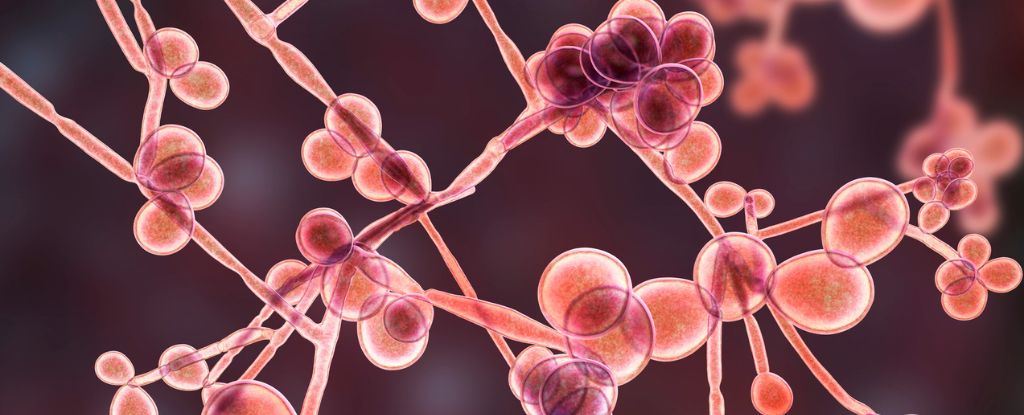

The fungus behind yeast infections is a mercurial beast, and there’s something specific in human blood that may flip its switch from friend to foe.

Researchers in Europe have now found that albumin – the most abundant protein in human blood plasma – is a corrupting influence that brings out the worst in Candida albicans.

The findings help explain why this highly prevalent yeast is so difficult to study outside of the human body.

Today, C. albicans colonizes most of the human population, and it is typically harmless, living peacefully in and on our mouths, guts, and genitals. At the slightest moment, however, the opportunistic pathogen can turn on us, like when our immune systems weaken, or when we finish a course of antibiotics and there’s new room to grow.

Related: Dangerous Fungal Infection Sees a Dramatic Increase in US Hospitals

At that point, C. albicans is not so agreeable; in fact, it can be downright irritating and painful, causing uncomfortable conditions such as thrush. In extreme cases, the infection can even enter the bloodstream and invade our organs.

It’s a duplicitous character with potentially fatal outcomes, and to the great frustration of researchers, the pathogen keeps playing nice when under scrutiny.

Even when samples are taken directly from yeast infections, C. albicans may suddenly act as if it isn’t virulent when isolated in the lab. The same is sometimes true when the pathogen is transferred to the bloodstream of rodent models.

“That didn’t add up,” recalls microbiologist Sophia Hitzler from Germany’s Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology – Hans Knöll Institute.

“We suspected that some important host-specific signal was missing from our test systems – and albumin was a likely candidate.”

In 2021, Hitzler was part of another team that found albumin enhanced the toxicity of C. albicans on vaginal skin cells. Together with microbiologist Candela Fernández-Fernández, Hitzler has now led a fresh round of experiments to investigate further.

Using human cell models, most of which came from the vulva, the team has revealed that albumin is a ‘bad’ influence on C. albicans, even when researchers raised ‘good’ yeast with all their virulence genes deleted.

In fact, human albumin had such a profound impact on yeast, it rewired the pathogen’s metabolism.

This led to C. albicans becoming increasingly toxic to human skin cells. The infection also grew extra fast, forming dense biofilms, which is a classic pathogen move.

Even when researchers deleted the most detrimental genes from their yeast samples, human albumin somehow restored the pathogen’s toxicity, allowing it to wreak havoc on human skin cells once again.

“The fungus doesn’t necessarily need to grow long hyphae or produce great amounts of toxin in order to cause infection,” explains Fernández-Fernández.

“Depending on the condition it’s facing, it will adapt—and it can take advantage of the host.”

The findings suggest that future research on fungal infections need to consider the complexities of the host’s physiology, too. Human albumin may not be the only factor that influences how C. albicans behaves.

“Just providing essential nutrients in the lab is not enough,” says Hitzler. “You need the right environmental cues. Otherwise, you might overlook strains that are actually dangerous in the human body.”

The World Health Organization considers C. albicans one of the most dangerous fungal infections in the world. And while fungal infections, like bacteria, can develop resistance to medications, they receive far less scientific attention by comparison.

If researchers wish to fill that gap, figuring out how to properly assess a fungus’ toxicity in the lab will be crucial.

The study was published in Nature Communications.