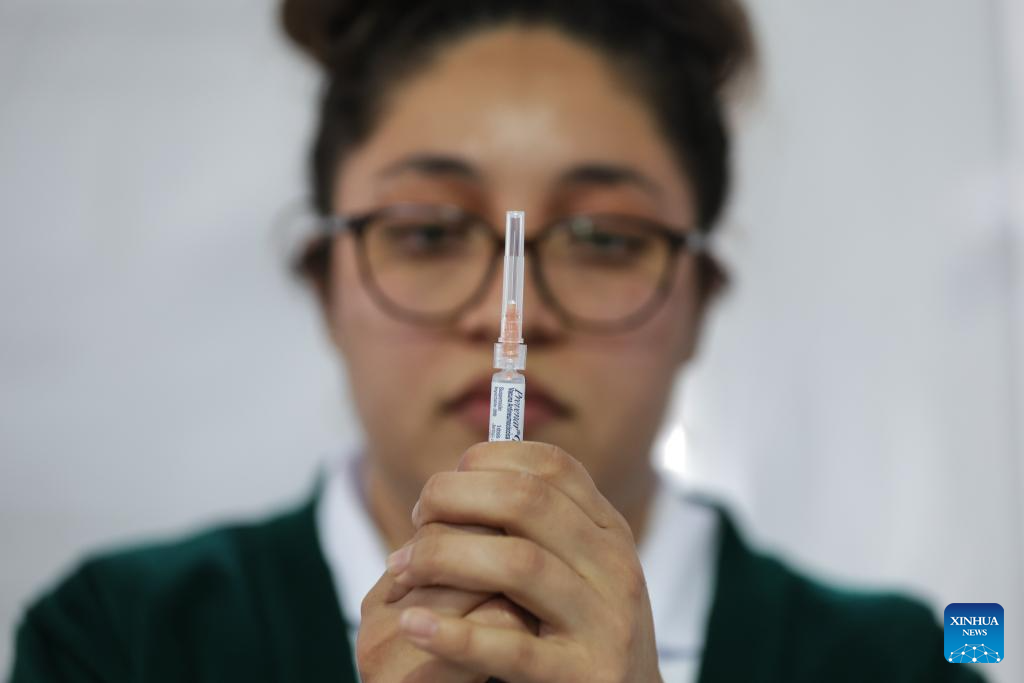

A health worker prepares to administer a vaccine at a vaccination center in Mexico City, capital of Mexico, Nov. 12, 2025. Mexico City has set up a vaccination center offering influenza, COVID-19, pneumococcal and measles vaccines to the public…

Mexico City takes measures to improve community immunization coverage during winter season-Xinhua