Small cell carcinoma of the ovary used to be classified as a tumor of the ovary and subclassified into SCCOHT and SCCOPT in the prior WHO classification [1], but is now subclassified into SCCOHT and OSCNEC [2]. OSCNEC is classified in the new chapter of neuroendocrine neoplasia, which consolidates neuroendocrine neoplasia in gynecological sites such as ovary, uterine corpus and cervix, whereas SCCOHT remains classified as a tumor of the ovary. Therefore, SCCOPT is thought to correspond to OSCNEC pathologically despite this change in pathological classification. OSCNEC are pathologically similar in morphology to neuroendocrine carcinomas of the lung, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, uterine cervix, and uterine body. OSCNEC and SCCOHT are clinically and histopathologically distinct entities. SCCOHT, which is more common and occurs in adolescents and young women with hypercalcemia, is strongly associated with somatic mutations of SMARCA4 [15]. In contrast, SCCOPT of the ovary, which is not related to this gene mutation, is rarer, occurs more often in peri- or postmenopausal women, and is not associated with hypercalcemia.

SCNEC can occur in the gynecological tract and accounts for less than 1% of gynecological malignancies [2]. SCNEC other than cervical SCNEC typically presents after menopause, consistent with this case. Due to the rarity of OSCNEC, few reports have described possibly characteristic clinical data like preoperative serum NSE levels and detailed MR imaging findings. Most notably, FDG-PET findings associated with preoperative diagnosis have never been reported.

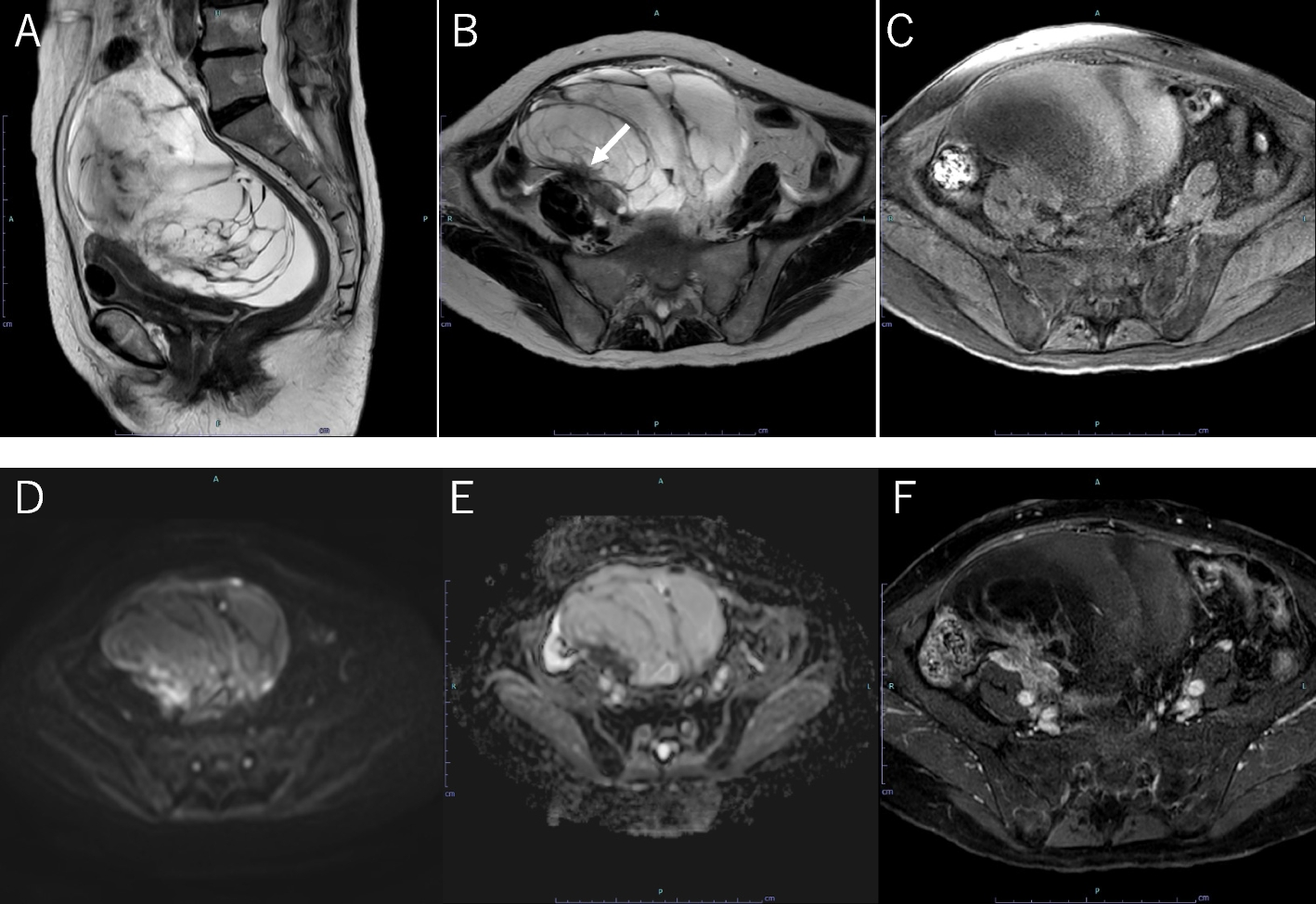

On MRI, this case of OSCNEC appeared as a multicystic mass including hemorrhage and solid component. Septa inside the tumor were irregular, and the solid component showed high SI on DWI and contrast enhancement. In reports describing imaging findings of OSCNEC and SCCOPT on CT and MRI (as shown in Table 1), the morphology of OSCNEC is described as a lobulated mass consisting of not only solid but also cystic components, as in this case. Cystic components sometimes contain hemorrhage, necrosis and/or rupture [4] [7]. These findings are also observed in primary ovarian neoplasms other than OSCNEC and are not specific. Thus, it may be difficult to differentiate OSCNEC from malignant ovarian epithelial tumors such as metastatic ovarian tumors and mucinous carcinoma.

In the present case, high FDG uptake (SUVmax: 13.0) was detected in the solid component, para-aortic lymph node, spinal, iliac, and liver metastases, and peritoneal dissemination on 18F-FDG PET/CT. To our knowledge, this is the first case report to describe 18F-FDG PET/CT findings. In previous reports, average SUV max was 7.8 in 66 primary malignant ovarian neoplasms except for OSCNEC [16], compared with 11.3 (range: 2.5–57.6) in primary small cell lung cancer (SCLC) of all stages [17]. Despite this significant overlap in range, SUV max was significantly higher in SCLC. Consequently, OSCNEC may be similar to SCLC not only in pathological morphology but also in high FDG uptake.

Generally, lymphatic metastasis and peritoneal dissemination are the most common metastatic routes in ovarian epithelial cancer, while hematogenic spread is rare [18] [19]. In contrast, NECs of the ovary show significantly higher tendencies for bone, brain, and liver organotrophic metastasis than epithelial ovarian cancer such as endometrioid carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, serous carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma [20]. In the present case, hematogenic spread as bone and liver metastases were detected by 18F-FDG PET/CT. Bone metastasis was a particularly notable finding in reports of OSCNEC of the ovary or SCCOPT that mentioned the metastatic sites: three of the six cases with distant metastases had bone metastases, as shown in Table 2. Detection of bone metastases affects the pretreatment staging directly, but is sometimes difficult on CT, especially when bone metastases are intertrabecular vertebral metastases (IVM). SCLC, hepatocellular carcinoma and hematologic malignancies, which have a poor tumor stroma, tend to form IVM. As IVM do not alter the trabecular bone structure [21], they often go undetected on regular imaging modalities that detect osteolytic or osteoplastic structural deformation, such as CT and bone scintigraphy [21]. However, 18F-FDG PET/CT could detect bone metastases which were not identified by CT [22], corresponding to the clinical determination of IVM in this case (Fig. 2). Ovarian cancer staging is ultimately determined through surgical findings. However, distant metastases, including hepatic, pulmonary, and osseous involvement, cannot be accurately assessed intraoperatively and rely solely on imaging evaluation. Therefore, PET/CT may contribute to precise preoperative staging, ensuring a more comprehensive assessment of disease burden and treatment planning.

In this case, serum levels of NSE were elevated preoperatively. Suzuki [4] reported elevated preoperative serum levels of NSE at 177 ng/ml, and NSE elevation was always accompanied by evidence of recurrence on imaging after surgery for SCCOPT. Yin et al. [7] also reported elevated serum NSE even 10 days after palliative surgery for right ovarian SCCOPT with uterine endometrial cancer metastasizing to the left ovary. NSE, known as enolase-γ, is a neuro- and neuroendocrine-specific isoenzyme of enolase, which is a key enzyme in aerobic glycolysis [23]. Elevated NSE can be observed in several neuroendocrine or neuronal tumors such as SCLC and neuroblastoma [24] [25]. Serum levels of NSE are frequently elevated in SCLC at the time of diagnosis, decrease after remission, and rebound after recurrence [26] [27] [28]. Because OSCNEC is similarly a high-grade carcinoma composed of small to medium-sized cells with scant neuroendocrine differentiation, elevated serum NSE level may also imply OSCNEC in the diagnosis of ovarian tumors, although it is difficult to distinguish OSCNEC from metastatic small cell carcinoma of the lung. Therefore, FDG-PET, which can detect even IVM and rule out primary SCLC in patients with primary ovarian tumors, may be helpful to suggest primary ovarian OSCNEC as a differential diagnosis. Furthermore, since NSE is not routinely measured preoperatively, the identification of hematogenous dissemination, particularly manifesting as bone and liver metastases—as observed in this case—may serve as a clinical prompt to assess NSE levels. This could not only facilitate the early suspicion of OSCNEC but also enhance the detection of postoperative recurrence, thereby contributing to more effective disease monitoring and management.

Preoperative diagnosis of OSCNEC by CT or MRI alone is considered difficult due to the lack of specific findings. However, OSCNEC could be considered when elevated serum NSE at diagnosis and hematogenic spread such as bone or liver metastases are found in a patient with a primary malignant ovarian tumor who does not have a lung tumor on imaging.