This prospective observational cohort study provides critical insights into the complex interplay between salt restriction, nutritional status, sarcopenia, and mortality in cirrhotic patients with grade III ascites. Our findings challenge the conventional paradigm that strict dietary sodium restriction is universally beneficial for ascites management. Instead, our results suggest that while sodium restriction may theoretically reduce fluid retention, it is associated with significant adverse effects, including higher mortality rates, increased prevalence of sarcopenia, and poorer nutritional status. These findings align with emerging literature questioning the indiscriminate application of sodium restriction in cirrhotic patients and highlight the need for a more nuanced, individualized approach to dietary management [18].

Malnutrition is a well-recognized complication in patients with cirrhosis, with prevalence rates reaching up to 80% [5]. Protein-energy malnutrition, compounded by increased metabolic demands and anorexia, is exacerbated by excessive sodium restriction, as demonstrated in our study. One of the most striking findings was the significant increase in nutritional risk among patients on a salt-restricted diet. Patients in the SRD group had a higher proportion of high nutritional risk (58.1%) than those in the SUD group (41.9%) (p = 0.001). The logistic regression analysis revealed that SRD was an independent predictor of high nutritional risk (OR = 0.129, p = 0.004). This suggests that excessive sodium restriction may contribute to insufficient caloric and protein intake, leading to muscle wasting. Similar findings were reported by Sorrentino et al., emphasizing that restricting sodium without compensatory nutritional strategies may lead to deterioration in muscle and protein stores [19].

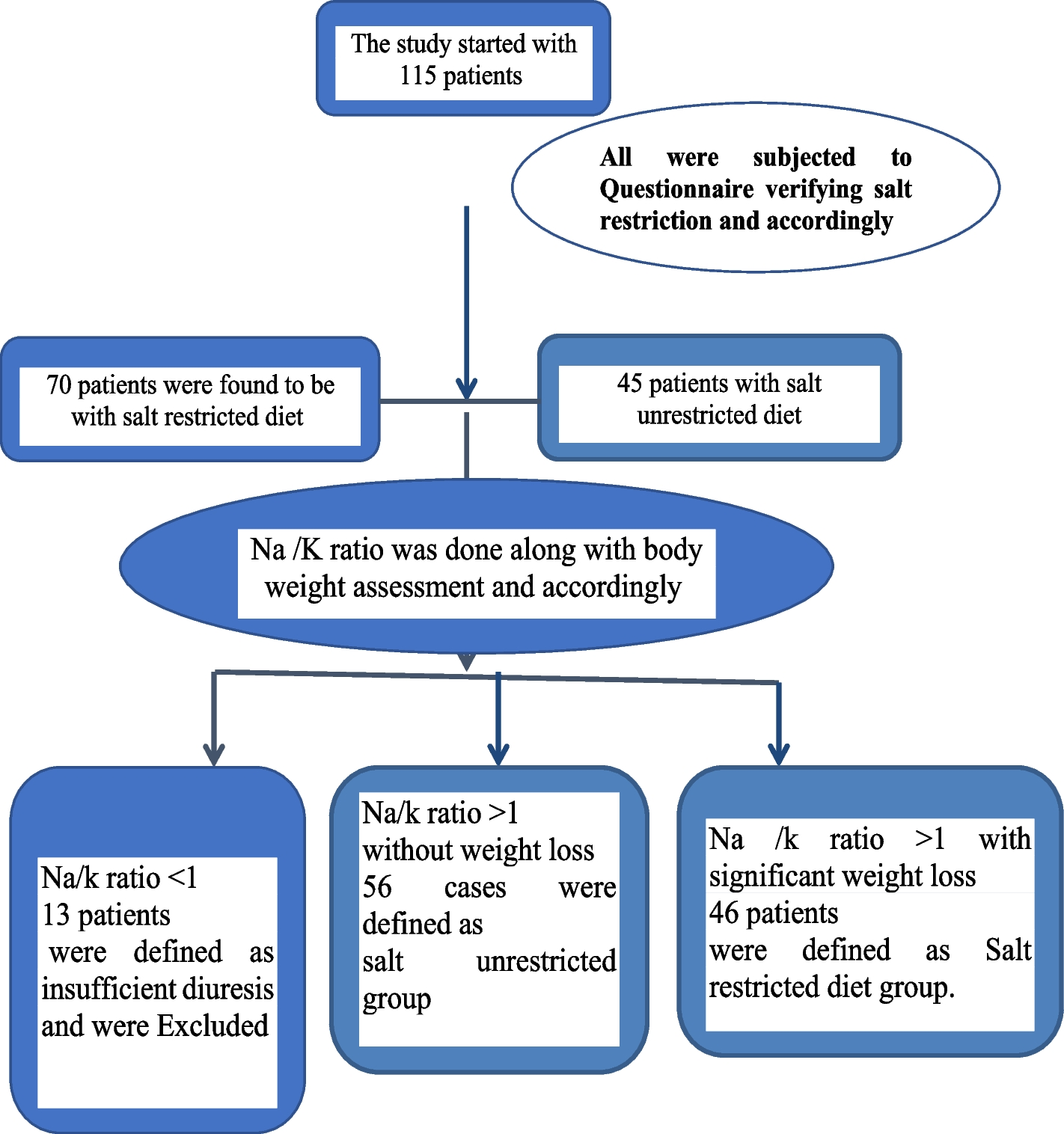

Few studies, with varying methodological quality and inconsistent findings, have examined the effects of salt restriction on nutrition in patients with cirrhosis. Soulsby et al. found that patients without salt restrictions experienced reduced ascites, better nutritional status, and shorter hospital stays [20]. Similarly, Gu et al., in the largest study to date, randomized 200 patients with ascites into unrestricted (8.8 g NaCl) and restricted (4.2 g NaCl) sodium groups, finding that the unrestricted group experienced better renal function, higher calorie intake, increased serum albumin, and shorter hospital stays, along with greater ascites resolution (P = 0.001) [21]. Similarly, Sorrentino et al. observed that the sodium-restricted group required paracentesis more frequently and had higher mortality rates [19]. Morando et al. in a study of 120 outpatients, noted that in the salt-restricted diet group (4.6 g NaCl/day) there was reduced caloric intake by 20%, with only 30.8% adhering to the diet. Many patients misunderstand their sodium intake levels, likely due to inadequate dietary guidance, leading some to unintentionally lower their calorie intake to reduce salt intake [22].

The present study highlights the critical role of sarcopenia in cirrhotic patient outcomes. Sarcopenia was significantly more prevalent in the SRD group (p < 0.006), with a lower skeletal muscle index (SMI) and trunk protein muscle mass (TR PMM). More importantly, sarcopenia was an independent predictor of mortality (OR = 2.684, p = 0.02) in our multivariate analysis. These findings corroborate previous reports by Montano-Loza et al. and Kalafateli et al., who identified sarcopenia as an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in cirrhotic patients [23, 24].

The lower PMM in the SRD group may stem from dietary restrictions and cirrhosis-related catabolism, whereas fluid overload in the SUD group may artificially inflate PMM readings because increased extracellular fluid can distort body composition. It is likely that the results of a small study by Soulsby et al., who reported reduced dry body weight and mid-arm muscle circumference over four weeks on a low-sodium diet, although this timeframe is too brief to assess long-term impacts [19]. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this association likely involve increased catabolism due to inadequate protein intake, loss of muscle mass secondary to sodium restriction-induced metabolic alterations, and impaired nitrogen balance [25].

The primary rationale for sodium restriction in cirrhosis is to reduce fluid retention and decrease the need for paracentesis [26]. This study data suggests that sodium restriction was necessarily translated into superior ascites control.

Remarkedly, the SUD group showed significantly higher modified weight than in the SRD group (p = 0.001). Total body water (TBW) was also significantly higher in the SUD group (mean 40.31 ± 12.08) than in the SRD group (mean 33.84 ± 6.86, p < 0.001), which could indicate that patients on an unrestricted diet retained more fluid, leading to higher TBW. Water retention increases body weight without necessarily reflecting improved nutritional or muscle status, as it primarily represents extracellular fluid accumulation [27, 28].

Hence, these results demonstrate that salt restriction significantly improves ascites control, and the regression analysis confirmed that SRD was an independent predictor of improved ascites control (OR = 2.461, p < 0.001). These findings align with previous studies supporting sodium restriction as a fundamental component of ascites management. However, our study suggests that while ascites control is enhanced, it comes at the cost of worsening nutritional status, warranting careful dietary adjustments.

Contradictory, was the observation reported by Ruiz-Margáin et al., who noted that a less restrictive sodium approach did not worsen ascites control but improved nutritional outcomes in cirrhotic patients [29].

While paracentesis frequency is a widely used marker for ascites control, it does not fully capture the complex interplay of fluid balance, nutritional status, and renal function in cirrhotic patients. To address this limitation, our study also considered changes in body weight, TBW measured by BIA, and serum sodium levels as additional markers of ascites management. Our results indicate that patients in the SRD group exhibited lower TBW and required fewer paracenteses, suggesting better ascites control. However, the significant weight loss observed in the SRD group raises concerns about nutritional depletion and potential muscle loss due to excessive sodium restriction. These findings mirror similar results in literature. For instance, Gu et al. and Sorrentino et al. reported that patients following a less restrictive sodium regimen had better nutritional outcomes, including higher caloric and protein intake, which contributed to improved ascites control and reduced need for paracentesis [20, 21]. Bernardi et al. also highlighted that excessive sodium restriction can exacerbate malnutrition and muscle wasting, ultimately leading to more frequent ascites’ recurrence [24]. These findings highlight the delicate balance between sodium restriction, fluid management, and nutritional status in cirrhotic patients. Future studies should integrate longitudinal assessments of ascitic fluid volume, renal function, and body composition to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of ascites control in response to dietary interventions.

One of the most striking findings of our study is the significantly higher mortality rate in the SRD group (67.4%) compared to the SUD group (35.7%, p = 0.001). This association persisted after adjusting for confounders, with logistic regression confirming salt restriction as an independent predictor of mortality (OR = 3.72, 95% CI: 1.63–8.48, p = 0.002). This raises important concerns regarding the conventional wisdom advocating for stringent sodium restriction in cirrhotic patients with ascites. Previous studies have reported conflicting results regarding the impact of sodium intake on mortality. Pashayee-Khamene et al. found that moderate sodium restriction, rather than severe limitation, was associated with improved survival in cirrhotic patients [30]. In contrast, Sorrentino et al. demonstrated that patients on a strict salt-restricted diet without nutritional support had a 3.9-fold higher risk of mortality within one year [21]. Our findings align with these studies, reinforcing the notion that excessive sodium restriction may have unintended deleterious effects on patient survival.

A balanced dietary approach is essential for cirrhotic patients to mitigate the nutritional risks of salt restriction, including muscle loss and malnutrition. Adequate protein intake (1.2–1.5 g/kg/day), high-quality protein sources, and BCAA supplementation help preserve muscle mass, while frequent meals and bedtime snacks counteract catabolism. Moderate sodium restriction (5–7 g salt/day) optimizes ascites control without causing excessive volume contraction or hyponatremia. Additionally, potassium-rich foods and calcium/vitamin D supplementation support electrolyte balance and bone health. Future research should explore structured nutritional interventions to enhance both ascites management and overall nutritional outcomes.

This study has several strengths, including its prospective design, which allows for a more accurate assessment of dietary sodium adherence and its effects on clinical outcomes compared to retrospective analyses. The comprehensive evaluation of multiple clinically relevant endpoints, such as sarcopenia, nutritional status, and mortality, provides a holistic understanding of sodium restriction’s impact on cirrhotic patients. Additionally, the use of validated methodologies, including the Royal Free Hospital-Nutritional Prioritizing Tool (RFH-NPT) for nutritional assessment and bioelectrical impedance analysis for sarcopenia evaluation, strengthens the study’s reliability. The sample size was adequate for detecting significant differences in mortality and sarcopenia, as confirmed by post hoc power analysis, ensuring robustness in the findings.

However, there are limitations to consider. Being a single-center study, the generalizability of the findings to broader populations may be limited. Furthermore, while baseline sarcopenia was assessed, the absence of serial sarcopenia measurements precludes the evaluation of its progression over time. Lastly, the six-month follow-up period, though adequate for short-term mortality and nutritional impact evaluation, does not account for long-term outcomes related to sodium intake, necessitating further longitudinal studies.

Our study underscores the need for an individualized, patient-centered approach to dietary sodium management in cirrhotic patients. Rather than a blanket recommendation for strict sodium restriction, a tailored approach that considers each patient’s nutritional status, sarcopenia risk, and fluid balance is warranted. Future multicenter, randomized controlled trials are necessary to refine sodium intake recommendations and develop evidence-based dietary guidelines that optimize both ascites control and nutritional status.