Researchers in Israel have shown that individuals possess distinctive patterns of breathing – fingerprints – which can be used to identify them with near-perfect accuracy. The team’s findings also indicate that these nasal breathing patterns may offer insights into both physical and mental health.

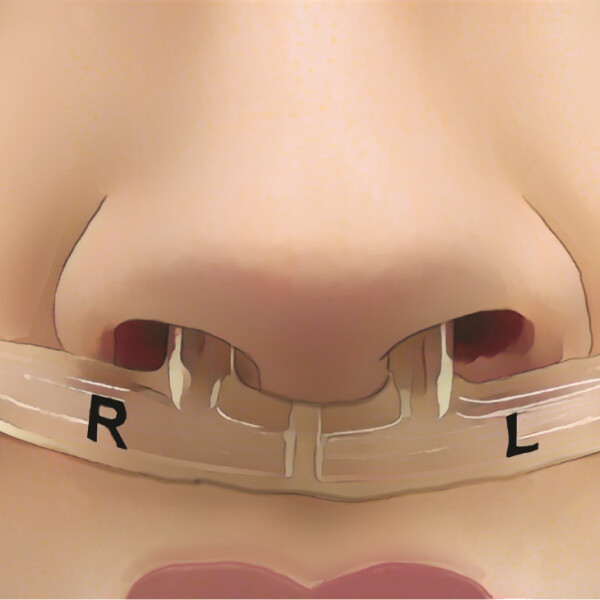

The study was conducted by a team at the Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel. They developed a lightweight wearable device that recorded nasal airflow over a 24-hour period, using soft tubes positioned beneath the nostrils. While breathing is typically measured in short bursts to assess lung function, the researchers sought to capture a more complete physiological profile by recording over an extended duration.

Professor Noam Sobel, the study’s senior author, explained that the research was originally driven by curiosity about olfaction and its close connection with the brain.

“You would think that breathing has been measured and analysed in every way,” he said.

“Yet we stumbled upon a completely new way to look at respiration – we consider this a brain readout,” he added.

The team equipped 100 healthy young adults with the device and allowed them to go about their daily routines. Analysing the airflow data, the researchers were able to identify individuals with 96.8 per cent accuracy. This level of precision was maintained across repeated tests conducted over a two-year period and was comparable to that of advanced voice recognition technologies.

“I thought it would be really hard to identify someone because everyone is doing different things, like running, studying or resting. But it turns out their breathing patterns were remarkably distinct,” said Timna Soroka, co-author of the paper.

Beyond identification, the study found correlations between these respiratory signatures and a person’s body mass index, circadian rhythm, emotional state, and behavioural characteristics.

For example, participants who reported higher levels of anxiety tended to have shorter inhalations and more irregular breathing pauses during sleep. Although none of the participants had clinical diagnoses, the findings suggested that long-term monitoring of nasal airflow might serve as a sensitive indicator of health and mood.

“We intuitively assume that how depressed or anxious you are changes the way you breathe. But it might be the other way around,” Sobel added.

“Perhaps the way you breathe makes you anxious or depressed. If that’s true, we might be able to change the way you breathe to change those conditions.”

The researchers acknowledged limitations in their current device, which only measures nasal – not oral – breathing, and may shift during sleep. Moreover, the visible tubing might deter potential users due to its resemblance to medical oxygen equipment. A more discreet and practical version is in development.

Looking ahead, the team hopes to explore therapeutic applications.

“We definitely want to go beyond diagnostics to treatment, and we are cautiously optimistic,” said Sobel.

For further reading please visit: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.05.008