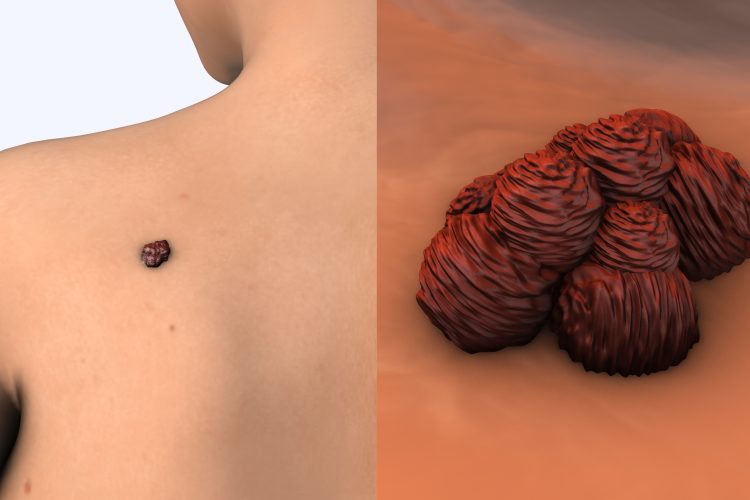

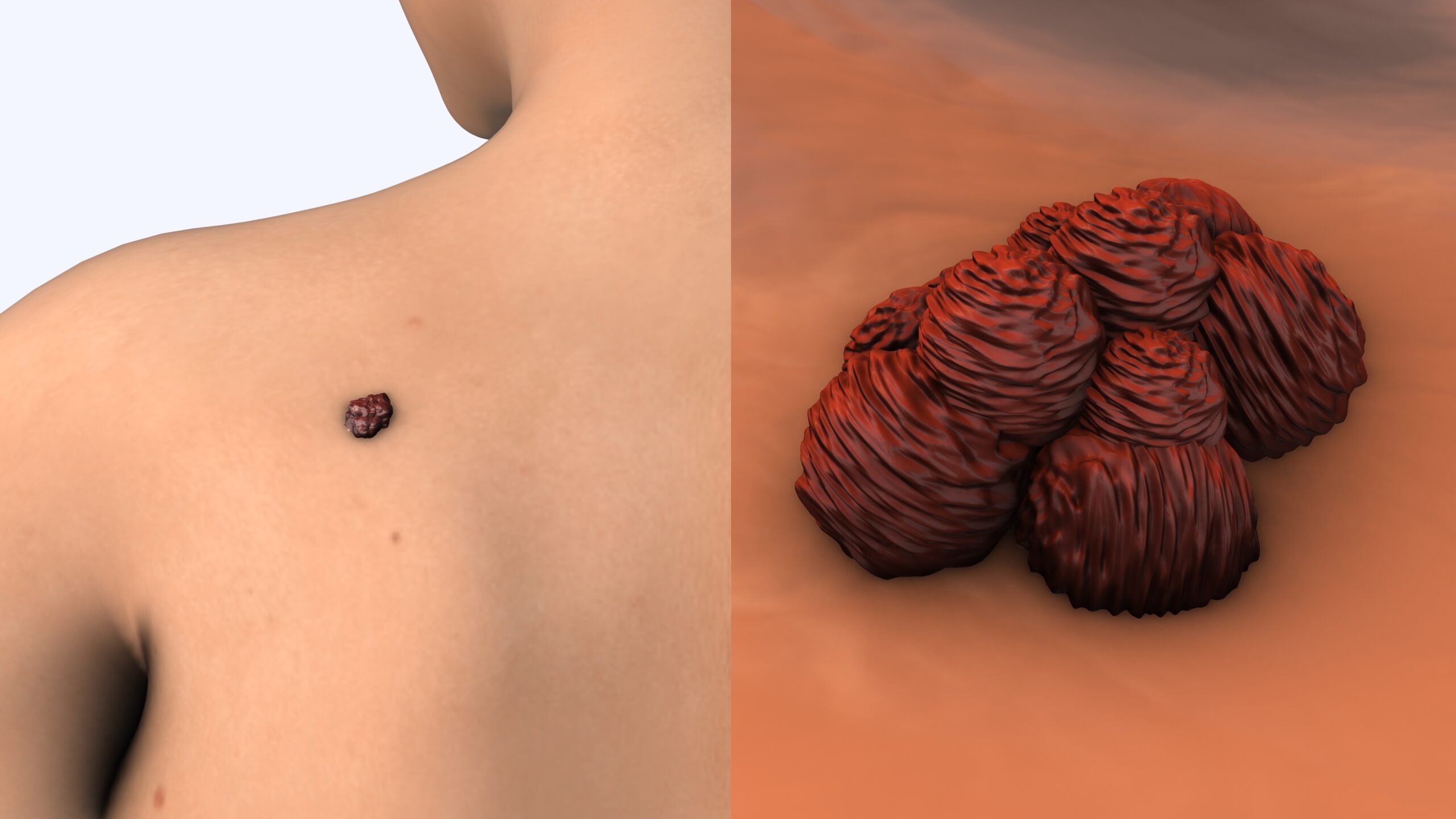

New research has discovered a key survival mechanism in metastatic melanoma, revealing that cancer cells spreading to lymph nodes depend on a protein called FSP1 to avoid cell death.

Scientists at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of…

New research has discovered a key survival mechanism in metastatic melanoma, revealing that cancer cells spreading to lymph nodes depend on a protein called FSP1 to avoid cell death.

Scientists at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of…