The most commonly endorsed barriers amongst non-attending women responding to our survey were difficulties making a convenient appointment close enough to home, worry about and/or previous experience of pain, concern that a man would do the test and having too many other things to worry about. In particular, pain (worry about pain and/or previous experience of pain) was a markedly prominent barrier, endorsed by nearly 40% of participants. These barriers are similar to those identified in the recent Cancer Awareness Measure (CAM) survey [4] where appointment convenience and locality, pain, concerns about a man doing the screening test and having too many other things to worry about also featured within the most endorsed barriers among screening attenders as well as non-attenders. Endorsement of the barriers by non-attenders (N = 91) in the CAM survey ranged between 9 and 19% which was lower than for this study and may reflect the different sampling methods (direct contact with non-attenders vs. a population-based survey including only a small proportion of non-attenders).

Exploration of the free text responses provided additional insight into barriers faced by participants. The high volume of free text responses was unanticipated, and it was interesting that women used this space as a forum to express their concerns and experiences about screening in more detail. A substantial proportion elaborated on experiences or fears about pain. This corresponds with both the findings of this study and existing quantitative and qualitative research illustrating that pain represents a particularly powerful barrier to different types of cancer screening [16,17,18]. The free text responses also revealed additional barriers, the most common of which were work commitments, difficulties with appointment communication and previous negative experience of screening. These are closely aligned with the pre-defined barriers of appointment convenience, pain and embarrassment and highlight the salience of issues around accessibility and acceptability.

Most women reported multiple barriers to breast screening which often encompassed facets of individual belief (e.g. worry about screening being painful) and motivation to attend screening (e.g. beliefs about having other more important things to do) as well as wider organisational and opportunistic barriers s (e.g. not being able to find a local appointment). These findings highlight the multifaceted causation of screening non-attendance and are consistent with the COM-B (Capability Opportunity Motivation– Behaviour) framework of health behaviour [19] which conceptualises screening behaviour as the product of an individual’s capability, motivation and opportunity to attend screening. This suggests that multi-component interventions that tackle a variety of barriers spanning individual beliefs around capability and motivation as well as addressing service-level barriers facilitating the opportunity to attend may be most useful to increase participation.

Exploratory analysis indicated variations in barrier endorsement according to several demographic factors. Age was found to have a significant influence on barrier endorsement. Women aged ≤ 64 reported greater difficulties getting a convenient appointment which may reflect greater demands on their time particularly from work. Older women were more likely to report previous experience of pain as a barrier, consistent with their greater breast screening experience. Prior experience of pain during breast screening is a significant predictor of expectation of pain at future breast screening and is significantly associated with reduced reattendance [18].

Age was also associated with concern that a man may conduct the mammogram with women aged between 55 and 64 more likely to endorse this barrier than younger or older women. There is no clear explanation for this finding. It may be spurious due to multiple testing in exploratory analysis but merits further research. Women from minoritised ethnic backgrounds and those who reported mental health problems were also more likely to be concerned about a man doing the mammogram. Mammography is the only health procedure conducted exclusively by women practitioners with employers allowed to restrict mammography roles to females only within current equality legislation. The NHS breast screening invitation states that “Female staff will take your mammograms” and the accompanying leaflet states that “Mammograms are carried out by women called mammographers” and uses she/her pronouns to reference the mammographer as well as using a picture of a female mammographer. However, the findings of our survey and other research suggest this message has not reached all screening invitees [20, 21]. Our finding that women from minoritised ethnic backgrounds were more likely to endorse concern about a man doing the screening test has also been identified in other research and may reflect cultural and religious differences in modesty, acceptability of nudity and perceptions of indecency [20].

In relation to mental health status, research has identified that women with mental health problems or mental illness are less likely to attend breast screening, have poorer cancer outcomes and may have less awareness and understanding of the specifics of the screening process, and may be more likely to avoid medical examinations in general [13, 22,23,24]. It is possible that reduced awareness and understanding may increase vulnerability to the misperception that a man may conduct the mammography. It is important to note that our self-reported measure did not gather specific information about the type or severity of mental health problems, so it is difficult to draw specific conclusions; however, the overall findings suggest that the misperception that a man may conduct the screening is more prevalent amongst women with mental health problems.

The appointment being too far away was more likely to be endorsed by those reporting a physical disability. This finding fits in with previous research illustrating that physical barriers to healthcare including distance to appointments and lack of transport are particularly salient for individuals with disability [25, 26].

It is noteworthy that we did not identify any variation in barrier endorsement according to educational level suggesting that the nature of barriers faced by individuals with different educational backgrounds may not be significantly different. In the context of the robust association between lower educational attainment and lower screening uptake [9], it is possible that this association may be driven more by the additive impact of multiple barriers and lack of resources to overcome those barriers facing those from lower educational backgrounds rather than from variation in the type of barriers faced.

Most respondents reported being aware of breast screening and receiving invitations, however, respondents from minoritised ethnic backgrounds were more likely to indicate lack of awareness of breast screening or report not ever receiving an invitation. This finding aligns with previous research that has identified lower levels of cervical screening awareness and engagement as barriers to uptake amongst minoritised ethnic populations [27]. It is particularly notable that this was the case even in a sample of women who had recently been invited for screening, according to NBSS.

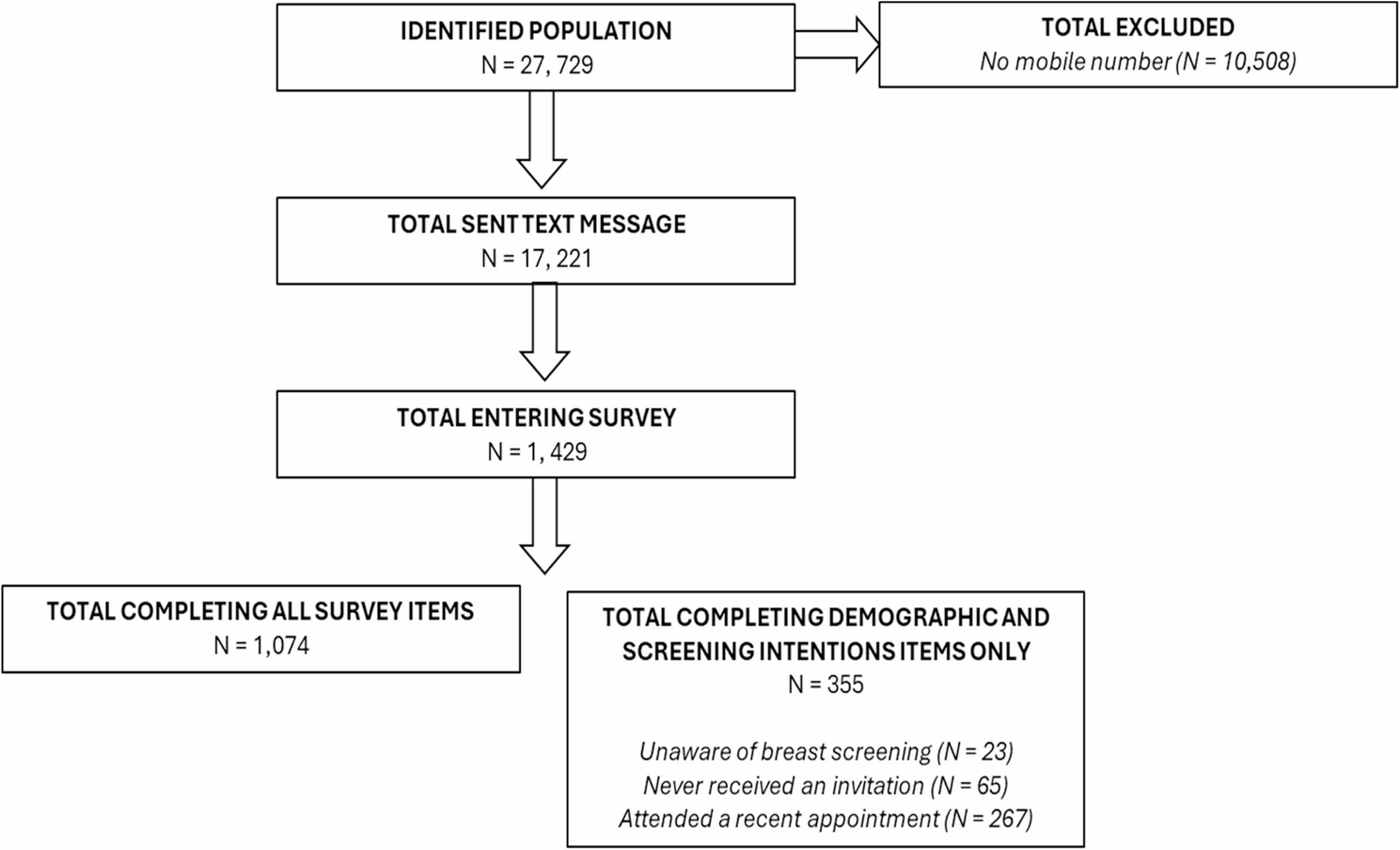

There are several limitations to the survey results. As anticipated, the response rate was very low with only 5.1% of those identified as not attending breast screening entering the survey which limits generalisability of our findings. The low response rate was partially due to the inability to contact over a third of identified participants due to the lack of a recorded mobile phone number. This is an important limitation as the lack of valid mobile telephone numbers recorded in NBSS is not random. Those with no recorded number are likely to be women who have limited contact with their GP, are unregistered with a GP or have no mobile phone access. These women may experience different barriers to the women with recorded mobile telephone numbers and merit further research. The high proportion of women without a mobile number recorded also has implications for the planned shift to digital app-based invitations [28]. Similarly, it was not possible to determine the type of breast screening invitation (timed or open appointment) that participants had received, and it may be that barriers vary by invitation type.

The majority of respondents were aged < 64 which limits generalisability of our findings to older populations whose barriers may differ; however, as attendance has been found to increase with increasing age, this may be a less significant limitation [4]. Furthermore, due to the anonymous nature of the survey, we were not able to use information from screening records in our analysis and subsequently were not able to determine individual screening histories (for example, how many previous appointments had been missed or attended) nor previous screening results or breast cancer diagnoses. Similarly, we asked participants to report whether they had mental health conditions and/or disability using a binary response format, however, we acknowledge that these questions are simplistic and do not capture the different types of mental health conditions and disability that may differentially impact access to screening. More nuanced analysis exploring the barriers faced by individuals with different screening histories, mental health conditions and types of disabilities would provide more specific insight into the barriers encountered by these populations, however, our analysis aimed to provide an overview of the barriers faced by non-attenders as well as exploration of variation in barrier endorsement according to broad demographic variables as a first step to identifying targets for intervention.

Generalisability to all non-attenders is further limited by possible self-selection bias whereby those opting to complete the survey may differ from those who chose not to complete it. Similarly, the survey required participants to recall the barriers preventing them from attending screening and these recollections may be inaccurate and vulnerable to recall bias. We aimed to reduce this risk by only including non-attenders who had been invited for screening within the last six months. In addition, the study was carried out over a 6-month period which means we cannot rule out the possibility that we did not capture seasonal barriers affecting attendance at different times of the year. However, exploration of the free text responses revealed very little mention of seasonal issues (coughs/colds, seasonal busyness or holidays) suggesting that these issues were not significant barriers.

A significant proportion of respondents from minoritised ethnic backgrounds were routed out of the barriers part of the survey because, on entering the survey, they indicated they were either unaware of screening or reported not receiving an invitation. This, combined with the overall small numbers initiating the survey, means that relatively few women from minoritised ethnic backgrounds completed the barriers items, again limiting generalisability. The survey was administered in English only, which limited accessibility for non-English speaking participants. The survey did includ assessment of language and ease of understanding of the invitation which indicated only a small proportion of participants did not speak English and very few reported trouble understanding the invitation. However, respondents with limited English may have found it difficult to complete the survey or may have been routed around this question by indicating lack of screening awareness or invitation receipt at the start of the survey. Older women from minoritised ethnic backgrounds have also been found to have less access to mobile phones and the internet which would have further limited the accessibility of the survey [29]. In the context that screening adherence is typically lower in minoritised ethnic populations [8, 30] further research using more accessible methods is required to clarify the barriers that are most prevalent in these populations.

Despite the low response rate and limited ethnic diversity, the sample size was considerably larger than that included in the CAM survey and provides insight into the barriers faced by an under-researched population.

Our findings have three key implications for increasing breast screening uptake. Firstly, there is a need for appointment booking modernisation and flexibility as the most common barrier to attendance was difficulty getting a convenient appointment. The difficulties associated with competing priorities, locality of appointment and communication around the appointment were also highly endorsed or referred to within the free text responses. Ensuring flexible appointments in local areas that are easy to access and schedule as well as simple to cancel and reschedule would help to overcome this barrier. Secondly, there is a need to communicate even more clearly to women that men will not be conducting their breast screening to reduce this misperception. This could involve adding a direct statement clarifying the female only nature of mammography in the leaflet accompanying the breast screening invitation or may entail exploring different modes of communication from traditional written information, for example, greater use of emphasis and visual images to more clearly disseminate this message. This is a particularly important for equitable access as our findings suggest that this barrier disproportionately impeded women from minoritised ethnic backgrounds and those reporting mental health problems who have lower screening uptake and poorer breast cancer outcomes. It is timely to note here that current shortfalls in mammographer recruitment have led to recent calls to allow men to practice as mammographers; however, our findings suggest that this should be approached with caution and more research is required to determine ways in which this could be addressed sensitively, for example, the use of chaperones or offering choice of practitioner gender. Our findings correspond with the results of recent commissioned work exploring the potential impact of the introduction of male mammographers into the NHS breast screening programme [31].

Thirdly, our finding that both previous experience of pain and fear of pain were significantly endorsed barriers as well as the high volume of free text responses describing painful experiences or significant fear of pain, suggests that tackling pain during breast screening is important to increasing uptake. Pain has been identified as a consistent barrier to screening and has been found to reduce attendance [18, 32]. Little is currently known about ways to prevent or reduce pain during screening and there is a need to address this gap within the research to identify effective ways to make screening more comfortable for women [33].