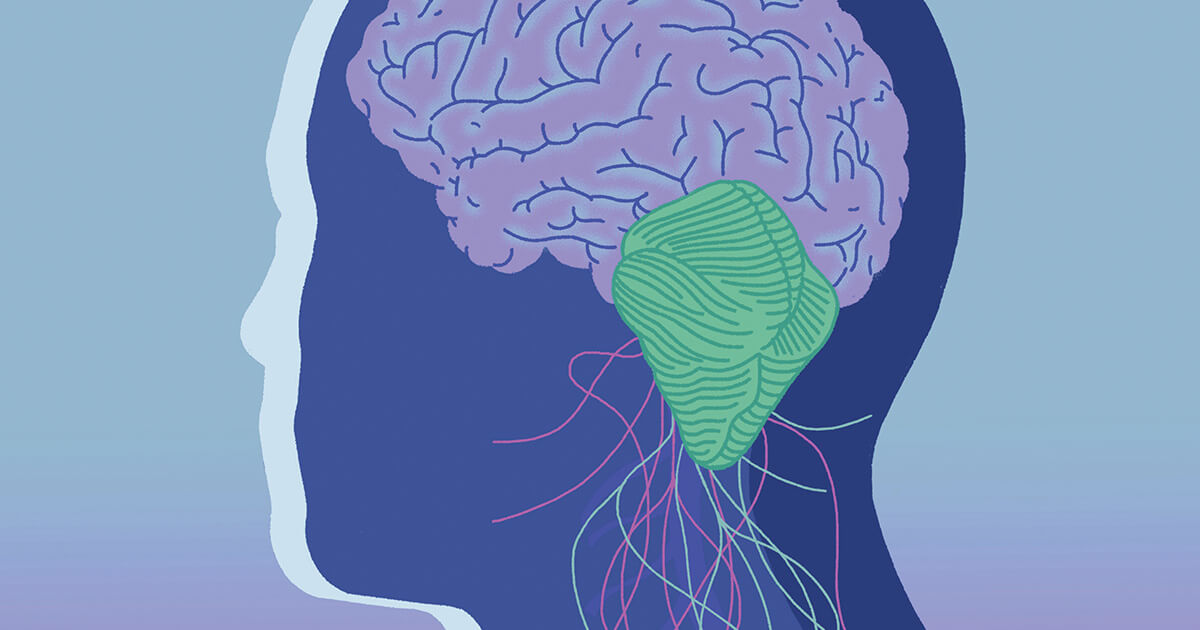

When Rick Labuda was 31 and expecting his first child, his wife pushed him to finally seek medical care for long-ignored symptoms that included intense, exertion-induced headaches; constant neck pain; and an atrophying right shoulder. After an X-ray of his neck revealed a congenital fusion of his skull and top vertebra, a subsequent MRI led to a diagnosis of type I Chiari malformation. In this condition, the bottom part of the cerebellum, known as the cerebellar tonsils, protrudes through the foramen magnum, the hole at the base of the skull where the spinal cord enters.

Things happened fast following Labuda’s diagnosis. He met with a neurosurgeon, who conducted a number of tests, such as seeing if he could balance with his eyes closed, feet together, and head tilted back. “It was quite a shock to see that I couldn’t pass basic neurological tests and that I would need to have surgery to resolve my problems,” he recalls.

Labuda had surgery about four months after his diagnosis, shortly following the birth of his daughter. He went back to his job in tech within weeks, though over the next few years, he found that shoulder and neck pain made it increasingly difficult to continue working in a traditional office. “My life was difficult afterwards, because I still had Chiari-related nerve damage even though the surgery stopped the progression of symptoms,” he says.

Within a few years of surgery, Labuda left his career so he could focus more on his recovery. He’d begun devoting more and more time to researching Chiari, and in 2004, he started a nonprofit called Conquer Chiari. Now 57 and with three grown children, Labuda lives with his wife near Pittsburgh and is the organization’s executive director. “My pain is no longer constant, and I’m doing very well, but it was a long road,” he says. “I believe it’s important for patients to try and find purpose and set up a life situation that enables them to focus on the things most important to them.”

Headaches and More

Chiari is a complex condition that has two broad consequences, according to Robert Friedlander, MD, chair of the department of neurological surgery at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine: the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cannot flow as it should, and pressure is put on the spinal cord. CSF blockage causes intermittent, increased pressure on the brain and leads to headaches in the back of the head, which affect the occipital nerves running through the scalp. Labuda experienced these headaches, which Dr. Friedlander called the cardinal symptom of Chiari. Coughing, sneezing, or straining can worsen headaches near the base of the skull, he adds.

The second most common Chiari symptom is numbness and tingling in the extremities, the result of pressure on the spinal cord. Other potential symptoms include balance issues, neck pain, and muscle atrophy, like Labuda experienced. Some patients may experience tinnitus or ringing in the ears, swallowing and breathing difficulties, mild cognitive problems, and vision issues.

No concrete explanation exists for why Chiari-related symptoms can vary so much. Dr. Friedlander says some patients whose Chiari looks severe on MRI don’t have symptoms, while others whose Chiari looks mild may have severe symptoms. After performing more than 500 surgeries, he says he and others “are beginning to find that some people have membranes, known as embryological remnants, that aren’t visible on MRI and which could obstruct the flow of CSF to varying degrees.”

There are two categories of Chiari: congenital and acquired. In the congenital form, Dr. Friedlander says patients are born with an abnormally small posterior fossa—the cavity at the base of the head—and the cerebellum essentially gets pushed out because it does not have enough room. “Some people are born with it but do not have symptoms until later in childhood or even adulthood,” he adds.

He suspects a correlation likely exists between a small trauma and onset of the condition. “It’s not fully understood, but when patients are born with the congenital form and don’t develop symptoms until 30 years old, you ask yourself why,” Dr. Friedlander says. “There is likely something like a fall or some other event that triggers the cerebellum to sag a bit more.”

Acquired Chiari, meanwhile, occurs for two possible reasons: pressure from above the foramen magnum, like a tumor or hydrocephalus, or pulling from below the foramen magnum, such as a CSF leak or a tear in the dura, the outermost layer of the membranes that surround and protect the brain and spinal cord, he says.

In addition to these broad categories of Chiari, the condition has four classifications. According to the National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke, the vast majority of patients have type I, the mildest form. Type II, sometimes referred to as Arnold-Chiari malformation, usually includes a form of spina bifida (a birth defect in which the spinal cord and spinal bones do not close completely while developing) and both the cerebellum and brainstem extending into the foramen magnum. Types III and IV are the rarest and most severe; in type III, both the cerebellum and brainstem protrude through a hole in the skull, and type IV involves an incomplete or underdeveloped cerebellum.

While surgical techniques have evolved some since Labuda was treated more than 20 years ago, surgery remains the only treatment for symptomatic Chiari malformation. The condition “is a mechanical problem because part of the skull doesn’t have enough room, so it needs a mechanical solution, which is to give that area more space,” Dr. Friedlander says.

Before surgery occurs, however, neurosurgeons say it is critical to rule out other explanations for symptoms that may be linked to other issues. Edward Ahn, MD, a pediatric neurosurgeon and chief of pediatric neurosurgery services at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, says while between 1 and 3 percent of all brain MRIs will technically show a Chiari malformation, it may not be the cause of a patient’s brain-related symptoms. “The challenge as a clinician is delving deep into a patient’s symptoms in order to discern whether the problem is due to the malformation,” he says.

If surgery is deemed appropriate, Dr. Friedlander says the two- to three-hour procedure for Chiari malformation is safe, and new approaches have made it even safer. In general, the process involves making a small incision near the base of the skull that goes down between the muscles and exposes the occipital bone down to the foramen magnum. From there, the arch of the C1 (first) vertebra is exposed so it can be shaved enough to allow for decompression. Though surgeons may remove the entire C1 arch in Chiari surgery, Dr. Friedlander prefers the shaving method because it’s a smaller operation that causes less pain and reduces the risk of spine instability, a rare occurrence.

In addition to bone decompression, Dr. Friedlander also opens the dura, uses electrocautery to reduce the size of the cerebellar tonsils to relieve pressure, and separates them so he can assess whether a patient has Chiari-related arachnoid adhesions or membranes blocking the free flow of CSF. “I don’t believe the patient has been fully treated unless all pathways are opened to ensure free flow of CSF,” he says. (He also acknowledges that some controversy exists among Chiari experts about the extent of the surgery.)

While Labuda spent five days in the hospital following his surgery, today Dr. Friedlander says his patients typically stay just one or two nights before being discharged. He recommends they take things easy and avoid any straining or lifting more than 5 to 10 pounds for about six weeks. “We see them two weeks after surgery, and if there are no issues, we see them again in six months for an MRI,” he says. “Most people are fine, never need to come see me again, and have a normal life.”

Chiari Malformations in Children

While most Chiari malformation diagnoses occur well into childhood or adulthood, Heather Nebel’s son, Carter, showed symptoms at birth. Hours after he was born, doctors were concerned with his fast-paced breathing and soon diagnosed him with aspiration pneumonia, a condition they told her can develop as newborns breathe in fluids during birth. But his symptoms grew in the following weeks to include frequent coughing and gagging, which often woke him up when he was sleeping and terrified his mother.

It took more than 10 challenging months filled with numerous hospital stays, continued choking, missed milestones (including the ability to eat solid food), sleep and breathing studies, appointments with specialists, and even an unnecessary surgery for “floppy epiglottis” before an MRI confirmed a diagnosis of Chiari malformation.

“The doctor wrote it on the back of a business card because there was no pamphlet, and she told me not to Google it,” Nebel recalls. “That was mind boggling to me, because she also scheduled us to see a neurosurgeon the next month. I remember being very scared and upset but also happy we knew what it was.”

Dr. Ahn says the manner in which Carter was diagnosed is atypical: “More commonly, children are older, involved in activities, and can tell us about the characteristic headache in the back of their head.”

Despite Carter’s unusually early diagnosis, Dr. Ahn says the boy’s symptoms were typical for Chiari. “When the cerebellum compresses structures because the space is too small, one of those structures could be the brainstem, which controls basic functions like swallowing and breathing,” he notes.

Carter underwent surgery within months of his diagnosis, and though Nebel called the experience harrowing, “the minute he woke up, I noticed he wasn’t choking and gagging, and he ate a Teddy Graham the nurse brought him. Within days, he ate everything in sight, and new worlds were opening up.”

Now 14, Carter mostly lives like a typical teenager, enjoying family activities, weekend camping trips, choir and theater practices, and hanging out with friends. However, he does still have some Chiari-related symptoms, such as difficulty regulating his body temperature, leg pain, low muscle tone, headaches, and slow processing time, which prompted him to do school from home this year. “It’s different, but now he has more energy to focus on his work rather than having to put so much effort into switching classes,” Nebel says.

From diagnosis to daily life, Labuda and Carter have had different experiences with Chiari, and others living with the condition likely have their own unique story to share. Lack of awareness among both patients and physicians continues to be a problem, however, and Dr. Friedlander recently published a review in the New England Journal of Medicine he hopes will help patients get a correct diagnosis more quickly.

“Some people have had typical Chiari symptoms for years but haven’t been diagnosed because many doctors don’t know about it,” he says. “While Chiari doesn’t kill patients, it has a great impact on quality of life, and surgery can greatly improve that.”

Patient Resources