaria stakeholder in FGD, Stung Treng province)

The survey participants responded that case investigation was triggered by malaria cases reported to the national level (41%, 33/80) and peripheral level (68%, 54/80) of the malaria program. Many survey participants telephoned the index case to make an appointment for case investigation ahead of visiting to their home (65%, 52/80). If the case was not at home when they visited, they telephoned the index case again to schedule another appointment (76%,61/80) or visited the case again later the same day (58%, 46/80; Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 7).

Most frontline health workers in the survey were personally involved in case investigations (88%, 35/40). Many malaria programme stakeholders (73%, 29/40) reported that VMWs performed case investigations, while the remaining (28%, 11/40) reported that health centre staff or others performed it (64%, 7/11) (Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 8).

About two-thirds of the survey participants (66%, 53/80) claimed that they mapped the location of the index case during case investigation. Furthermore, a majority of participants in the survey (90%, 72/80) reported that they obtained travel history from the index case, including travel within (93.1%, 67/72) and outside of the district of residence (89%, 63/72), and outside of Cambodia (73%, 47/72) (Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 9). The malaria programme stakeholders in IDIs reported that they asked where the malaria-positive person had been sleeping two weeks before, and who were the co-travellers.

Based on the travel history, they classified the malaria case as either (1) local/within-village transmission, (2) out-of-village transmission, (3) imported case, (4) or relapse/recurrence. Of the survey participants, 68% (54/80) defined imported cases as cases originating from another country, while the remaining respondents (33%, 26/80) defined imported cases as cases from another district within the country (Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 9). A staff in IDI explained the four classes of malaria cases.

“There are four types of malaria cases. The first type, L1, is cases where the origin of the case is local from the patient’s village of residence as defined by the fact that the patient has slept every night at their village of residence within the last 2 weeks. LC is also local cases, but this time the patient has slept at least one night outside of their village of residence but within Cambodia over the past two weeks. For imported cases called IMP, the transmission origin is from another country and the criteria is that the patient has slept at least one night in another country within the last two weeks. Lastly, there’s a type called REL/REC for cases from a previous episode of malaria, where the patient has recent P. vivax infection and has had P. vivax within the last 12 months”. (A malaria stakeholder in IDI, Stung Treng province)

Most survey participants (89%, 71/80) reported that there was periodic supervision on conducting case investigations, which could be monthly (54%, 38/71), quarterly (20%, 14/71), or yearly (10%, 7/71). The VMWs and MMWs reported that they were supervised during case investigations by staff from a health centre (79%, 30/38), district health department (29%, 11/38), provincial health department (13%, 5/38) and Catholic Relief Services (11%, 4/38; Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 10).

All 80 survey respondents reported that the individuals conducting case investigations had received case investigation training organised monthly (18%, 14/80), quarterly (8%, 6/80), yearly (53%, 42/80), or biennially (23%, 18/80; Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 9). Concurrently, VMWs from the FGDs stated that trainings related to 1-3-7 approach, including case investigation and RASR guidelines were provided to them by the national malaria programme, provincial health department, their partner organizations and health centres.

Reactive case detection

Between 2020 and 2022, 1,008 malaria cases (60 imported or out-of-village transmitted cases of Plasmodium falciparum or mixed species and 948 within-village transmitted Plasmodium vivax cases) were eligible for RACD; about half of the cases (54%, 541/1008) had RACD carried out within three days of index case classification. The timeliness of RACD was similar in 2020 and 2022 but varied according to province (Ratanakiri, 89%; Stung Treng, ~ 45%) and was lowest in 2021 (73% and 24% in Ratanakiri and Stung Treng respectively) (Table 1).

Almost all surveyed malaria programme stakeholders (92.5%, 37/40) reported that their malaria elimination programme practiced RACD using rapid diagnostic test (RDT) (100%, 80/80). Other tools used in RACD included microscopy (15%, 12/80), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (2.5%, 2/80) and serology (1.2%, 1/80) (Table 3).

Nearly half of the survey participants (49%, 39/80) reported that RACD was triggered only by local cases. Less than half of malaria programme stakeholders (48%, 19/40) and only about a quarter of VMWs and MMWs (28%, 11/40) responded that screening for RACD was triggered by local and imported cases (Table 3). In IDIs, a malaria programme stakeholder reported that RACD was triggered by imported and domestic P. falciparum or mixed cases and within-village transmitted P. vivax cases.

“Reactive case detection was performed for cases of Plasmodium falciparum or mixed infection found as domestic cases (LC) or imported malaria (IMP), and village cases for Plasmodium vivax cases (L1).” (A malaria stakeholder in IDI, Stung Treng)

Majority of the survey participants reported that RACD always screened the household members of the index cases (92.5%, 74/80) and included all the household members (92.3%, 72/78). They reported that RACD also included screening both asymptomatic and febrile neighbours (81%, 65/80; Table 3). The median number of households screened was 20 (min–max: 3–40, n = 78). Most survey participants reported that minimum screening radius was within one kilometre around a positive index case (83%, 55/80; Table 3). IDIs revealed that co-travellers of the index cases were also tested during the RACD.

“The activities of reactive case detection include testing for malaria among all members of the index case household and 20 neighbouring households, or people who reside within one kilometre around the index case and also testing for malaria among co-travellers who may miss in the initial testing by geographical criterial.” (A malaria stakeholder in IDI, Stung Treng province)

Focus investigation and responses

Secondary data analysis revealed that the majority of the eligible foci with local P. falciparum or mixed cases were investigated and classified within one week (71%, 41/58) after an index malaria case had been reported. Notably, there were zero eligible cases for focus investigation in Ratanakiri Province in 2020 and 2022. In 2021, exactly half of the foci in Ratanakiri (50%, 5/10) were investigated within seven days. Stung Treng province achieved > 90% timeliness in focus investigation in 2020 and 2022 but was lower in 2021 (18%, 2/11) (Table 1).

Malaria programme stakeholders in the survey reported that focus investigation was initiated within one day (88%, 35/40), three days (7.5%, 3/40) or one week (5%, 2/40), respectively, after a malaria case was reported (Table 2). A programme staff explained in an IDI that focus investigation was triggered by confirmed cases of within-village transmitted P. falciparum or mixed infection, and it was expected to be completed within seven days.

Based on the survey findings, focus response began within one day after a malaria-positive case had been reported (73%, 58/80) (Table 2). The most common response activity among the survey participants was raising awareness about malaria transmission (93.8%, 75/80), while frontline health workers also reported malaria prevention (75%, 30/40) and additional vector control activities (60%, 24/40) as focus responses (Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 11).

Notably, both malaria programme stakeholders and frontline health workers in the survey thought that information gained from case and focus investigations did not influence the response activities (71%, 57/80). Furthermore, the malaria programme stakeholders believed that the current RASR activities were not sufficient to target MMPs (53%, 21/40) and P. vivax malaria (63%, 25/40) (Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 12).

Acceptability and feasibility of RASR strategies

Acceptability of RASR strategy

According to FGDs and IDIs, programme stakeholders expressed satisfaction with the existing RASR strategy and cited positive outcomes in the malaria elimination programme associated with the strategy. In addition, the VMWs were also satisfied with their increased opportunities to participate in surveillance activities and works with the malaria programme stakeholders. Moreover, MMPs participating in the FGDs expressed their desire to see the RASR activities continue in their communities. Overall, the current RASR strategy was acceptable across all levels of malaria stakeholders, frontline malaria providers and community members.

“The current malaria RASR strategy and activities are acceptable to different malaria programme stakeholders at different levels across various geographical areas because we see a better result (in the malaria elimination program) after initiation of the 1-3-7 strategy.” (A malaria stakeholder in IDI, Ratanakiri province)

Feasibility of RASR strategy

The FGDs and IDIs data highlighted several factors that support the feasible implementation of the RASR strategy in Cambodia. A senior officer in IDI mentioned the “Malaria Eradication Commission”, which has extended structure from community to national level. The committee secured improved support and commitment from the politicians and the government to the RASR strategy. In addition, both the malaria programme stakeholders and VMWs committed to the RASR strategy no matter what the circumstances given their dedication and hard work contributed to the success of the RASR strategy. Moreover, a district level malaria stakeholder in an IDI believed that the involvement of local authorities with great influence on the community participation in the surveillance activities, was a key to successful implementation of RASR strategy. They also cited the resources support of partner organisations as a helpful factor in successful implementation of RASR activities.

“The reason why RASR strategy is working is because of the hard work and dedication of malaria programme stakeholders and volunteers (VMWs), who are committed to the (RASR) strategy, no matter what the circumstances.” (A malaria stakeholder in IDI, Ratanakiri province)

Furthermore, malaria supervisors in FGDs also claimed that there were adequate commodities and human resources to implement the RASR strategy. They stated that the Ministry of Health and its partner organisations supplied the materials monthly and the district health department would supply the required commodities once they requested them in a report. They also felt that the human resources available through the district and community health centre, partner organisations, VMWs and MMWs were sufficient to implement the RASR strategy. A malaria programme stakeholder in the IDI believed that the guidelines for case classification and schedule in the current RASR strategy were well-suited to existing national health system and infrastructure as well as the socio-cultural backgrounds.

Challenges for successful implementation of RASR strategy

Although the RASR strategy is acceptable and feasible to implement generally, and many of the survey participants (63%, 50/80) reported that there was no barrier to follow the guidelines of RASR activities, there were some barriers to its implementation. Poor mobile phone connection and internet access were the main barriers to timely case notification (65%, 52/80), case investigation (39%, 31/80) and focus investigation (20%, 16/80). In addition, poor community participation (51%, 41/80) and transportation difficulties (28%, 22/80) were the most cited challenges in carrying out RACD (Table 4). The COVID-19 pandemic also had impact on implementation of the RASR strategy (45%, 36/80) (Additional file 3, Supplementary Table 12). The survey results were supported by qualitative findings which identified two primary categories of obstacles to RASR strategy: health system challenges such as limitations in human and financial resources, and operational challenges such as COVID-19 pandemic, poor community participation, migration of people, telecommunication problems, and transportation difficulties.

Health system challenges

In contrast with malaria supervisors from FGDs who cited having enough human resource as an enabler, a malaria stakeholder in IDI pointed out that human resource shortages at the health centres were a challenge for successful implementation of RASR activities. The health centre staff were responsible not only for malaria but also for other disease programs, and thus, one staff had to work on multiple tasks simultaneously. Heavy workload at the commune level led to delays in completing the RASR activities. Additionally, the IDIs revealed that some VMWs did not have adequate technical knowledge. They could not carry out malaria testing and complete the required documentations because of their limited knowledge on the subject matter and information technology.

Malaria supervisors and VMWs reported in FGD that financial support they received was not enough to conduct RASR activities especially for screening all the suspected households around the index case’s residence during RACD. Furthermore, the VMWs and MMWs were only rewarded with minimal incentives, receiving only three United States dollars per malaria case reported, but no incentive for negative RDT tests conducted. Additionally, increasing costs of gasoline and motorcycle maintenance required for travelling to the remote villages were not covered by the Programme. Besides, VMWs and MMWs had to work to earn a living, occasionally resulting in less effort with RASR activities.

“When a malaria case is detected in a community, it requires investigating and screening the population surrounding the index case. The challenge is insufficient budget to do so.” (A malaria stakeholder in FGD, Ratanakiri province)

Operational challenges

FGDs revealed that community members were confusing between COVID-19 and malaria screenings, and this made RASR activities difficult to implement. Some community members were afraid of COVID-19 infection and refused to meet the malaria programme stakeholders conducting RASR activities. Due to COVID-19 control measures, RASR activities could only be implemented among the malaria high-risk groups because of resources limitation and social distancing.

Poor community participation was identified as a significant obstacle to RASR activities during FGDs and IDIs. Reaching all individuals eligible for RACD was challenging because they worked in remote areas such as forests or farms. VMWs and MMWs could not follow them to their worksites and had to wait for their return, causing significant delays in completing RASR activities. Additionally, the lack of cooperation from some local authorities significantly impacted the malaria programme stakeholders’ ability to announce, communicate and conduct RASR activities in the communities.

“During reactive case detection, the people to be screened (for malaria) are often not at home as they are working in their farms or forests from morning until evening.” (A malaria stakeholder in IDI, Stung Treng province)

According to IDIs, unpredictable mobility patterns of MMPs made mapping their location in conducting RACD and contacting them for treatment difficult, hindering completion of RASR activities in time. Furthermore, the lack of information on the size of MMP population challenged malaria testing and treatment and distributing mosquito net. Additionally, many MMPs had poor malaria knowledge and disregarded RASR activities resulted in refusing to cooperate with screening efforts. This, coupled with the lack of support from employers of MMPs, made screening at the workplace even more difficult.

“Challenges in implementing RASR activities among MMPs include difficulty in carrying out active case detection due to their rapid displacement. Monitoring treatment and drug distribution before they enter into forest are also challenging.” (A malaria stakeholder in IDI, Stung Treng province)

FGDs also highlighted difficult transportation that hindered the timely execution of RASR activities. The poor road conditions in malaria-endemic remote areas made it difficult to travel by motorbike to conduct RASR activities. It was more common during the rainy season when flooding was common, and motorbikes broke down frequently. It made the health personnel’s travelling time longer resulting in delayed RASR activities.

“In remote areas, the condition of the roads can be a significant challenge for us, particularly during the rainy season. During this time, even a short distance of 5-10 km can become a long journey taking 1 to 2 hours to drive.” (A malaria programme stakeholder in FGD, Ratanakiri province)

Moreover, limited mobile phone and internet signals at malaria endemic areas was a major barrier to timeliness of RASR activities, especially case notification. The loss of internet connection caused errors while reporting malaria cases to the Malaria Information System, rendering case notification incomplete. As a result of the limited mobile phone network, malaria cases had to be reported on the second day of diagnosis, resulting in delayed case notification.

“In areas where mobile phone network is unavailable, such as in some villages and farms, it can be challenging for VMWs to contact cases or notify positive cases to the programme staff.” (A malaria stakeholder in IDI, Ratanakiri province)