Table 1 presents differences in characteristics for those who reported losing and adopting foods after migration. Those who reported no longer consuming at least one type of food after migration were different from those who reported that they still ate all of the same items in terms of region of origin, economic standing, age, education, region of residence, years in the US, marital status, school children living at home, English fluency and visa type. Those who reported eating some new foods after migration were different from those who didn’t in terms of region of origin, economic standing, age, education, region of residence, years in the US, marital status, school children living at home, English fluency, and visa type.

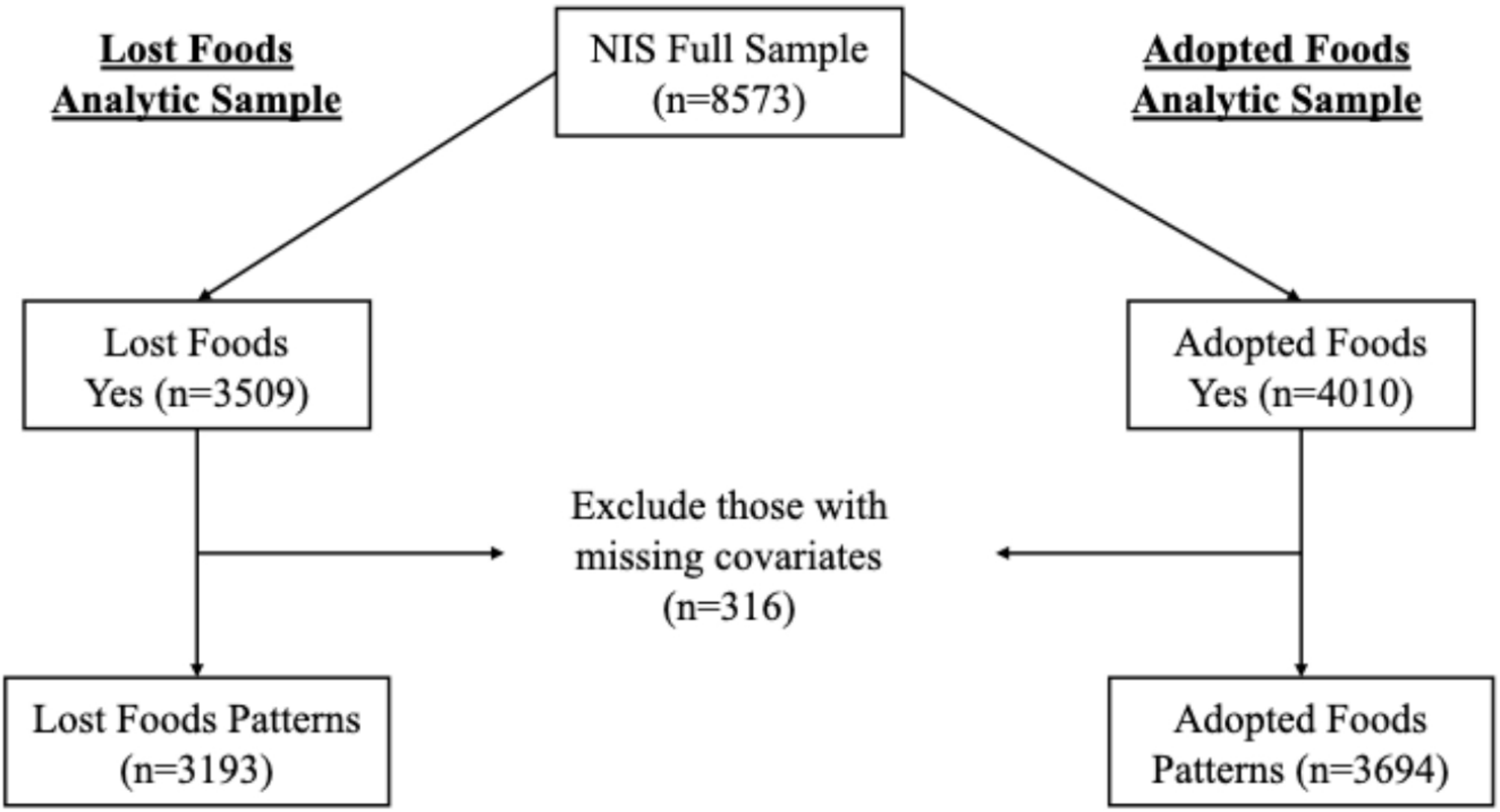

Those who reported losing or adopting foods listed on average 3.5 foods that they no longer consumed and 3.2 foods that they started consuming after migration. Figure 2 lists foods no longer consumed in the US (lost) and foods newly consumed in the US (adopted). The most often reported lost food items were “ethnic foods” (21.9%) and vegetables (16.2%); the most often reported adopted food items were red (18.5%) and processed meats (17.2%).

Food groups no longer consumed in the US

PCA scree plots and eigenvalues composed of foods no longer eaten in the US indicated that a three- to six-factor solution was the best fit to the data. PCA for foods no longer eaten in the US stratified by years in the US and gender had excellent to acceptable fit for the three-factor solution (Appendix Table 2). A three-factor solution for foods no longer eaten in the US combined by gender and years in the US was selected as the most meaningful.

We assigned names to food patterns based on the positive factor loadings that contributed most to each pattern (≥0.20) Component 1: home country foods; Component 2: protein & whole grains; Component 3: meat & vegetables (Fig. 3, Panel A). 21% of the variance was explained with a three-factor solution. The home country foods pattern comprised of “ethnic foods” (includes items such as “bread from my home country, ethiopian bread, etc”), cheese, and refined grains with high negative loadings for fish, fruit and vegetables. A high negative loading for a food group means individuals that had listed food groups like “ethnic foods”, cheese, and refined grains were less likely than the overall sample to report losing foods such as fish, fruits and vegetables. The protein & whole grains pattern comprised of soup, whole grains, eggs, poultry, and beans/nuts/legumes/seeds with high negative loadings for chips/snacks, sweets, ethnic foods, and fruit. The meat & vegetables pattern comprised of fats, fish, eggs, poultry, red meat, and vegetables, with high negative loadings for whole grains and beans/legumes/nuts/seeds.

Lost and Adopted Food Group Factor Loadings derived among Foreign-Born Adults who Achieved Legal Permanent Residency in 2003 in the US. Panel (A) Lost Foods. Panel (B) Adopted Foods- Men. Panel (C) Adopted Foods- Women. Note: Lost: The 3-factor solution resulted in 21% of the variance; Adopted: The 3-factor solution resulted in 36% of the variance explained for both males and females Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (kmo) statistics: (Lost: 0.50); (Adopted: [male (0.62); female (0.65)]). Lost: Sample Size n = 3,509; Adopted: Sample Size [male (n = 1995); female (n = 2015)]

Patterns of foods no longer consumed in the US

Table 2 shows associations of individual covariates with the three lost food patterns described above. Note that in interpretation of estimates from the models of lost food patterns, a positive estimate means higher reporting of a lost food pattern and a negative estimate means lower reporting of a lost food pattern.

Individuals from East and South Asia and Europe were more likely to report losing foods in the meat & vegetables pattern [β (95% CI)]; [Component 3: Those from East & South Asia (0.19 [0.06,0.33]); Europe (0.28 [0.13,0.43]] and Europe were also more likely to report losing foods within the home country foods pattern [Component 1: (0.29 [0.12,0.47])] compared to those from Latin America. Men were less likely to report losing foods within the protein & whole grains pattern [Comp 2: -0.18 (-0.28,-0.08)] than women. Those with more education were less likely to report losing foods within the protein & whole grains pattern [Component 2: -0.01 (-0.03,-0.0008)]. Those currently living in the Western US were more likely to report losing foods within the home country foods pattern [Component 1: 0.22 (0.07,0.37)] compared to those who were living in the Southeast. Those who had lived in the US for longer were more likely to report losing foods within the home country foods pattern [Component 1: 0.01 (0.002,0.02)]. Those who migrated to the US on an employment visa were more likely to report losing foods within the home country foods pattern [Component 1: 0.17 (0.02,0.33)] compared to those who migrated on a family reunification visa.

Food groups consumed in the US

PCA scree plots and eigenvalues composed of foods adopted after coming to the US suggested that a three- to six-factor solution was the best fit to the data. PCA for foods adopted in the US stratified by years in the US revealed excellent to acceptable fit for the three factor solution. However, PCA adopted foods stratified by gender revealed a congruence coefficient below the threshold of 0.50, meaning the patterns for men and women are not similar enough to combine and we kept a 3-factor solution for adopted foods stratified by gender (36% of variance for both men and women) (Appendix Table 2).

For men, the names assigned based on the 3-factor solution and the factor loadings were: [Component 1: junk food; Component 2: meat (red and processed) and refined grains; Component 3: “ethnic” & refined grains]. (Fig. 3, Panel B). The junk food pattern comprised of pizza and processed meats, with a high negative loading for red meat. The meat & refined grains pattern comprised of processed meats, refined grains, and red meat with high negative loadings for fruits and vegetables. The “ethnic” & refined grains pattern comprised of “ethnic” (including soups) and refined grains with high negative loadings for pizza, processed meats, red meat, and fruits.

For women, (Fig. 3, Panel C), components explained 36% of the variance with a 3-factor solution [Component 1: fruits & vegetables; Component 2: red meat & poultry/eggs; Component 3: meat (red & processed) & fruits]. The fruits & vegetable pattern was comprised of fruits and vegetables with high negative loadings for pizza and processed meats. The red meat & poultry/eggs pattern was comprised of red meat and poultry/eggs with high negative loadings for processed meats and fruit. The meat & fruit pattern was comprised of processed meats, red meat, and fruit with a high negative loading for vegetables.

Patterns of foods consumed in the US

Men from Europe, Central Asia, Canada regions were less likely to report adopting foods within the junk foods pattern and the meat & refined grains [Components 1: -0.10 (-0.17,-0.02); Component 2: -0.18 (-0.25,-0.11)] compared to those from Latin America and the Caribbean (Table 3). Men who lived in rural areas compared to urban areas before migration were less likely to report adopting foods within the junk foods pattern and “ethnic” & refined grains pattern [Components 1 & 3] [Component 1: -0.06,-0.12,-0.003)]; Component 3: -0.07 (-0.11,-0.02)]. Men living in the Midwest, Northeast, and Western regions of the US were more likely to report adopting foods within the junk foods pattern [Component 1] compared to those living in the Southeast region [Midwest: 0.14 (0.06,0.23)]; [Northeast: 0.08 (0.01,0.15)]; [West: 0.11 (0.03,0.18)]. Men living in the Northeast were less likely to report adopting foods within the meat & refined grains pattern [Component 2] [-0.08 (-0.15,-0.02)]. Men who had come to the US on refugee visas were less likely to report adopting foods within the three components compared to men who arrived on a family reunification visas [Component 1: -0.14 (-0.23,-0.04]; [Component 2: -0.09 (-0.17,-0.0009)]; [Component 3: -0.12 (-0.18,-0.06)].

Women from East and South Asia and Europe were more likely to report adopting foods within the fruits & vegetables pattern [Component 1] compared to those from the Latin America and Caribbean region (Table 3) [East and South Asia: 0.11 (0.05,0.18)]; [Europe: 0.25 (0.17,0.32)]. Women from Middle East and North Africa were less likely to report adopting foods within the meat & fruit pattern [Component 3: -0.11 (-0.18,0.01)] compared to those from Latin America and Caribbean region. Women living in the Northeast were less likely to report adopting foods within the red meat & poultry/eggs pattern [Component 2] compared to women living in the Southeast [-0.09 (-0.15,-0.04)]. Women who had lived in the US for longer were less likely to report foods within the meat & fruit pattern [Component 3: -0.003 (-0.0005,-0.002)]. Women who had obtained a legalization visa in 2003 were more likely to report adopting foods in line with fruits & vegetables pattern [Component 1: 0.09 (0.006,0.17)] and red meat & poultry/eggs pattern [Component 2: 0.13 (0.06,0.22)] compared to those with a family reunification visa.