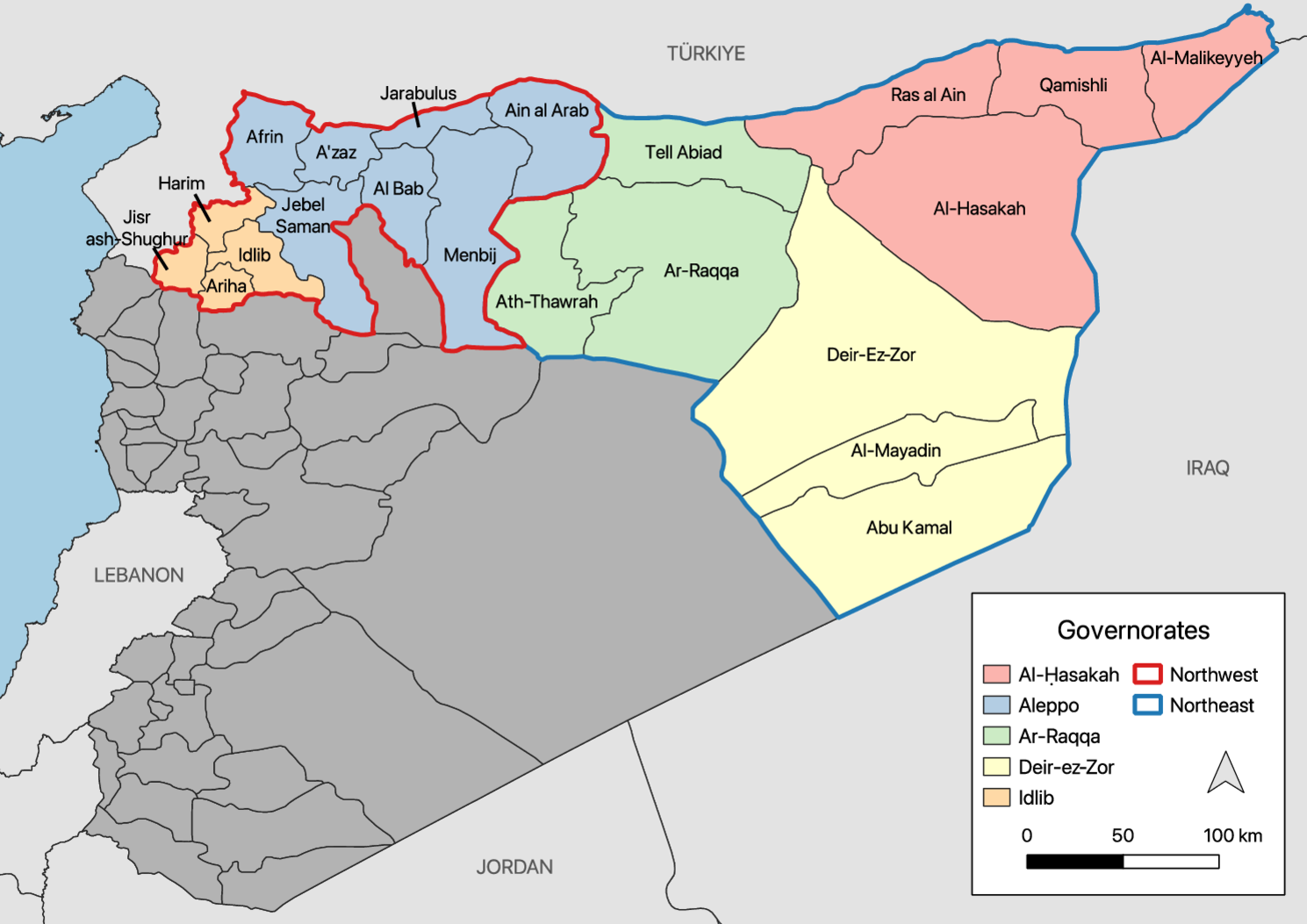

Conflict, environmental factors, and disease incidence are increasingly intertwined. Our study finds that several of the environmental factors evaluated were associated with changes in suspected diarrheal disease and respiratory infections in northern Syria, but in line with known biology, these associations were not often consistent between the two disease types. We also note that the combination of high levels of displacement and conflict was consistently associated with increased risk of both suspected diarrheal disease and respiratory infections, which accords with existing literature [42]. Syria has already experienced severe repercussions of climate change on its environment (e.g., through droughts, floods, and extreme heat), and this will likely continue in the future. We note that northeast Syria is particularly affected with higher temperatures in both the dry and wet seasons, less surface vegetation, and less surface water than northwest Syria; it is also more affected by interruptions of its key water stations, particularly Allouk water station. This may partially explain the higher proportionate morbidity, especially for suspected diarrheal disease, in northeastern governorates. Understanding the relationships between these environmental factors and infectious diseases, while also incorporating relevant conflict-related factors, is critical to prepare for changing disease burdens resulting from shifting environments. It can also help support regional and seasonal mitigation strategies given the localized differences seen in environmental factors and the burden of infectious diseases.

Mean temperature, precipitation, surface water, and vegetation levels are particularly relevant in the Syrian context. We found that increasing mean temperatures were associated with decreased risk of suspected respiratory infections but increased risk of suspected diarrheal disease across a lag period extending to 8 and 4 weeks respectively, which accords with prior work. There is a plausible biological-environmental mechanism for these relationships wherein, for instance, lower temperatures cause lower humidity and conditions facilitating respiratory transmission [43]. Warming temperatures in Syria have already largely outpaced global mean temperature increases (with no indication of cessation), indicating that risk of suspected diarrheal diseases may likewise increase [14, 15]. However, decreasing precipitation levels, which Syria has experienced since 1990, may increase suspected respiratory infection risk while decreasing risk of suspected diarrheal disease [10, 11]. We also found that vegetation levels were associated with reduced suspected respiratory infection risk in the same week but increased risk after 8 weeks. There are several possible explanations for this. Higher vegetation levels may create, over several weeks, environments that are more hospitable to disease spread. This could be through multiple pathways, including interactions with other environmental factors, increasing exposure to irritants (e.g., mold and pollen) that are risk factors for respiratory infections, or changing individual-level patterns, gradually increasing exposures and impacting health behaviors. The findings may also reflect different seasonality between NDVI and suspected respiratory infections, whereby their respective seasonal peaks occur at different times. While we account for seasonality with a week-of-year spline, there may be additional seasonality components that are meaningful to this relationship.

In Syria, as in elsewhere, it is important to note that changes in environmental factors are neither unidimensional nor consistent across time and space. While Syria is generally receiving less rainfall than before, there have been several instances of heavy rainfall (which likely also impacts vegetation levels) with widespread flooding, particularly affecting northwest Syria [44]. Such flooding may acutely increase the risk of suspected respiratory infections in the subsequent weeks, as pooled waters may harbor pathogens and other contaminants deleterious for respiratory health [45]. Flooding may also increase displacement and housing overcrowding in many contexts, which is an ideal context for respiratory transmission. This illustrates that when considering the potential effects of environmental events on disease incidence, long-term mean changes and as well as short-term climatic events must both be considered, as must unique spatial and temporal contexts. Likewise, it also highlights that certain diseases can be expected to increase by mode of transmission, according to changes in climate variables.

We also found the interaction between conflict and climate to be significant for both disease types. Conflict has been linked to increases in infectious disease risk throughout the literature, including in Yemen and Sudan [46, 47]. Though we tested each model with conflict and displacement modeled independently, we found that the interaction term produced a stronger model fit and is more consistent with the reality in northern Syria of intense conflict followed by mass displacement during the study period. Increased risk of suspected diarrheal disease at lower levels of conflict and displacement may be triggered by single but large-impact conflict events relating to destruction of water-related infrastructure, which could have a rapid effect on both displacement and waterborne disease cases. Allouk water station in Al-Hasakah is one example of this. The water station serves over 460,000 individuals in northeast Syria yet has faced recurrent direct attacks, discriminatory operation by the Turkish government (e.g., the station was cut off for five days in 2020 without reason), and its use in bargaining. This politicalization impeded the response to the 2022–2023 cholera outbreak in the region as regions downstream of Allouk were unable to access adequate water [48,49,50].

Two strengths of the study include biologically plausible findings and high explanatory power of the variables used. However, this study does have its limitations. The surveillance data used captures suspected but not laboratory-confirmed cases of disease amongst those persons who have access to health care, and is therefore biased against the specificity of case definitions in favor of the sensitivity of disease detection. In this exploratory analysis, we considered environmental variables and their lags individually in our model and did not consider any potential interplay between them. Future work should consider a conceptual causal model in evaluating linkages. The environmental variables may represent similar impacts on disease incidence due to their linkages in the causal chain. For instance, increased humidity may be a consequence of increased precipitation and exhibit a single effect. Each model was initially run with all environmental variables and their lags specified non-parametrically, though few exhibited non-linear behavior and thus we opted to specify them linearly to increase the models’ interpretability.

This study also uses a coarse measure of displacement, based on the available governorate-level data, that required several assumptions to move from a monthly governorate-level measurement to a weekly district-level. We evenly distributed the total reported monthly displacement for each governorate across each week and district within that month and governorate; this loses any variation between weeks or between the districts within a given governorate that may have affected incidence. Such spatial and temporal smoothing may obscure differences relevant to disease transmission and thus bias our results. However, it reflects our desire to capture displacement levels relative to districts over a multiyear time series, and we anticipate that this did not severely impact our results. However, future work that looks at these relationships (across environmental factors, conflict, and displacement) at smaller spatial scales would be important should those data become more readily accessible. Lastly, there may be other relevant variables within the causal chain, such as socioeconomic factors and conditions of displacement settlements, that would likely impact disease dynamics but that we were unable to capture.

The December 2024 fall of the Assad regime and subsequent establishment of a transitional government has undoubtedly moved Syria into a new era. Crucial to this transition will be the creation of robust and resilient healthcare and surveillance systems that can respond to the complex health needs of a population subjected to over a decade of violent conflict. This also presents a rare opportunity to plan for Syria’s future, which can include emerging strategies relating to climate change and disease prevention. Raleigh et al. (2024) have explored the possibility of climate change adaptation interventions relating to natural resource management, climate-smart agriculture, and drought-control measures, underpinned by community-led initiatives and local governance that could be appropriate for fragile, conflict and violence-affected countries [51]. In Syria, this can be informed by research that focuses on evaluating the forecasting capacity of environmental prediction variables, permitting anticipatory action for epidemic prevention according to long-term changes in climate variables and acute climate-related events [52].

Preparedness efforts that focus on climate change adaptation, with an emphasis on those relating to precipitation and temperature changes, will be important in this region. Syria currently does not have a formal climate change adaptation strategy [53], and the implementation of any future adaptation measures would require a revitalization of international financial support for the region [54]. Increased infectious disease risks are only one of several expected deleterious outcomes of these interplays. Malnutrition, livelihood generation, and the availability of habitable land have already been impacted by climate change and will continue to be so; each of these will also have direct impacts on individuals’ disease susceptibility. Though integrating climate considerations amidst ongoing violent conflict – and now a transitioning government – is certainly not ideal, it is necessary [55]. Such actions, in conjunction with ongoing advocacy and accountability efforts related to conflict, can work toward reducing the suffering experienced by Syrians, many of whom have only known these conditions.