Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

We enrolled 20 women after EmCS with their age ranging between 16 and 40 years (Table 1). Most women were between 25 and 34 years. Primiparity was the most dominant parity and the commonest indications for surgery were severe hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, obstructed labour, more than two previous caesarean scars and abnormal presentation (Table 1).

We also interviewed six KIs, comprising of two obstetrician/gynaecologists, two senior resident doctors and two senior midwives.

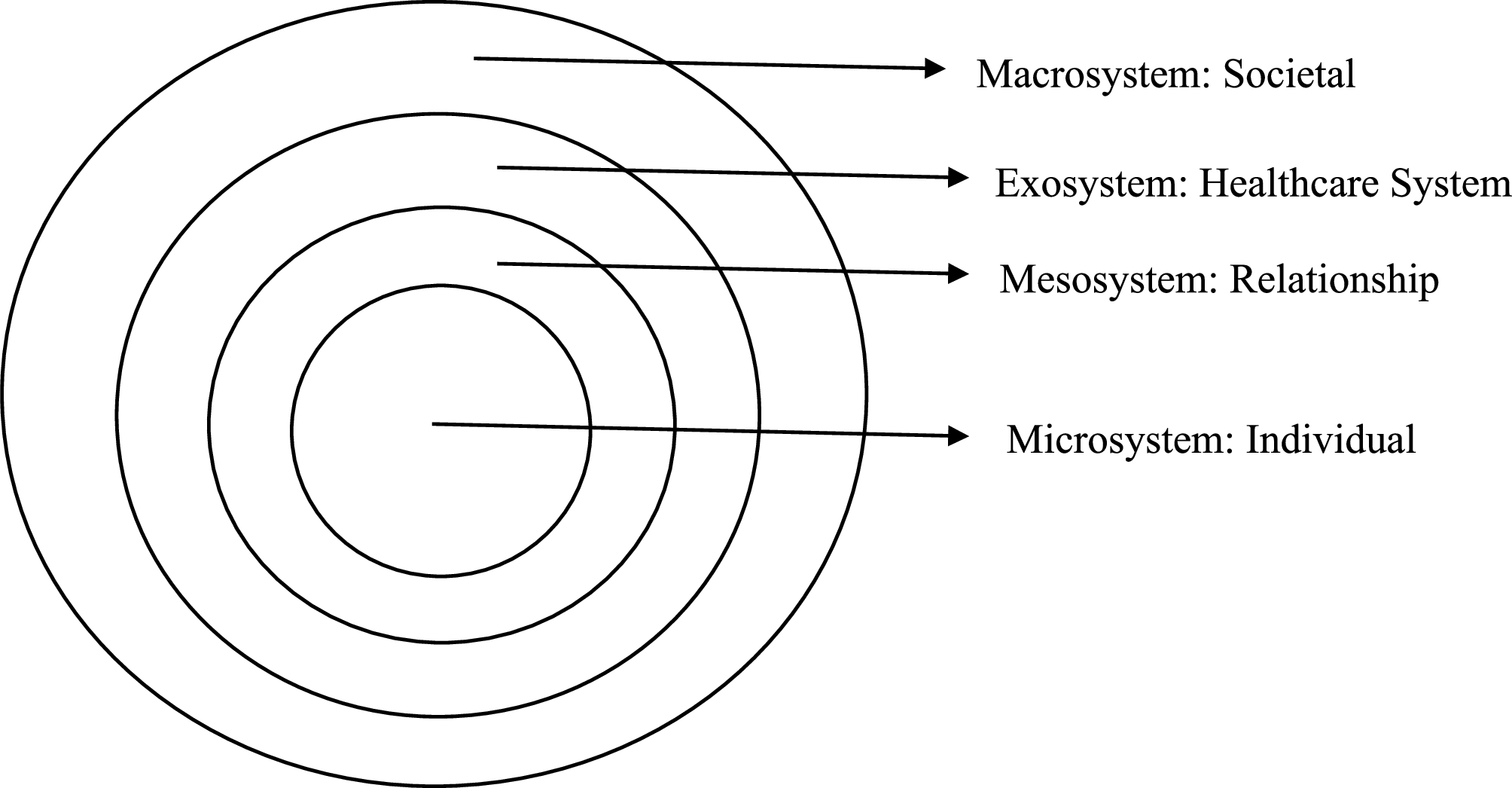

Thematic summary of experiences after EmCS drawing on the socio- ecological model

Our study revealed both positive and negative experiences with most women highlighting negative and a few reporting positive experiences (Table 2).

Positive experiences at individual level

Outcome of surgery was an important contributor to positive experiences following EmCS and all women had a successful EmCS. Safety and well-being of the baby was an important factor women considered in deciding for caesarean birth and hence feelings of positive experiences.

“By that time [prior to the caesarean section], I was just thinking about the baby since I was told it was all about saving the baby’s life.” (P-02).

One participant was altruistic in that she was ready to sacrifice her own life in favour of her baby’s life.

“Me as a person, I lost hope already and what I was looking up to was to save my baby. I didn’t mind whether I had life or not, but at least my baby to be saved.” (P-18).

Saving the woman’s life

Participants expressed happiness when they ultimately went successfully through surgery.

“I remembered my sister who was operated from here and she died, what if I didn’t survive like my sister, what would happen, I asked myself, but I prayed to God and He saved me.” (P-09).

As would be expected, the health care providers (KIs) reported that positive outcomes of labour with both baby and mother alive indeed contributed to great positive experiences.

“…what I have observed is that most women come in when they are in dire situation, now if they pull out alive, for them that is a good experience, if their baby pulls out alive, that is a good experience…” (KII-06).

Positive experiences at relationship level: presence of a family carer

Most participants reported receiving some form of care from their family members and friends, after CS, which was a great family contribution.

“At that point after the operation, you need someone on your side because you might not be able to handle your baby properly so for that purpose, my sister was there to handle my baby. From operation, if I wanted to change this and that, she was always there for that. If there was anything needed at home, my husband played that role… If anything was needed, I was given that hand.” (P-01).

One KI reported that support from the family following EmCS is important, as it is associated with positive outcomes.

“They need support from the family… they cannot walk, they may need to be fed, they need to be supported from bed, they need to be helped in terms of bathing and cleaning, they need to be turned in the bed for those who are very sick…and really you find that those who have companions, improve faster than those who are kind of neglected.” (KII-02).

Positive experiences in the health care setting

Our study found being managed in the national referral hospital was associated with positive experiences, as women trusted and had confidence in the system that is associated with quality care like counselling and guidance.

“They certainly gave me time to see if I could work out and push my baby, but it didn’t happen that was why I was taken for operation at last…and apart from the long waiting hours, the doctors and midwives really cared for me, I may not know them by names, but I really appreciated their work.” (P-01).

One key informant also confirmed this trust and confidence of being cared for in the national referral hospital.

“When a mother comes to KNRH, by all means they have to see a doctor…it is one of the reasons why Kawempe has high volume of patients…they say any time you go there, you will see a doctor and it is a doctor who will operate you and they believe these doctors are from Mulago…so they believe in us, they trust us, especially with good outcomes, despite difficulties at times.” (KII-02).

A section of the participants reported that the health care team counselled them on different aspects regarding EmCS. The experiences of other midwives helped them develop positive experiences.

“The midwives counselled me and one of them told me that all her four children were delivered through a C [caesarean section] and that I was equally going to be fine. I felt encouraged.” (P-13).

Negative experiences

Fear of uncertainty

Our study found fear of uncertainty related to fear to lose life, fear of losing motherhood (inability to conceive again), fear from her past own experience of surgery and experience of surgery by other family members and friends.

“It was my first time to have an operation, so I developed a lot of fear, and I thought I won’t come back from the theatre, definitely I would die from there, but when I reached there, I was given medicine, and I didn’t feel any pain after the caesarean section.” (P-14).

“I didn’t want caesarean method because I know what it means…I had a lot of pain in the previous surgery and so I knew what to expect following surgery, that was why I had to accept induction method so that I could push. I would have moved directly to the theatre, but I had to bear the induction[catheter] method, though it was not easy also, since they hadn’t told me the reasons why.” (P-01).

“I have a concern, now that I was operated, will I be able to conceive again?” (P-04).

One KI confirmed that inadequate pre-operative preparation of patients contributes to increased fear and anxiety during EmCS and that WHO now recommends use of anxiolytics before anaesthesia.

“…. a recent study recommends that a woman going for caesarean birth should be provided with a low dose anxiolytic drug to allay the fears and anxiety associated with EmCS.” (KII-06).

Negative feelings about decision of caesarean section

Generally, most women had negative feelings towards caesarean birth, as the expectation was for vaginal birth.

“To be sincere, I felt bad, and I even cried. At first, the midwives reassured me that I would be able to push, but later they told me I was going to be operated on. I really felt bad because I heard that most of those who go to theatre either the mother or the baby dies.” (P-17).

“I even tried getting some herbal medicines to help me have normal delivery, but still I ended up being operated on.” (P-20).

Based on experience and other studies, one KI reported that women generally prefer vaginal birth to caesarean section.

“Of course, most women would prefer to deliver vaginally and hope to deliver vaginally, but if the circumstances dictate that a caesarean must be done; some of them feel shattered. With proper counselling and informed consent though, some eventually take it positively. Those not counselled enough usually register more complaints post-operatively and become unhappy about the whole process.” (KI-05).

Most women associated EmCS with too much guilt, anxiety and distress.

“I had negative thoughts since I would see even the health workers also getting too worried. So, I also became distressed and scared… “of course everything was new, and I knew I wouldn’t come back alive…I ended up losing my uterus, and the pain was too much, the pain was really endless.” (P-16).

Lack of a companion

This was noted to have had a negative influence on the women following EmCS with no spouse, relative or friend around.

“I went through a lot, there were moments I needed food or drinks, but I couldn’t afford. Those that would attend to me, one would come spend like a minute and go back, yet I was too weak to stand on my own, I was in pain and the baby was in nursery and needed to be fed.” (P-10).

Some women felt it awkward, why their relatives were denied being with them during such a critical moment in their lives.

“My family members including my husband were there, but they were chased [sent] away from the hospital!” (P-16).

Through triangulation, KIs agreed that indeed these women went through a lot of distress without being supported by their family members after EmCS.

“Some of our women here…. I think are from poor families/poor background. They do not have attendants and lack basic needs…. making their lives miserable…one told me, ‘Thank you, thank you doctor for helping me, my husband had neglected me.’ (KII-02).

“Yes, they complain and that sometimes their attendants go back and leave them alone, that means they are at times abandoned.” (KII-03).

Unsatisfactory care from health care providers (HCPs)

At health care level, our study found key areas of unsatisfactory care ranging from delays in intervention, informal hospital charges, discrimination/neglect, poor communication and complications following EmCS.

Delays in receiving care

Women highlighted delays in accessing care and attributed this to presence of many patients on the queue and few health workers in the hospital attending to them.

“May be the obstetricians and Gynaecologists in Kawempe are not many, because if a woman is for emergency caesarean, she should be operated immediately. A woman can be in the queue for a long period before going to theatre…I was supposed to be operated from level four, but the place was full. I was transferred to level 3 but still there were 2 other women ahead of me, so I had to wait until those 2 were operated on.” (P-01).

Explaining about the delays, the KIs confirmed that patients may feel neglected as the waiting time is longer as compared to the recommended decision to incision interval of not more than 30 min for certain obstetric conditions.

“Kawempe is a high-volume centre, and patients go through a lot…you make a decision to operate except because of the numbers, there is a reasonable delay, and they then feel neglected.” (KII-2).

Poor communication

Explaining how they interfaced with some health workers, participants highlighted that some were harsh and rude to them. They further suggested that the health workers paid less attention to them and ignored to attend them at their hour of greatest need.

“The way they were talking to us at that time I was very sick and in bad shape, it was not good at all… They were harsh and rude yet that is not how it is supposed to be…. imagine someone telling you that he does not care and that I would either take or leave it. ‘It is a matter of life and death here…’ I heard this directly from the doctor who was going to operate on me. (P-15)

One KI also cautioned that patients need to be given optimal care but that it is not what usually happens on the ground. The number of women coming for care to KNRH is too big to being handled efficiently and effectively and this may be the reason why some staff go out of their professional way.

“Yeah, we try to give them the care, although we are overwhelmed with work, the way you care for 5 women is not the way one would care for 18 or more operated women per night; let’s say maybe you are alone, but we always try to do our best.” (KII–03).

Informal hospital charges

Our study found a unique finding of some staff extorting money from women for EmCS before accessing care, given that this is a public hospital with care meant to be free of charge.

“I knew that all services here were for free, but they asked for money after the surgery…especially the midwives that work in the theatre…Sometimes they would tell us that we first give them something so that they can work on us…They asked my husband, and he had to pay some money.” (P-15).

As the hospital would occasionally lack supplies and drugs, women felt neglected, especially where they were expected to fill the gaps themselves.

“If they [midwives] find you without medicine, they would not bother to get you medicine. They would just leave you there without treatment. You would see other women in pain because they had no medicine.” (P-19).

“One thing upset me even before the surgery. I was in pain, and I was told that I would be operated, so they took me for a check-up. There were two health workers; one female and the other male, so this female nurse told the male nurse to take me to theatre, but he looked unbothered and when he took me, he just stopped me on the way and the cleaners helped to roll me up to the theatre.” (P-10).

Complications following EmCS

A few women developed complications after primary surgery. They held negative views about EmCS, as they had to undergo repeat surgery.

“In the first operation, I didn’t know what happened. I reached home and got pain in stomach [abdomen] and I came back and was sent for a scan, which revealed nothing. They wrote for me some tablets and I was allowed home. Three days later, I saw pus coming out of me and on returning to the hospital, I was operated on again.” (P- 19).

Key informants highlighted that women occasionally get complications after CS and pointed out that some complications include puerperal sepsis, bladder injury and repeat surgeries.

“Of course, some have come up with complications like puerperal sepsis- the wounds getting infected, and they must undergo repeat operation. Some come out with experiences of urinary bladder injuries and must be referred for further care by an urogynecologist. However, most women after caesarean section heal rapidly well and are discharged uneventfully.” (KII-05).

Thematic summary of support needs of women following EmCS in KNRH

In the analysis of the support needs of women following EmCS, four areas of support needs were identified: financial needs, family and friend’s needs, treatment and information needs (Table 3). These needs were expressed at individual, relationship and health care level.

Financial needs

Most women expressed needs for financial resources and lack of which affected them from accessing care from the hospital in a timely manner.

“I needed money because they asked from me 30,000 Uganda shillings for scan. I never had it and that was why I delayed accessing the theatre. I spent 2 days here before going to the theatre, because they told me that they couldn’t take me for the operation before the scan.” (P-03).

Most women had to find ways of buying supplies themselves, as the hospital would occasionally run short of supplies and drugs.

“I needed money for buying drugs. They tell you to go buy them yourself from the pharmacies for your own use.” (P-05).

Needs from family and friends

The need for family members to be around following EmCS was important to support them with daily routine activities like helping with ambulation, feeding and washing. The need for the family’s presence helped women in navigating through their post-operative period with ease.

“From the time of operation, if I wanted to change position or visit the washrooms, my sister was always there for that. If there was anything needed at home my husband played that role.” (P-02).

“If there was something needed, they (my family) would be the ones to go look for it, or if there was any medication needed, they would be there to support me with it.” (P-01).

Need for pain control

Following EmCS, most women expressed the need for pain control. Uncontrolled pain contributed much to their negative experiences of EmCS.

“I needed my pain controlled, because I was in too much pain, the pain was endless. The pain was unbearable.” (P-16).

“What I will never forget is the insertion of urine pipe [urinary catheter] and that was my worst experience.” (P-12).

“I had pain in the private part [perineum] and my walking style changed… I couldn’t walk normally…The pain was too much but with time it went on reducing although the catheter brought continuous pain, especially while walking.” (P-14).

On the issue of pain, the KIs agreed with the women and reported that women endure much pain after surgery, mainly resulting from missing treatment when they have no money to buy drugs themselves.

“Sometimes, you find them struggling to get treatment; some of them are in great pain and complained that they never received treatment on time.” (KII-02).

The KI further stressed that pain control after EmCS is an integral component of quality care.

“…because of the pain following EmCS, WHO recommends all women for EmCS are to be on intrathecal morphine and patient-controlled analgesia for them to determine their own level of pain, as the midwives may be overwhelmed. We now advocate for all these approaches in KNRH, and we have started seeing improvement in the quality of care we offer these days.” (KII-06).

Information needs -Counselling and guidance

Women expressed needs for information about EmCS in general and that lack of which increased their fears and anxiety about the whole process.

“I wanted to know how my baby was doing inside since they had said the day I was to deliver had passed. I wanted to know if the baby had a problem inside, but I did not get the answer. they did not tell me and when I asked the medical personnel, she kept quiet. I also wanted to know the sex of the baby, but they said the baby had already grown up and it was hard to know the sex.” (P-17).

In agreement with the participants, the KIs stressed that women need adequate preparation to make the experience of labour enjoyable. Part of this preparation includes providing adequate information to them.

“…these women needed support in form of information so that they feel cared for really… they need more information while consenting them and giving them alternatives as well. They need nutritional advice and simple exercises like stretching. We usually don’t want to waste time because the number is already big, and we try to reduce on the waiting time.” (KII-06).

A striking finding was that one woman expressed lack of information regarding the indication for EmCS and considered that she never felt it right for her to be operated on.

“They just told me that I was going for caesarean section. The pregnancy was due and at first, they said I would push…. they gave me medicine of inducing labour pains and they measured me, and I had reached 3 cm. Afterwards, they just came and told me to go to theatre without further information.” (P-11).

The KIs confirmed that they do not offer adequate care to the extent that some patients do not know the reason why they are operated. In addition, a few go home with unresolved questions surrounding the operation they underwent.

“Most of them [women] didn’t know why they were operated on; they could not explain the reasons for the operation…like they could not explain that they were operated on because of ABCD…” (KII-02).