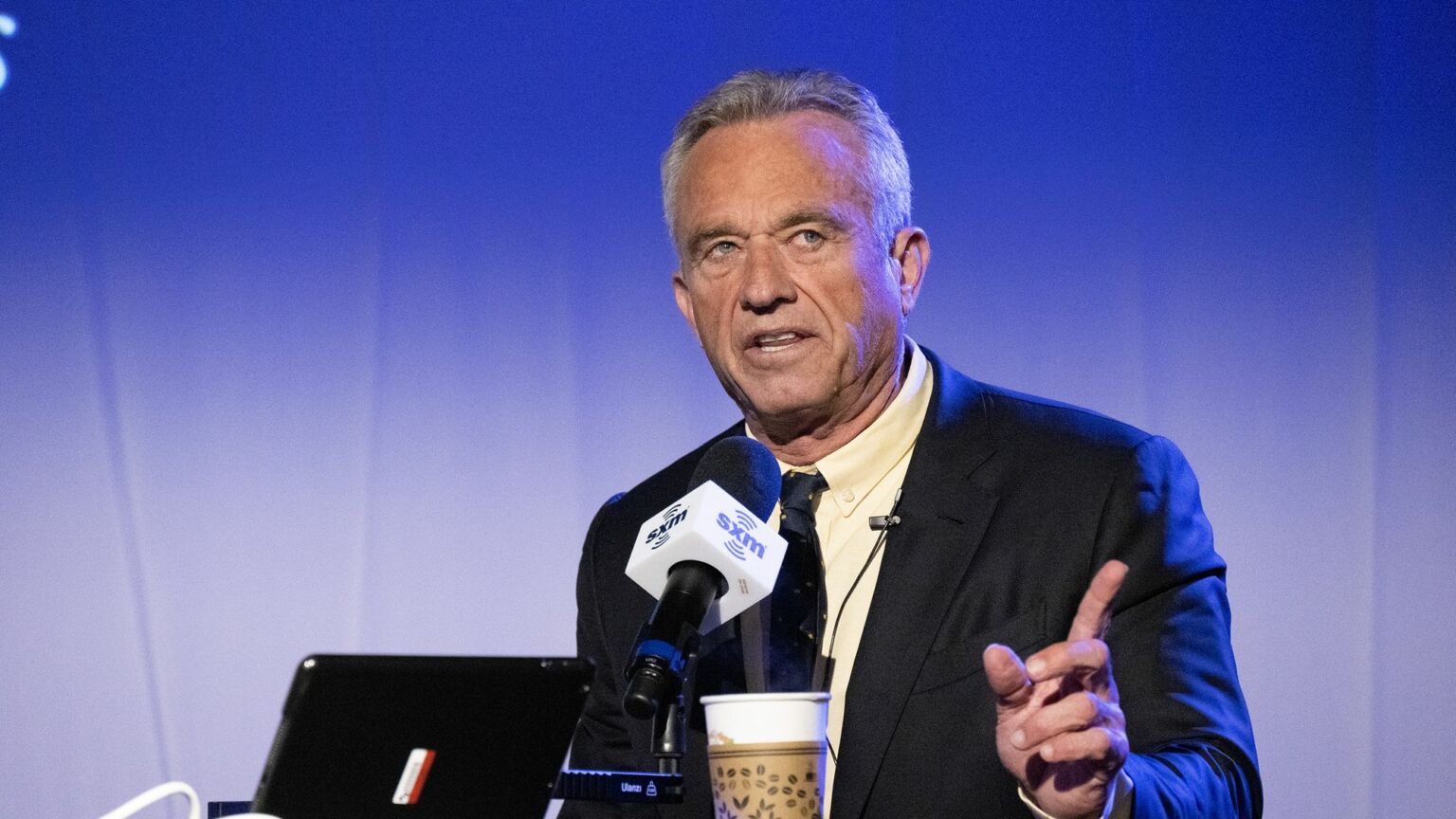

There have been countless reports recently warning of the ‘explosion’ of various forms of cancer among young(ish) people. Prompted by research documenting the rising rate of cancer diagnoses among people under 50, media outlets and politicians, from the Guardian and the BBC to RFK Jr, have been eagerly speculating and fearmongering about the likely causes.

What’s often missing from this discussion, however, is the crucial context of year-on-year improvements in cancer incidence and mortality, and substantial declines in the age-standardised death rates. Among people of the same ages, the cancer mortality risk has fallen by about one-third since 1990.

Collectively, the evidence suggests that true increases in early-onset cancers, especially gastrointestinal cancers and breast cancer, are real, but they still account for only around 10 per cent of all cancer diagnoses. The remaining 90 per cent occur in people over 50. Early-onset cancers are certainly distressing, not least because of the emotional toll, protracted treatment and associated side effects like infertility. But their public-health significance depends not just on how serious they are, but also on how many people they affect.

Plenty of causes have been proposed for the uptick, but the usual suspects dominate: rising levels of obesity, excess alcohol consumption, lack of exercise and poor sleep. In the US, obesity roughly doubled from the early 1990s to 2017. That timing makes for an awkward fit: today’s 30- to 50-year-olds were largely too old to have grown up during the peak of that surge, and most cancers – especially solid tumours like those in the gastrointestinal tract – have long latency periods. Even if we were to assume obesity is the cause, that still leaves many other early-onset cancers unaccounted for. Gastrointestinal cancer represents only about 10 per cent of the increasing cancer incidence. The rest includes cancers like thyroid, testicular and melanoma, which have no strong lifestyle links.

Then there are many other possible causes to explore. Rising parental age, increased childlessness and reduced breast feeding may shape early-life biological risk and contribute to an increased incidence of breast cancer in women. There is ongoing speculation about the role of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, antibiotics and other environmental exposures. There is also the intriguing possibility that the sharp decline in smoking means those genetically predisposed to cancer are not developing typical smoking cancers, but other forms, such as gastrointestinal cancer.

Of course, the expanded use of screening – alongside broader access to healthcare, insurance and routine checks – inevitably leads to more cancers being caught earlier. The fact that mortality remains flat even as incidence rises supports the idea that overall, we’re seeing more diagnosis, not more disease.

It is an entirely reasonable endeavour to try to reduce all incidences of cancer, but there are limits to what current public-health advice can achieve. Even if everyone ate mostly plants, drank little or no alcohol, exercised daily and slept soundly, cancer incidence might drop by 30 to 50 per cent at most. That is because the modifiable risk factors, while not irrelevant, aren’t especially powerful.

Obesity is associated with a two- to four-fold increase in the risk of developing certain cancers – most notably endometrial, esophageal, colorectal, kidney and postmenopausal breast cancer. For most cancer types, however, the increased risk associated with obesity is below two-fold. Far more impactful is excessive alcohol consumption, which roughly doubles the risk of liver and esophageal cancers, and increases breast and colorectal cancer risk by 30 to 60 per cent. Even these numbers pale in comparison with smoking. Smoking increases the lifetime risk of lung cancer by about 25 times, doubles the risk of serious illness in middle age and triples or quadruples the risk of fatal cancers overall. The effects of other lifestyle factors, like sleep, stress and physical inactivity – which increasingly crop up in cancer-related headlines – are very small.

It is morally dubious to give the impression that one’s health is entirely under one’s personal control because (with the exception of chronic smoking) it isn’t. More than that, trying to optimise your health above all else often means giving up the kind of life most people actually want to live. If you find joy in military-grade dietary discipline, precision-tuned workouts and lifelong abstinence, then fine – you might gain an extra two to four years of life. But scaring people into conformity because of a modest rise in early cancer is unreasonable.

Yet that’s exactly where some interventions courted by healthcare bodies are headed. The ‘health belief model‘, for example, urges people to see themselves as high-risk and to absorb that risk as a personal concern. This way, they can be more readily nudged into preventative health behaviours. Applying that logic to adolescents means fuelling fresh anxieties in a generation already spooked by crime, climate collapse and economic doom.

For years, the medical authorities have inflated health risks beyond proportion, fuelling an unhealthy obsession with staying well. But health at all costs is too high a price. It’s frankly anti-social to stoke panic over a modest rise in early-onset cancers just to herd everyone under 30 into bland diets, joyless workouts, routine screenings and a state of constant bodily surveillance. That’s not healthy living, it’s lifestyle asceticism for zealots. Most people accept a little risk in exchange for a life that’s actually worth living. What they reasonably reject is misery now in return for a few extra years at the end – years that are never guaranteed to be gained and are always guaranteed to end.

Stuart Derbyshire is an associate professor of psychology at the National University of Singapore.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!