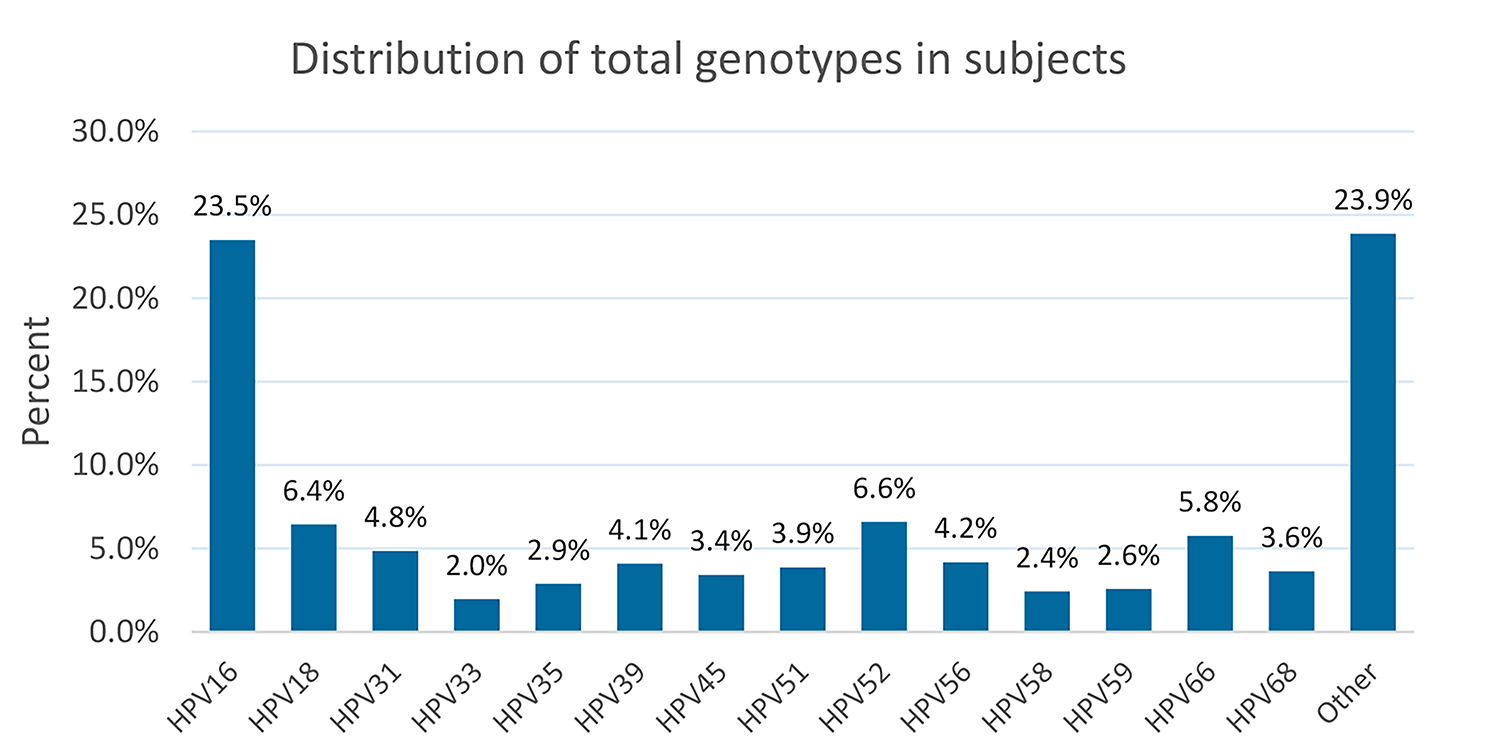

In this study, we analyzed data from 710 participants to explore the relationship between different HPV genotypes and the occurrence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). Our results showed that HPV-16 and − 18 genotypes had a statistically significant relationship with the increased probability of CIN, with an odds ratio of 2.88 and 1.87, respectively. Although HPV-31 and- -35 genotypes did not reach statistical significance at the 0.05 level, they were very close to the threshold, indicating a potential association. Additionally, we observed significant correlations between CIN and other factors such as smoking and Pap smear results, emphasizing CIN development’s complex and multifactorial nature. These findings could contribute to a better understanding of HPV-related cervical disease progression.

In the study conducted by Sánchez-Siles et al., individuals in the HPV-related CIN group had an average age of 34.54 years, with 30% reporting alcohol consumption and 42% being smokers. The most prevalent HPV genotype in this group was HPV-45 at 33%, followed by HPV-39 at 22%, and HPV-16 and HPV-56 at 11%. While the average age of participants in their study is similar to that of our research, we observed higher rates of alcohol consumption and smoking among our participants. Furthermore, in contrast to their findings, the most frequently reported genotype in the present investigation was HPV-16, nearly four times more prevalent than in their research. Significant discrepancies were also noted in the infection rates of other genotypes between our study and theirs [18]. Although the average age of the participants in their article was comparable to ours, we noted higher rates of alcohol consumption and smoking within our group. This suggests that lifestyle factors may contribute significantly to our subjects’ risk of developing CIN, emphasizing the need for targeted public health interventions that address these behaviors.

A piece of research focusing on women with cervical cancer in South Africa found that the most prevalent HPV genotype was HPV-16, accounting for approximately 35% of cases, followed by HPV-35 at around 17%, and both HPV-45 and HPV-54 at 12%. HPV-18 and HPV-52 represented about 11% and 10%, respectively. This suggests a potential consistency in the oncogenic risk posed by these genotypes across different geographic locations. The persistence of these genotypes underscores the necessity of targeted awareness campaigns and vaccination efforts that address these high-risk strains to mitigate cervical cancer risk. The average age of participants in the present survey was 42 years, indicating a difference of over seven years compared to the population in our study. This age difference may reflect regional variations in the demographics of cervical cancer patients and could influence the screening practices and healthcare access for women in these populations. Older patients may face different risk factors and healthcare challenges compared to younger individuals, complicating direct comparisons of HPV prevalence and its implications. When comparing the findings from this research with our results, we observe that the prevalence rates of HPV-16, HPV-18, and HPV-52 are relatively similar. However, the two studies have significant differences in the prevalence rates of HPV-35, HPV-58, and HPV-45 [19]. In our study, the prevalence rates for these genotypes differed markedly, indicating distinct epidemiological patterns that warrant further investigation. The higher prevalence of HPV-35 in the South African population might suggest regional variations in sexual behavior, HPV vaccination uptake, or socioeconomic factors that influence HPV exposure.

A survey conducted on women from Southern Mexico involved 253 participants with a mean age of 50, all diagnosed with cervical cancer. Among these women, 9% were confirmed smokers, with an HPV prevalence of nearly 99%. This discrepancy could be attributed to variations in lifestyle, cultural practices, or access to smoking cessation resources between the populations. The higher smoking prevalence in the present investigation may suggest an increased risk factor for cervical cancer, as smoking is known to exacerbate the effects of HPV and contribute to the progression of cervical lesions. The most common HPV genotypes identified were HPV-16 (approximately 65%), HPV-18 (10%), HPV-45 (7.5%), and HPV-31/-52/-58 (3.5%). Our findings show significant differences compared to our results; for instance, the smoking rate among participants in our observation was considerably higher. In addition, the prevalence of genotypes 31 and 52 in our observation was approximately three to four times that reported in this paper. This finding highlights potential regional differences in the circulating HPV genotypes and their associated risks. The increased prevalence of these genotypes in our cohort may reflect unique socio-demographic factors, sexual behaviors, or differences in HPV vaccination coverage. Understanding these variations is crucial for tailoring public health interventions and screening programs to effectively address the specific risks different populations face. Although the prevalence of HPV-16 was lower in our findings, the rates of HPV-18 and HPV-58 were similar across both studies [20]. This similarity underscores the importance of these genotypes in the cervical cancer landscape and suggests that they may pose a consistent risk across diverse populations. The presence of HPV-18, in particular, is noteworthy due to its established link to more aggressive cervical cancer forms, emphasizing the need for vigilant monitoring and targeted prevention strategies.

In a 2016 study by Piroozmand et al.(2016) conducted in Iran, the typing of HPV among patients with cervical dysplasia and cancer revealed that approximately 38% were infected with HPV-16 (versus 43.7% in our study), around 27% with HPV-18, nearly 15% with HPV-33, and 4% with HPV-31. The findings regarding HPV-16 are consistent with the results of the present survey; however, there are significant discrepancies in the prevalence of other genotypes between the two studies [21]. This higher prevalence might suggest that our population is experiencing an elevated risk of HPV-16-associated diseases, potentially linked to a variety of factors, including genetic susceptibility, sexual behavior, or access to healthcare services for screening and vaccination. The disproportionate incidence of HPV-16 in our study reinforces its role as a primary oncovirus in cervical cancer and highlights the need for targeted prevention strategies that focus on this genotype.

This Study showed that older patients had better CIN (low-grade) conditions than youngsters; the chances of having better CIN (low-grade) conditions were 1.2 times higher than those of lower ages. cultural transformations in Iranian society over the past two decades have influenced current epidemiological patterns. Historically, many women participated in monogamous relationships, which likely reduced their exposure to high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes. Additionally, limited public awareness and the high cost of HPV vaccines have led to low vaccination coverage. In many cases, individuals receive the vaccine only after they have been infected, which diminishes its preventive efficacy. These factors highlight the urgent need for culturally tailored public health interventions, including education, affordable vaccination programs, and accessible screening services.

This study, together with the finding that a higher sexual debut age was associated with lower chances of experiencing worse CIN conditions, highlighted the close relationship between the age of commencement of sexual activity and the incidence of cervical carcinoma. High-risk sexual behaviors, as well as high frequency of exposure to HPV during early reproductive periods, permit the virus to employ a hit-and-run scenario that ultimately leads to cervical cancer at older ages. These findings collectively underscore the necessity for region-specific strategies for cervical cancer prevention and control. Given the differences in smoking prevalence and HPV genotype distribution, public health initiatives should prioritize education on smoking cessation, promote HPV vaccination, and enhance screening programs tailored to the unique epidemiological profiles of local populations. Understanding these dynamics is essential for developing effective public health policies aimed at reducing the burden of cervical cancer and improving health outcomes for women globally.

This Study does have certain limitations and potential biases. Firstly, a larger sample size could have provided more insightful results and a broader perspective on the findings. Secondly, including additional information, such as family history and the assessment of secondary infections with other microorganisms, could have yielded more interesting data and offered new insights. Finally, due to the high costs associated with follow-up, we could not monitor patients to evaluate and report on the persistence or clearance of infections over time. Another limitation of the research is the lack of knowledge about the previous infections of the people. Considering that the occurrence of cancer in people takes time and has a much longer time frame than HPV, cancer may be related to the genotype that the person was previously infected with, but not associated with the current genotype. Therefore, we may obtain different results by considering the genotypes of previous infections.