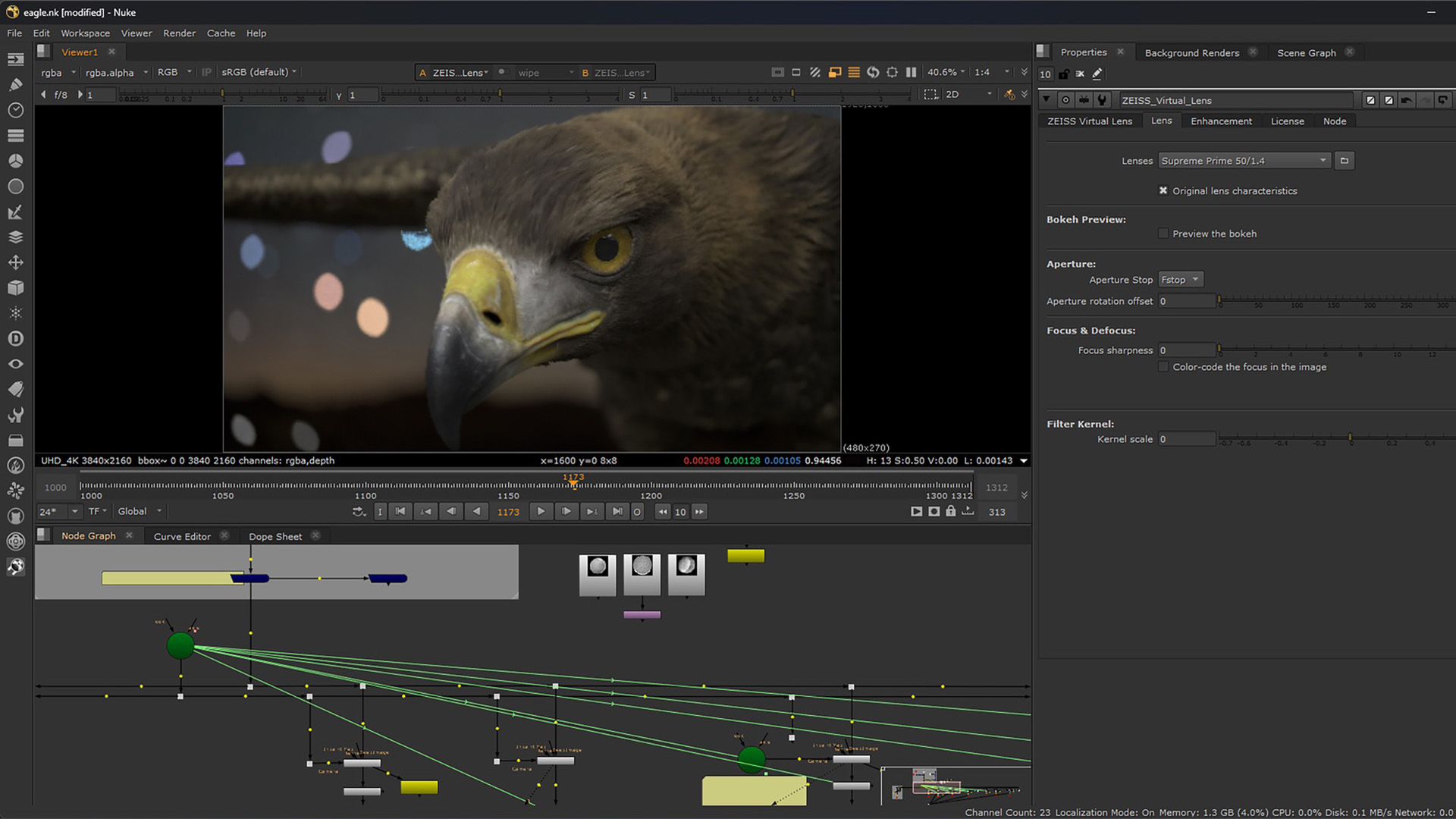

ZEISS is inviting VFX artists to register for a closed beta of CinCraft Virtual Lens Technology, a Nuke plugin that simulates real-world lens behavior inside 2D compositing. The three-month program is set for December 2025 through February 2026,…

ZEISS is inviting VFX artists to register for a closed beta of CinCraft Virtual Lens Technology, a Nuke plugin that simulates real-world lens behavior inside 2D compositing. The three-month program is set for December 2025 through February 2026,…