If we get it right, the world could save more than 1.2 million lives every year.

In the United Kingdom, tuberculosis (TB) is a disease you only hear about in history class. It is taught alongside lessons on the large cholera epidemics in the 19th century, the Black Death, or the Spanish flu pandemic. Across the rich world, TB was once a huge killer, but it is a disease that is largely consigned to the past. Death rates are very low in high-income countries.

However, TB is still very common in large parts of the world. It kills 1.2 million people every year, more than any other infectious disease.1

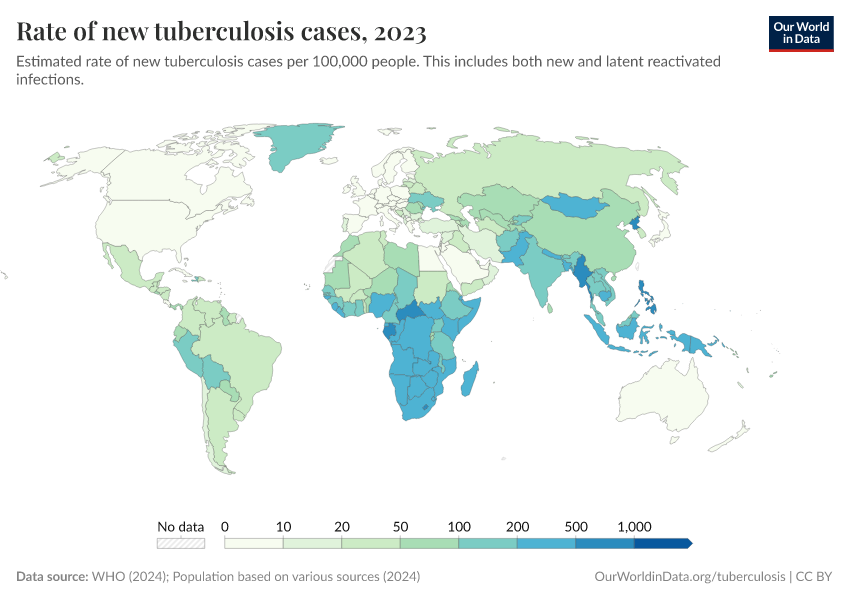

Someone in Lesotho, the Central African Republic, or Gabon is at least 3,000 times more likely to die from TB than someone in the United States or Denmark. You can see these huge differences in death rates in the chart below.

This inequality is unacceptable. We know what causes tuberculosis and how it spreads. We’ve known how to test and screen for TB for over a century. And we’ve had effective antibiotics to treat it for over 70 years. We could make fast progress against this disease at a relatively low cost. And there’s a lot at stake: as we explained in one of our previous articles, closing the gap between countries like the United States and elsewhere would save over one million lives a year.

In this article, we look at why there are such large differences in TB death rates, and what can be done to resign tuberculosis to the history books, everywhere.

Let’s start with the question of why someone in Lesotho is thousands of times more likely to die from tuberculosis than an American of the same age.

There are two elements to this: the risk of getting an active tuberculosis infection, and then the risk of dying from it. The average person from Lesotho is at a much higher risk of both.

The left map below shows the huge differences in the rates of new TB cases. Someone in central Africa is hundreds of times more likely to be infected than in North America or Europe.

But after infection, someone with an active TB infection in a poorer country also has lower odds of surviving. Getting tested and diagnosed is typically slower (when people are diagnosed at all) because of weaker healthcare systems. That means the disease is treated late. And while TB can be cured with antibiotics, many people can’t afford the full course of treatment or struggle to complete it, since it can last more than a year.

On the right map, you can see the share of people who are diagnosed with TB and die from it (the case-fatality rate). In most rich countries, less than 10% do. In poorer countries, this can be more than three times higher.

TB is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacterium that spreads from person to person through water droplets. Having access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene products greatly reduces people’s exposure. That is one reason why rates tend to be higher in lower-income countries.

Many people have “latent tuberculosis”, which means they have been infected with the bacterium but it’s inactive in their system: they don’t have any symptoms, and they can’t spread the disease.2 In this case, the bacteria are effectively surrounded by granulomas — small clusters of immune cells — that stop them from multiplying and keep them suppressed. But when someone’s immune system weakens or is compromised, the bacteria can break out of these granulomas and multiply. That person then has “active tuberculosis”, which means they are contagious and develop TB symptoms.

Various risk factors increase the chance of developing an active TB infection. Malnutrition is the biggest problem, and it’s much more common among lower-income individuals. Having HIV/AIDS is another issue, and HIV is much more prevalent across Sub-Saharan Africa.

In the rest of this article, we’ll focus on what can be done regarding detection, medical prevention, and treatment. But it should go without saying that improving living standards overall — tackling malnutrition, and improving access to water and hygiene — would also make a big difference in reducing rates of tuberculosis. It would have many positive spillovers for preventing other diseases, too. It was these general improvements in living conditions that led to the massive drop in tuberculosis deaths in Britain and the United States, even before effective treatments had arrived.

Let’s start with one of the earliest interventions that can protect a child from developing tuberculosis: a vaccine.

As early as 1921, decades before the development of antibiotic treatments, the scientists Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin had developed the “BCG vaccine”, which can protect infants and young children from severe tuberculosis.3

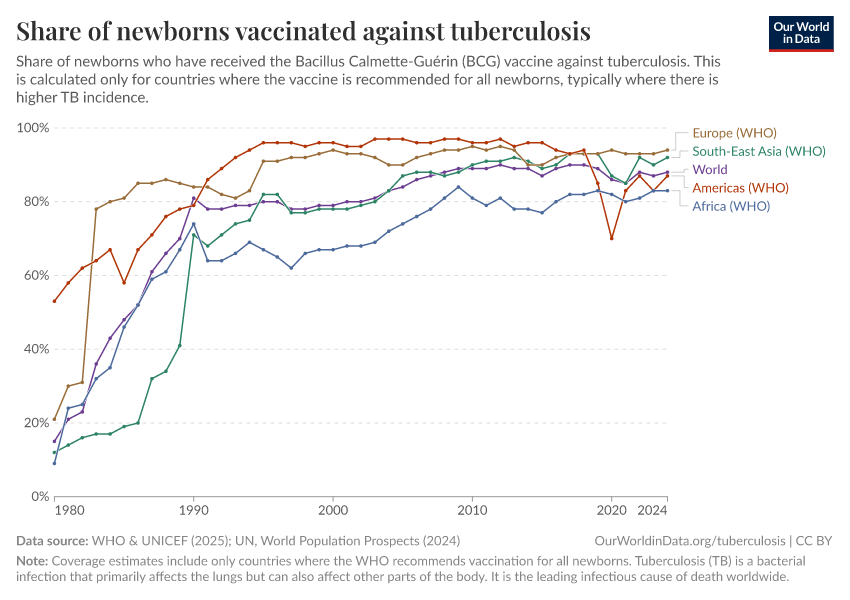

Over the next fifty years, its usage grew slowly and was mostly consigned to rich countries. However, by the 1980s, international efforts led by the World Health Organization focused on making the vaccine accessible everywhere. The chart below shows the rapid uptake of the BCG vaccine across regions, particularly in the 1980s and 1990s. It’s now one of the most widely used vaccines in the world.

But many infants are still left behind: the global share of newborns vaccinated against TB has stagnated at around 88% for fifteen years.

The BCG vaccine is not effective for adults. In children, it typically reduces the risk of severe tuberculosis by around 70% to 80%, but it tends to be less effective in countries close to the equator, which is a problem because this is where children are at the highest risk. This is likely due to several factors, such as the commonality of different strains of the TB bacterium in different parts of the world, interactions with other bacteria in the environment, and differences in immune response.4

Despite being less effective in some countries, the BCG vaccine still protects children and is a cheap way to do so. The average dose typically costs less than $0.20.5 Once we factor in distribution and delivery costs, the costs in low-income countries are around $2.6 That’s still extremely cheap for a potentially life-saving vaccine, and as we’ll see later, far more affordable than an extensive course of treatment if someone has tuberculosis.

Ensuring the vaccine is available to every child who would benefit is a first step towards beating the disease.

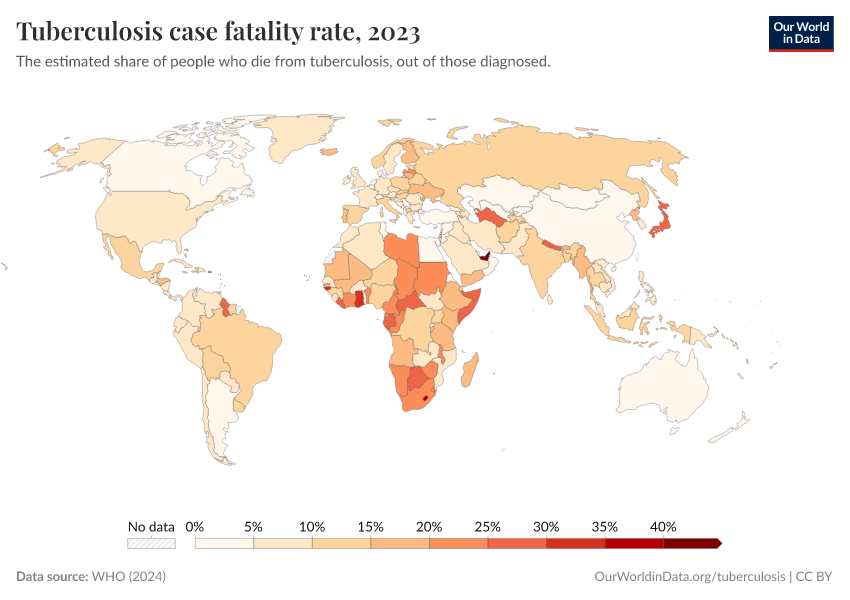

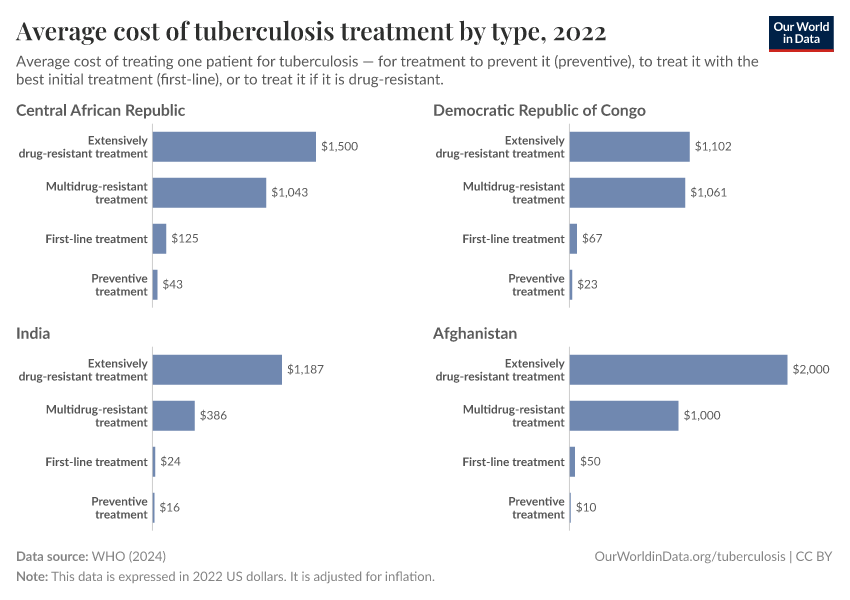

The chart below shows that preventing TB is much cheaper than treating it.

Preventive treatment is given to people with an inactive tuberculosis infection to stop it from becoming active, or to those at high risk of being infected. These measures typically have an effectiveness of 60% to 90% in preventing an active infection. These treatments are not given to everyone, and are targeted at those living with people who have tuberculosis, or have compromised immune systems, due to factors like HIV/AIDS.7 These preventive treatments involve a 3, 6, or 12-month course of antibiotics that must be taken daily (or for some drugs, weekly).

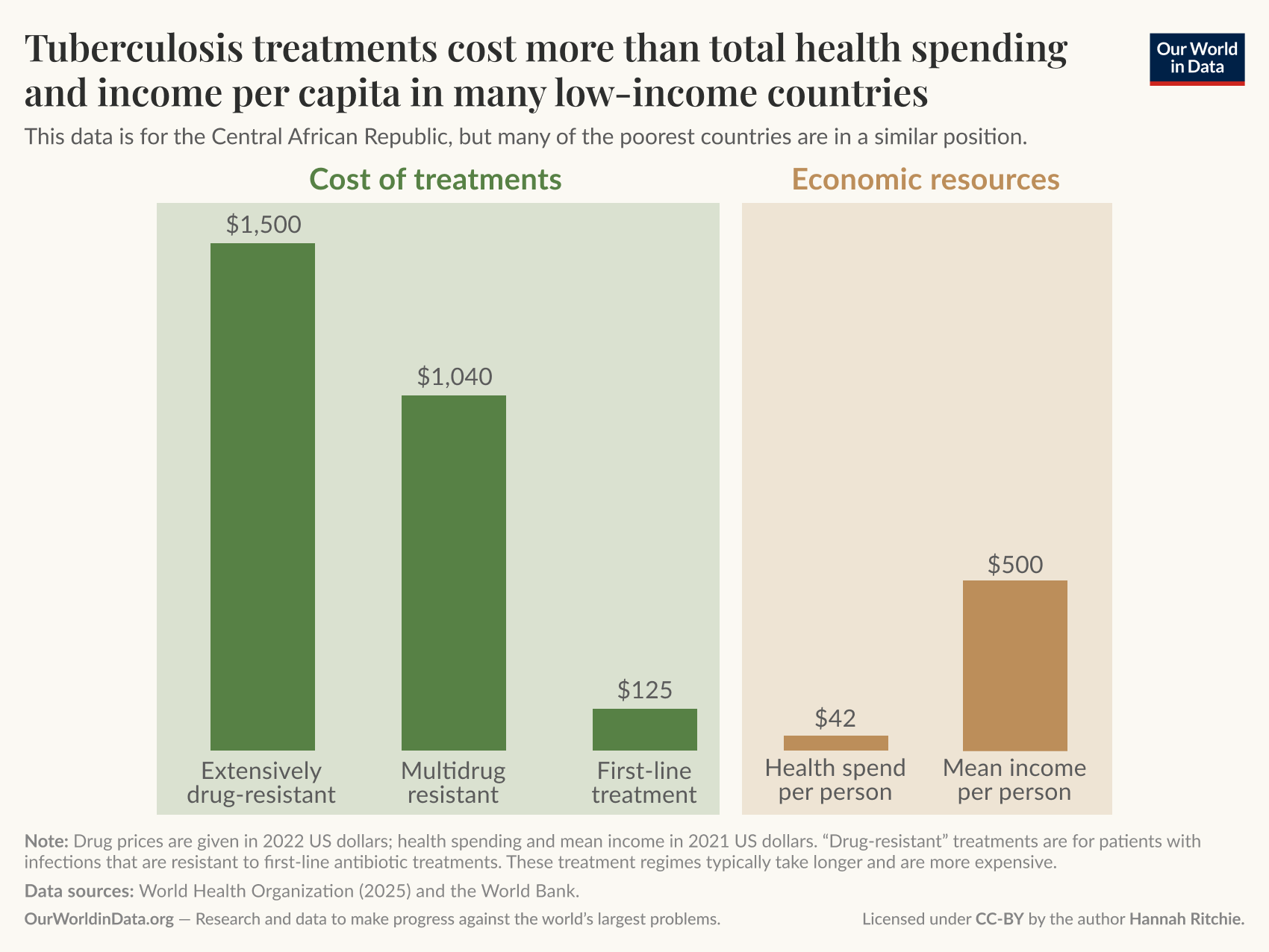

The symptoms, pain, and risk of severe TB are the main reasons to prevent someone from developing an active infection. But it also makes sense economically: treating active tuberculosis is more expensive, especially if it becomes drug-resistant. The chart shows that treating drug-resistant TB can cost many hundreds or over a thousand dollars.

To accurately target preventive interventions, people need to know whether they are at risk. A key part of that is screening and testing. If you’re living with people who have active tuberculosis, you can get treatments that dramatically reduce the risk of catching it. If you don’t know they have TB — or realize too late — then the opportunity to prevent it is gone.

Mass and community screening programs were vital tools that high-income countries — like the United States and many in Europe — used in their 20th-century battles against TB. These programs were often extremely effective in finding unknown cases so that patients could start their treatments, and others could be given preventive treatments early to stop the spread.

As one example, in 1957, the city of Glasgow in Scotland implemented the largest mass chest x-ray screening program to date, to identify hidden cases of TB.8 Before the program, TB infections had fallen at around 2.3% per year. After the intervention, the rate of decline more than doubled to over 5%.

We might not be able to roll out screening programs at this scale everywhere, but it shows how important testing is to reducing the spread of TB.

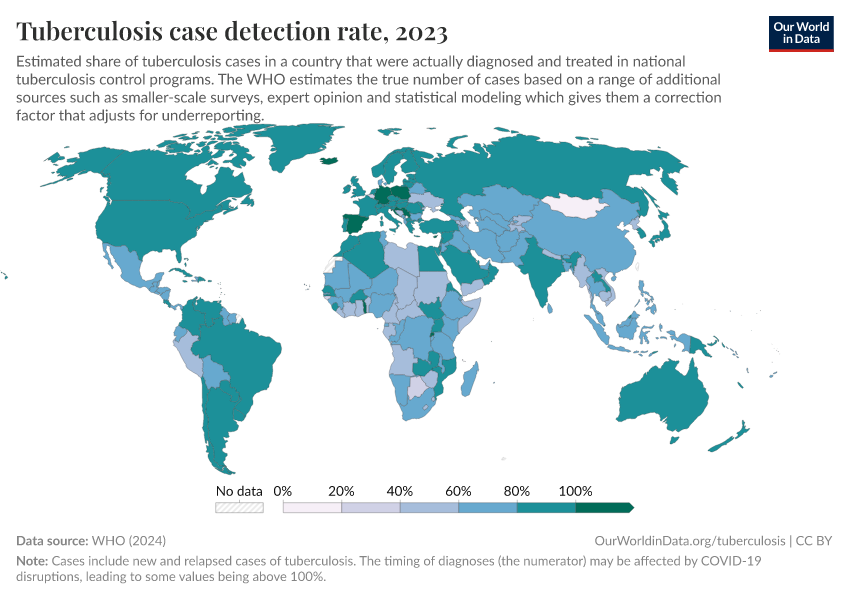

As you can see in the map below, the detection rate of cases — the estimated share of all cases that are diagnosed and treated — is below 60% in many low-income countries. This dramatically reduces their ability to stop the spread.

To be clear: the point here is not that we put all of our resources into cheap preventive treatments and forget about treating those who already have a TB infection. Both are crucial.

Most people who develop an active infection can be treated and cured with first-line drugs. Their strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis can be killed or controlled with standard antibiotic drugs that we’ve had for over 50 years.9

These treatment regimes can often take 6 to 12 months, but are effective. As we saw from the chart earlier, they cost between $30 and $150 per person. This is the reality for more than nine out of ten people with tuberculosis.

But standard drugs don’t work well for around 700,000 patients worldwide. Their strain has developed a resistance to the antibiotics that are effective for others. This can come in two forms. Those with “multidrug-resistant TB” do not respond to treatment from the two main first-line drugs: rifampicin and isoniazid. Those with “extensively-resistant TB” are also resistant to second-line drugs.

Treating drug-resistant TB takes longer and is much more expensive. Rather than costing tens to a hundred dollars, it usually costs over a thousand. This is still prohibitively expensive for many people or governments.

But as this next chart shows, even treatments against extensively drug-resistant TB have gotten much cheaper in the last five to ten years. In some countries, like India, Pakistan, or Zimbabwe, treating TB would have cost as much as $12,000 per person. Since then, costs have dropped to hundreds or a few thousand dollars.

This has happened for several reasons. First, alternative treatments have been developed; they replace injections with oral tablets, making them cheaper and cutting treatment time down to six months.

International health agencies, such as the WHO and the Stop TB Partnership, have also developed global procurement systems that have reduced costs for many countries.

Finally, some of the patents for these TB drugs expired, meaning other generic manufacturers can now produce them at a lower, more competitive cost.10

These changes in patents — and the cheaper drugs that resulted — have made these life-saving treatments much more accessible to some of the poorest people in the world. They will have saved lives. But the cost of battling and treating TB is still a huge barrier for many people in the world. Without further progress, many are at risk of being left behind.

Imagine you are a parent living in the Central African Republic, and your child has tuberculosis. The public health system is stretched, and inadequate funding for proper testing means they are diagnosed late and have developed a strain that is resistant to standard antibiotics. Without treatment, your child will die within six months.

Multi-drug-resistant treatment will cost around $1,000 (in US dollars). In the Central African Republic, the average amount spent on healthcare per person per year is just $42, and half of that comes from “out-of-pocket” sources — families paying for treatment themselves.11 As an average person, you live on around $435 a year, so all of your money would be needed to cover TB treatment for your child.12 This is a truly terrible position for a parent to be in.

Some parents might even face a worse situation: not only does one of their kids have tuberculosis, but they have the disease too. That doesn’t just add hundreds to thousands of dollars in treatment costs, but also means they can’t work for at least six months. The major source of income is gone.

We’ve picked some of the most extreme circumstances to illustrate this: the Central African Republic is one of the poorest countries in the world. But the reality is that millions of people across low- and middle-income countries face crippling costs of TB treatment every year.13 Researchers looked at national survey data across 22 countries and found the average total cost of an episode of TB to be around $1,250.14 While we often focus on the cost of the medicine and procedures, they cost “just” $200, on average. Around $500 came from the indirect costs of travel, food, and accommodation — remember, these courses of treatment can last well over a year. Finally, another $500 came from the indirect costs of lost income from being out of work.

Three-quarters of the poorest households experienced “catastrophic” costs, defined as spending more than 20% of the household’s income on TB. Even among the richest families, one-quarter had to spend more than that.

For the small share who have drug-resistant tuberculosis, the costs are even more prohibitive. The result is that most of a household’s income is spent on medical treatment. Or even worse: they do not have enough money, and have to watch their family members die as a result.

You might say that this pressure shouldn’t be on individuals. Governments should pay. However, the reality is that governments in many countries do not have the resources to cover these costs. In many countries, a large share of health spending is paid “out-of-pocket”. This is also true specifically for tuberculosis.15

That is why international funding is so crucial if we want to beat tuberculosis. External aid already plays an important role today. If we look at budgets across low-income countries that have high levels of TB, less than 20% of their funding comes from domestic sources.16 The remainder comes from the Global Fund (a program that provides funding to beat TB, HIV, and malaria) and other international donors. While money from richer donor countries makes up a large share of these budgets, the absolute sums are small. What is a tiny contribution from countries like the UK or the US is a life-saving intervention for someone in Ethiopia, Uganda, or Mozambique.

Despite this support, there are still large gaps in the budget. Those gaps represent people with TB potentially dying from the disease because they do not have enough money to pay for treatment.

Humans have been at war with tuberculosis for thousands of years.17 For most of that time, we didn’t know what it was, how it spread, and we had no way of treating it. It was one of our biggest killers for long periods.

While no country has eradicated TB, many have made the disease extremely rare. There is no reason that the rest of the world cannot follow the same path.

In our first article in this series, we looked at TB deaths in some of the poorest countries compared to historical rates in Britain. England and Wales used to be in a far worse position than some of the worst-hit countries today.

Driving these rates down quickly — especially with improved antibiotics and international support — is possible elsewhere.

Acknowledgments

We thank Max Roser, Saloni Dattani, Edouard Mathieu, and Simon van Teutem for valuable comments and feedback on this article.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie and Fiona Spooner (2025) - “The world left its fight against tuberculosis unfinished — how can we complete the job?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/ending-tuberculosis-save-millions' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-ending-tuberculosis-save-millions,

author = {Hannah Ritchie and Fiona Spooner},

title = {The world left its fight against tuberculosis unfinished — how can we complete the job?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/ending-tuberculosis-save-millions}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.