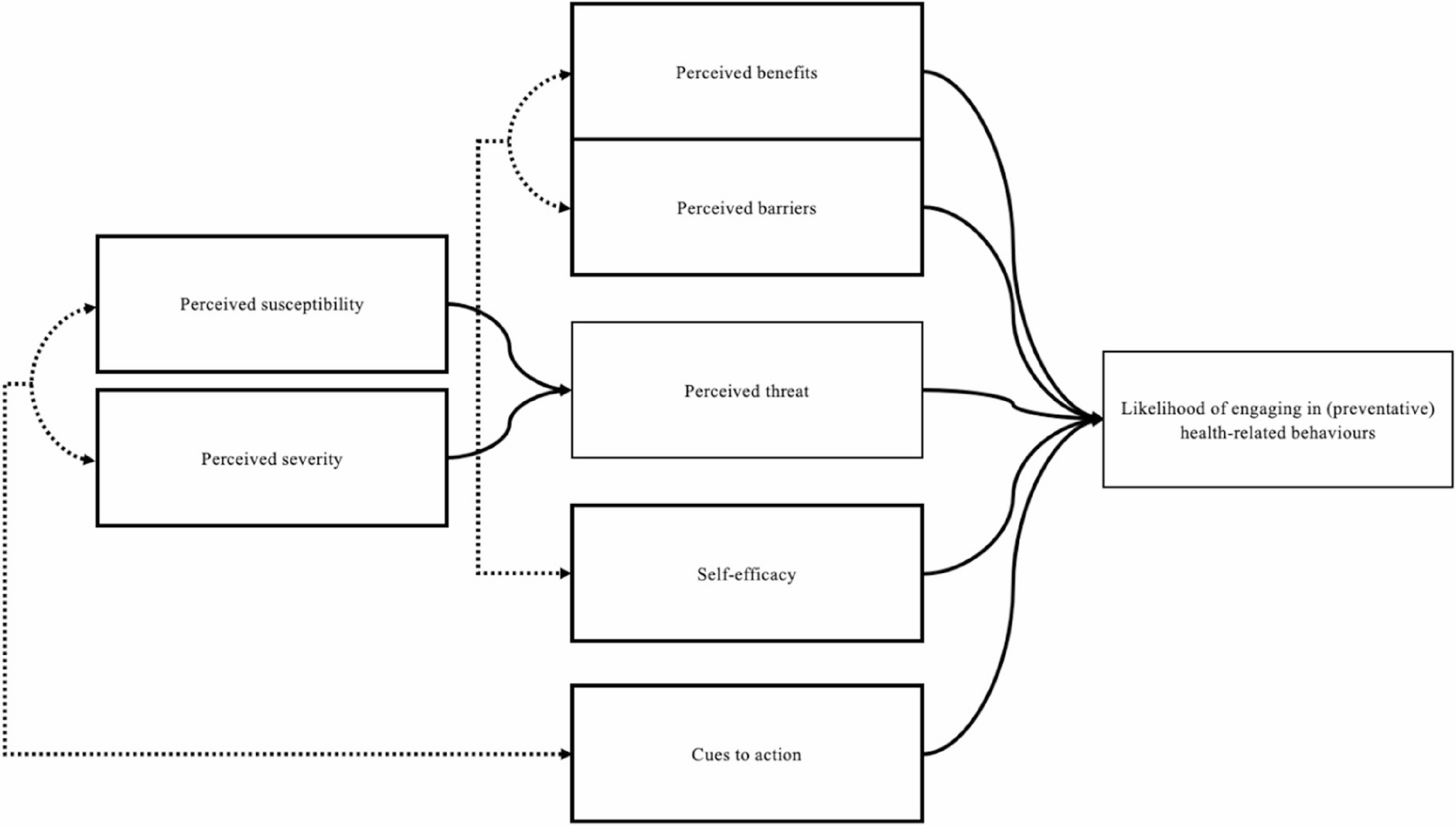

The findings of this paper provide critical insights into the social, cultural, and structural factors that shape young South Africans’ understanding of hypertension and their perceptions of prevention. The HBM concept of perceived threat (i.e., perceived susceptibility and perceived severity) suggests that individuals are more likely to take preventive action if they recognise a health threat as serious and as something they could develop [19, 20]. For many youth in this study, the low perceived severity of hypertension acted as a barrier to behaviour change despite youth perceiving high susceptibility. Although participants recognised their likelihood of developing hypertension in the future, participants in this study largely viewed their youth, good health, and lack of diagnosis as protective factors against threat of hypertension. This perception aligns with Elkind’s [21] concept of adolescent invincibility, which has been linked to a greater likelihood of engaging in risk behaviours [22]. This creates a paradox in how South African youth perceive hypertension, as while they view it as an inevitable part of their future, they do not see it as an immediate threat to their health, leading to a reluctance to engage in preventative or management behaviours.

Stress was also identified as a key psychological factor that further influenced participants’ lack of engagement with hypertension prevention. While few participants described hypertension itself as a major current stressor (often viewing it as a condition that affected “older people”), many acknowledged that stress more generally was prevalent in their lives and believed it could contribute to future health problems, including hypertension. In this context, some participants described deliberately avoiding thoughts about hypertension, as they believed that focusing on it could increase anxiety or even exacerbate the condition. This tendency to mentally distance themselves from health risks can be understood as a coping strategy aimed at emotional self-regulation. Rather than reflecting fear or active distress about hypertension specifically, these responses appear to reflect a pattern of cognitive disengagement: an effort to reduce psychological discomfort associated with confronting long-term health risks while navigating already stressful life circumstances. This aligns with the concept of avoidance coping, a strategy in which individuals manage distress by denying or distracting themselves from a health threat rather than actively addressing it [23, 24]. Evidence from South Africa shows that avoidance coping strategies (such as denial, distraction, or minimising perceived risk) play a critical role in shaping maladaptive health-related behaviours, as seen in people living with HIV, where internalised stigma predicted higher avoidant coping, leading to delayed antiretroviral therapy initiation and poorer health outcomes [23]. Similarly, in the context of hypertension, avoidant coping may diminish proactive health-seeking behaviours, reinforcing disengagement from prevention and treatment. Participants described distancing themselves from the risk of hypertension by emphasising their young age and perceived good health, avoiding health information they found confronting, or deferring lifestyle changes to a distant future. Chasiotis et al. [24] further highlighted that avoidant motivation reduces engagement with health information-seeking and problem-focused coping, leading instead to emotion-focused coping strategies such as denial or distraction rather than direct disease management and prevention. In this study, participants demonstrated these avoidant coping patterns through a preference for stress management practices, such as meditation and breathing exercises, rather than direct engagement with hypertension prevention strategies. While these approaches contribute to overall well-being, they may also serve as a form of psychological distancing. By focusing on managing stress in general rather than addressing specific behavioural risk factors (such as diet, physical activity, or blood pressure monitoring), participants may unintentionally reinforce inaction toward meaningful risk reduction. This indirect approach reflects a broader coping style oriented toward emotional relief rather than problem-solving, thereby limiting the likelihood of sustained health-promoting behaviours.

In addition to stress, this study found that some youth (particularly female youth) viewed a healthy lifestyle in terms of drinking water and a healthy diet as something “only for white people”. This perspective reflects how racial and cultural identities influence health behaviours, particularly in South Africa which where the legacy of apartheid continues to shape perceptions of health and wellness [25]. The transition from apartheid to a democratic society has resulted in a complex interplay between modern, Western health practices and longstanding traditional practices [25]. Within this context, some participants viewed health-promoting behaviours as culturally alien or associated with a racialised identity, contributing to resistance in adopting such practices. This perception is particularly significant given the documented links between poor dietary patterns and the prevalence of diseases like hypertension. These dynamics are not unique to South Africa; studies in England have similarly shown that cultural values and traditional food beliefs significantly shape health behaviours among minority groups [26]. Public health interventions often fail to resonate with these groups when they are not culturally adapted, ignoring the role of traditional foods, taste preferences, and social meaning of eating [26]. This underscores the need for culturally responsive health strategies that account for the socio-cultural context in which health behaviours are developed and sustained.

Further to the social and cultural influences, peer pressure also played a significant role in shaping participant’s health-related behaviours. Literature suggests that adolescent males, in particular, exhibit increased risk-taking due to a stronger peer group orientation [27]. In this study, however, both male and female participants described engaging in unhealthy behaviours (such as drinking alcohol, eating unhealthy foods or skipping exercise), not out of personal preference but as a way to maintain social inclusion. Several youth expressed fear of being judged, excluded, or labelled as “boring” or “different” if they made healthier choices. These accounts underscore how peer norms can create a powerful incentive to conform, often overriding individual efforts to adopt healthier behaviours. In such contexts, social belonging was often prioritised over long-term wellbeing, highlighting the importance of addressing peer dynamics in youth-focused health interventions.

A culture of social gatherings centered around high-calorie, processed foods, and limited physical activity reinforced these patterns of unhealthy lifestyle behaviours, such as frequent consumption of unhealthy food, habitual sedentary leisure activities, and the prioritisation of social acceptance over personal health. Some traditional cultural practices, such as the expectation to consume large portions of energy-dense foods during family or community events, were perceived as contributing to health risks. In line with findings from Buksh et al. [28]participants in this study also shared that overconsumption of food during social gatherings was common and often encouraged. Social norms played a powerful role in shaping both dietary and physical activity behaviours, as supported by a recent systematic review which found that such norms consistently drive directional changes in youth behaviour [29]. This is particularly important given that opportunities for physical activity are not always within the control of young people. According to the Theory of Expanded, Extended, and Enhanced Opportunities (TE), youth often have limited automony over when, wehere, and how they are pgysically active due to to the structured environments in which they live [30]. Without intentiaonl efforts to expand, extend, or enhance these opportunities, and to ensure youth are supported and motivated within them, it becomes difficult for healthy movement behaviours to compete with prevailing sedentary norms. As Monterrosa et al. [31] note, food choices are deeply influenced by cultural, social, and psychological factors, making dietary patterns both a personal and social expression of identity. This complex web of influences highlights the difficulty of adopting healthier eating habits in environments where traditional and social expectations outweigh concerns about nutritional health.

Many participants learned about hypertension through observing family members or neighbours, with their views influenced by how those around them managed, or failed to manage, the condition. For some, hypertension was perceived as a minor, manageable issue, particularly when individuals neglected medication adherence yet appeared to function normally. This was especially true for those who remained asymptomatic, mirroring findings from Jimmy & Jose [32]which highlight that non-compliance with chronic disease medications is most common when patients do not experience unpleasant symptoms. In fact, medication adherence rates for chronic conditions like hypertension often drop significantly when symptoms are absent, as patients perceive the disease as less urgent or severe. As a result, some individuals became complacent and skeptical about the true severity of the disease. This also aligns with Nouhravesh et al. [33]who observed that asymptomatic participants often did not perceive their condition as a real threat, showing little effort to understand or manage it until symptoms appeared, further contributing to a false sense of security regarding the potential risks of hypertension. However, others who had witnessed serious complications, such as strokes, kidney failure, or premature death, regarded hypertension as a significant and life-altering condition.

A major challenge identified by youth was the secrecy surrounding hypertension in their families and communities. Participants noted that older relatives often concealed their diagnosis, rarely spoke about the condition, or disclosed it only after severe health events such as strokes or death. This silence around the disease left youth without firstand exposure to what living with hypertension entails, limiting their understanding of its long-term consequences. Many interpreted the secrecy as rooted in stigma; specifically, fear of judgement or perceptions of weakness, which created cultural taboos around discussing chronic illness. This dynamic mirrors findings in studies of dementia-related stigma in South Africa, where internalised shame and fear of social rejection led families to avoid disclosure and isolate affected individuals [34]. For youth in this study, such patterns of silence contributed to a low perceived threat of hypertension and weakened motivation to engage in preventive behaviours. Without visible role models openly managing the condition, hypertension remained abstract and distant; as something that happened to ‘other people’ or only became relevant in old age.

Participants frequently discussed how family members shaped their food choices and health habits, both positively and negatively. Some shared that when parents prepared meals or encouraged exercise, it was easier to adopt and maintain healthy behaviours. Family structures and systems are essential in shaping food choices, as they establish the foundation for lifelong eating habits [31]. These food practices are primarily learned through the transmission of behaviours and norms from parents to children, influencing not only what is eaten but also how and when meals are consumed [31]. When families model and encourage healthy behaviours (such as preparing nutritious meals, promoting balanced diets, and supporting physical activity) youth found it easier to adopt and sustain these habits [31]. However, other participants described family environments where unhealthy eating patterns (such as frequent fried foods or sugary drinks) were the norm, and attempts to eat differently were dismissed as strange or ungrateful. Youth highlighted the tension between wanting to change and the difficulty of doing so in households where health was not prioritised. When unhealthy patterns were normalised, or when support for change was lacking, participants reported significant barriers to making healthier choices. This dynamic is especially relevant in the South African context, where many youth continue to live at home and are deeply influenced by their families’ attitudes and behaviours. As noted by Bottorff et al. [35]the family unit plays a crucial role in shaping healthy behaviours, especially in childhood, by providing opportunities for physical activity and healthy eating. While their study focused on children, this dynamic remains relevant for youth, as family caregivers continue to shape lifestyles choices and help address modifiable risk factors, such as poor diet and physical inactivity, that contribute to long-term health issues like hypertension. This is applicable to the current study, which shows how family norms, modelling, and support systems can either enable or constrain youth’s ability to adopt preventative behaviours, underscoring the importance of targeting family dynamics in youth-focused health interventions.

These results highlight the complex, multilevel factors that shape food and lifestyle related choices, where interactions between youth and their environment influence health-related behaviours [31]. While environmental factors, such as food marketing and availability, play a crucial role, biological factors like innate preferences for sweet, salty, and high-fat foods (which are deeply rooted in our biology) also drive individuals toward unhealthy options [36]. The food industry exacerbates this dynamic by marketing highly palatable, energy-dense foods that stimulate pleasure receptors in the brain, reinforcing unhealthy eating habits [37]. Youth in this study described pervasive advertising for fast food and sugary drinks as a persistent external cue, normalising unhealthy consumption and making it harder to prioritise healthier options. Broader structural factors, including limited access to affordable healthy food, lack of fitness resources, and societal norms favouring convenience over health, create systemic barriers to adopting healthier lifestyles. Additionally, barriers to healthcare access, such as long wait times and a focus on treatment (medication) rather than prevention, deter youth from engaging in proactive health management, with perceptions that clinics are only for severe illness further delaying the adoption of preventative care [38]. These combined factors contribute to unhealthy dietary behaviours and limited engagement with health-services, increasing the risk of hypertension in South African youth.

Lastly, the findings of this paper demonstrate that youth are looking to community structures such as schools, churches, clinics, and government institutions in supporting youth efforts to adopt healthier behaviours. Participants emphasised the need for greater dissemination of accurate health information and the creation of environments that actively facilitate positive change. While churches are highlighted in this paragraph to illustrate the role of these institutions, the findings can also be applied to schools, clinics, and government organisations, as they share a similar potential to influence health outcomes. Evidence, such as the Impilo neZenkolo (‘Health through Faith’) programme [39]demonstrates the potential of church-based interventions to address health challenges in lower income communities. Further to this, churches have also played a key role in promoting health in South Africa, as seen in HIV prevention efforts [40]underscoring their potential as important partners in public health initiatives. However, while structures such as churches hold promise as powerful agents of health promotion, participants also acknowledge their capacity to spread misinformation when not used correctly. Churches, for example, were identified by participants as both a source of guidance and a barrier; while some invited health experts to educate congregants on disease prevention and healthy living, others promoted the idea of praying illness away. Expanding on the former point, in this study, youth advocated for the inclusion of diverse stakeholders, and emphasised the importance of moving beyond one-size-fits-all health campaigns. They call for collaborative efforts that engage influential community figures such as doctors, religious leaders, media personalities, and government officials to co-create sustainable and meaningful preventive health initiatives.

Limitations

This study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting. First, as a qualitative study conducted in a specific urban context (Soweto), the findings are not intended to be generalised to broader populations. Instead, their transferability depends on the relevance and resonance of the themes within similar sociocultural and economic settings. While the sample offers rich insights, participants were drawn from a single urban area, which may limit the applicability of the findings to rural areas or other South African communities with different contextual realities. Second, although social desirability bias is a known consideration in qualitative research, this study is further shaped by the dynamics between interviewer and participant. Interviews were conducted by trained researchers with local contextual understanding, but differences in age, gender, or perceived authority may have influenced participants’ willingness to disclose sensitive or socially undesirable information. Reflexivity was practiced throughout data collection and analysis; however, the influence of researcher positionality and the interview setting on data richness and disclosure remains a limitation. Lastly, while the cross-sectional design aligns with the explortatory goals of qualitative inquiry, it limits the study’s ability to capture changes in young people’s perceptions over time. Youth perspectives on hypertension and prevention behaviours may evolve due to shifting life circumstances, social influences, access to new information, or changes in health status. Further longitudinal qualitative research could explore how these perceptions are shaped and reshaped over time.