Melioidosis is a recognized and increasingly prevalent infectious disease. However, whilst a significant body of work characterizes this disease in adult populations, little work has been done to explore this disease’s impact on neonates. This is the first PRISMA-compliant, and largest, systematic review of melioidosis infections in neonates conducted.

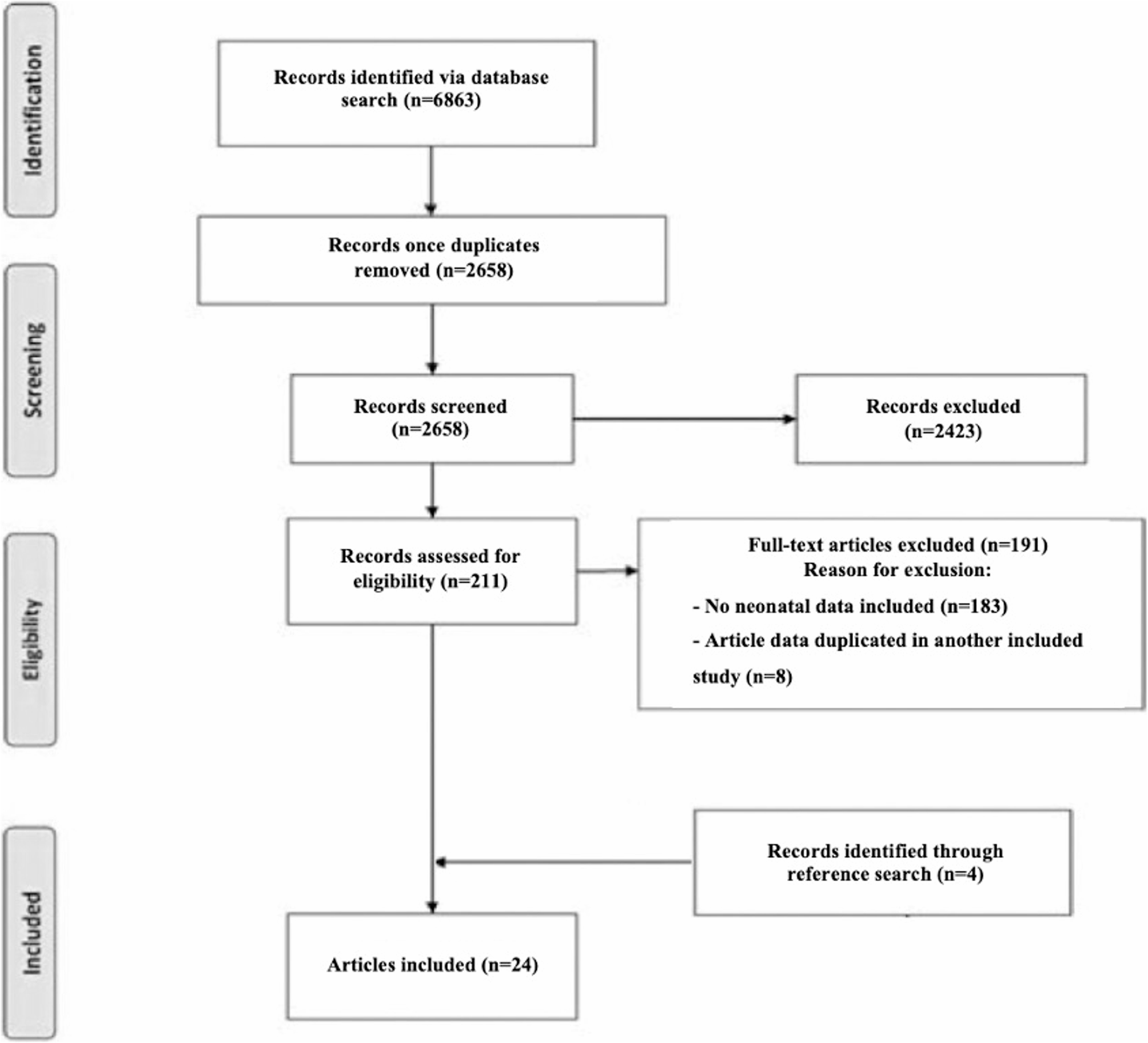

Our work identifies several key findings. Firstly, there is a significant lack of high-quality studies investigating melioidosis in the neonatal population. Whilst we identified 24 papers relevant to our review detailing a total of 50 cases, none of these offered stronger than Level 4 quality evidence. All studies were either retrospective case series with small sample sizes, or case reports. This likely reflects the rarity of this disease in neonates, which complicates attempts to both obtain larger samples, and to undertake prospective studies. Future studies should, therefore, focus on utilizing multi-centre recruitment to increase sample sizes.

Of the 24 papers identified, 5 had insufficient detail for meaningful synthesis of their included cases, significantly reducing the sample available for analysis. Standardization and improved quality of reporting practices is, therefore, needed to facilitate meta-analysis of collected cases.

Despite these barriers, however, our study identified several significant clinical outcomes of interest. Firstly, neonatal presentations of melioidosis appear to differ significantly from paediatric cases. Whilst a significant majority of paediatric infections present with localized infection, most commonly a cutaneous or parotid infection10, more than three quarters of patients in this review had disseminated disease on presentation (77%). This difference in symptomatology likely reflects both rapid progression of melioidosis in neonates, and different routes of infection across patient groups.

Our sample of 26 cases demonstrated a mortality rate of 65%, substantially higher than reported melioidosis mortality globally, which is estimated between 10% in regions with access to intensive care facilities and over 40% in regions with limited resources for diagnosis and treatment [43]. A 2021 literature review calculated the global mortality at 33.9% between 2016 and 2020 [44].

This highlights the need for awareness of these atypical presenting features, and that this cohort’s predisposition to present with advanced disease requires rapid antibiotic intervention.

Given this atypical presentation, it is unsurprising that our review also found a relatively low rate melioidosis diagnosis prior to patient death − 38% (10/26) of cases were only identified post-mortem. This finding may result from the lack of rapid diagnostic testing for melioidosis, and the rapid deterioration of neonatal patients. Development of a rapid diagnostic test for the pathogen would be an effective approach to accelerating diagnosis and therefore expediting appropriate antibiotic management. However, this technological advance would require funding and focus not currently enjoyed by melioidosis research. A more practical approach, therefore, should focus on increasing clinician awareness of the clinical presentation of neonatal melioidosis.

Greater awareness of possible vertical melioidosis transmission is also required. Our sample identified 3 proven cases of author-identified vertical transmission, and a further 3 in which, whilst no transmission was confirmed, the infant was symptomatic at birth. This suggests 6 cases of likely vertical transmission in our sample (23%), a higher rate than currently hypothesized. Whilst more thorough investigation is required to confirm this hypothesis, it suggests that screening of at-risk maternal populations, for example through routine vaginal swabbing and culture, might facilitate the early diagnosis and management advocated for above, for example using intra-partum antibiotics. Such strategies are currently employed to manage other neonatal infections, including Group B Streptococcus.

This review suggests that directed antibiotic treatment is effective in reducing mortality in neonatal melioidosis. International consensus on melioidosis treatment is based on the Darwin Melioidosis Treatment Guidelines, which advocate use of either ceftazidime or meropenem or imipenem during acute infection [8, 9]. 50% of infants receiving guideline-specified antibiotic regimens survived, and 50% of infants who received antibiotics following susceptibility testing also survived. However, a mortality rate of 90% was found amongst patients receiving neither melioidosis recommended or antibiotics aligned to sensitivity testing. This high mortality may be linked to melioidosis’ predisposition to developing latent infection and antibiotic resistance, increasing longer term risk of treatment failure and mortality following poorly targeted treatement [45]. Lack of follow up follow-up prevented assessment of long-term efficacy in this review.

Despite this, the rarity of melioidosis in neonates renders empiric use of antibiotics suited to melioidosis treatment inappropriate. Given the challenges of developing rapid diagnostic testing discussed above, this finding again supports the need for increased clinician awareness of neonatal melioidosis to expedite appropriate management.

This review also failed to identify any risk factors associated with melioidosis in neonates. Surprisingly, low birth weight and prematurity were not associated with neonatal survival.

Interestingly, we identified a higher incidence of male cases of neonatal melioidosis, mirroring a trend also seen in adult populations, where melioidosis incidence is 2 times higher in males than females15. Whilst this has been justified in adults as an occupation- related difference in exposure to the Burkholderia Pseudomallei pathogen [46], this explanation is not available amongst neonates. However, given the small sample size of this review, caution should be exercised before drawing any definitive conclusions from these findings.

Finally, the mortality rate associated with melioidosis in neonates (65%) appears to be substantially higher than that found in older children (7–20%) [47]. Several factors are likely associated with these poorer outcomes, including weaker neonatal responses to infection, the often disseminated state of the disease identified on initial presentation in neonates, and delayed use of correct antibiotics in neonates. That melioidosis prompts such high mortality in neonates, again, emphasizes the importance of future research aiming to improve outcomes in this population.

Melioidosis in neonates is a significant, and understudied, clinical problem. Further work should focus on generating: (a) higher quality data describing the diagnosis, management and course of melioidosis in neonates, (b) studies with larger sample sizes, likely requiring multi-centre recruitment given this pathology’s relative rarity, and (c) greater standardization of reporting to facilitate future evidence synthesis.

Establishing the incidence of neonatal melioidosis is of particular importance in guiding regional and national approaches to its epidemiological management. However, effectively estimating incidence would entail a protocolized approach to patient screening that would require significant research infrastructure and resources, which may well be prohibitive. Focus on conducting significantly sized retrospective studies to better characterize disease presentation, risk factors and course may be a more achievable goal for the near future.

Immediate priorities for improving outcomes in this cohort should be to improve clinician awareness of current melioidosis guidance, and the possibility of maternal melioidosis colonization as a risk factor for neonatal infection.

This review was limited by the poor quality of included literature, which largely consisted of case reports. Secondly, only a small sample of cases could be collected for discussion. Thirdly, the heterogeneity of reporting across studies prevented synthesis of all relevant outcomes. This review, therefore, should be understood as an overview paper seeking to stimulate discussion and raise awareness of the significant challenge posed by melioidosis in neonates.

It is also possible that our search methodology, which included reviewing the bibliographies of eligible publications to identify further eligible studies, may have introduced a citation bias [48]. However, we believe that the impact of this bias will be limited due to the thorough database searches initially performed for this review.

Finally, this review only included studies published in English. Given that melioidosis is most prevalent in non-English speaking regions, this review may therefore have failed to include a number of relevant studies.