When Celia Fairbanks fell down several times after getting out of bed one morning in late April 2025, she thought she was having a bad reaction to an antibiotic she’d been given for an infected insect bite the day before. “I called the nurse from my primary care office, and while I was on the phone with her, I started slurring my words, and the words I wanted to say in my head weren’t coming out of my mouth right,” says Fairbanks, a 28-year-old history student from Gaithersburg, MD. “So the nurse told me to hang up the phone and go to the ER right away.”

At Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, MD, she underwent several MRI scans. Doctors soon told Fairbanks she was having a stroke, with a clot blocking a blood vessel in her brain. They quickly administered tenecteplase (TNK), a clot-busting drug that restores blood flow and significantly improves outcomes in acute ischemic stroke.

“Within five minutes, I started feeling better,” says Fairbanks, who has a genetic predisposition for clotting and developed a blood clot as a teenager. “From not being able to say words and being totally out of it, I was completely back to normal. They kept me under observation in the ICU for 24 hours and repeated the MRIs, which showed that the clot was still there, but it was much smaller, and it was moving and not blocking blood flow anymore.”

Fairbanks walked out of the hospital fully recovered just one day after the stroke, thanks in large part to four decades of research led by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). The institute, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), celebrates its 75th anniversary this year. NINDS conducts and supports a wide range of research in neuroscience and neurology, driving discoveries that have advanced our understanding of how the brain works and led to powerful treatments.

“The past 75 years of NINDS have been completely transformative for neurologic research,” says S. Andrew “Andy” Josephson, MD, FAAN, professor and chair of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. “Research that NINDS has supported extends from the most basic science and fundamental understanding of the nervous system to clinical trials of drugs and other therapeutics, which have provided cures and effective treatment for so many neurologic disorders. Without NINDS, these important therapies never would have come to fruition.”

One of those therapies is TNK, the drug that almost instantly broke down Fairbanks’ clot and resolved her stroke symptoms. In December 1995, a NINDS-sponsored trial of a thrombolytic—a medication that dissolves blood clots—called tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) led to the approval of the first treatment for acute stroke. TNK, which has similar outcomes with a more convenient administration protocol, has since replaced tPA as the preferred emergency stroke medication.

“Previously, stroke was a disease with no treatment at all, and many organizations did not want to invest in finding treatments because of the belief that it was too hard to crack,” Dr. Josephson says. “NINDS stepped forward and funded pivotal trials, including that of thrombolytics, that have helped save millions of lives and prevented the kind of disability that we all hope we will never have.”

And NINDS played another role in Fairbanks’ recovery. As a younger patient with relatively mild symptoms—her score on the NIH Stroke Scale was only a 1 out of 42—suspicion that she was having a stroke was relatively low. “They could so easily have just said, ‘You’re young. You probably have a cold or the flu, and you’re just out of it. Go home and take it easy,’” Fairbanks says.

But since 1999, Suburban Hospital has collaborated with NINDS to evaluate using MRI to assess patients with signs of stroke and identify who can benefit from clot-busting drugs even if their symptoms seem mild—as well as patients like Fairbanks who don’t know the time their strokes began. The sooner treatment starts, the more effective it is.

John Lynch, DO, MPH, the stroke neurologist who treated Fairbanks, leads that collaboration. “Our work has identified specific markers on MRI that were associated with a poor outcome in patients with what appears to be a minor stroke,” he says. “On [Fairbanks’] MRI scans, she had a couple of those markers, clearly showing she was at very high risk of worsening in the hospital and potentially being permanently disabled. So this research has allowed us to select the right people for treatment while at the same time not treating people who would be at high risk for complications.”

The Evolution of NINDS

A driving force behind NINDS’ creation in 1950 was Mary Lasker, a health activist and philanthropist who lost both parents to stroke. Lasker lobbied other donors, legislators, and presidents to increase funding for medical research. She pushed Congress to create the institute, initially called the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness, says NINDS director Walter Koroshetz, MD. The institute’s initial budget—$1.24 million—was the first dedicated federal funding for neurologic research in the United States.

Lasker’s influence—she had pressed President John F. Kennedy to create a national commission on cancer, heart disease, and stroke in the early 1960s—also helped lead to NINDS’ expansion and renaming in 1968. (The blindness program split off into the new National Eye Institute.)

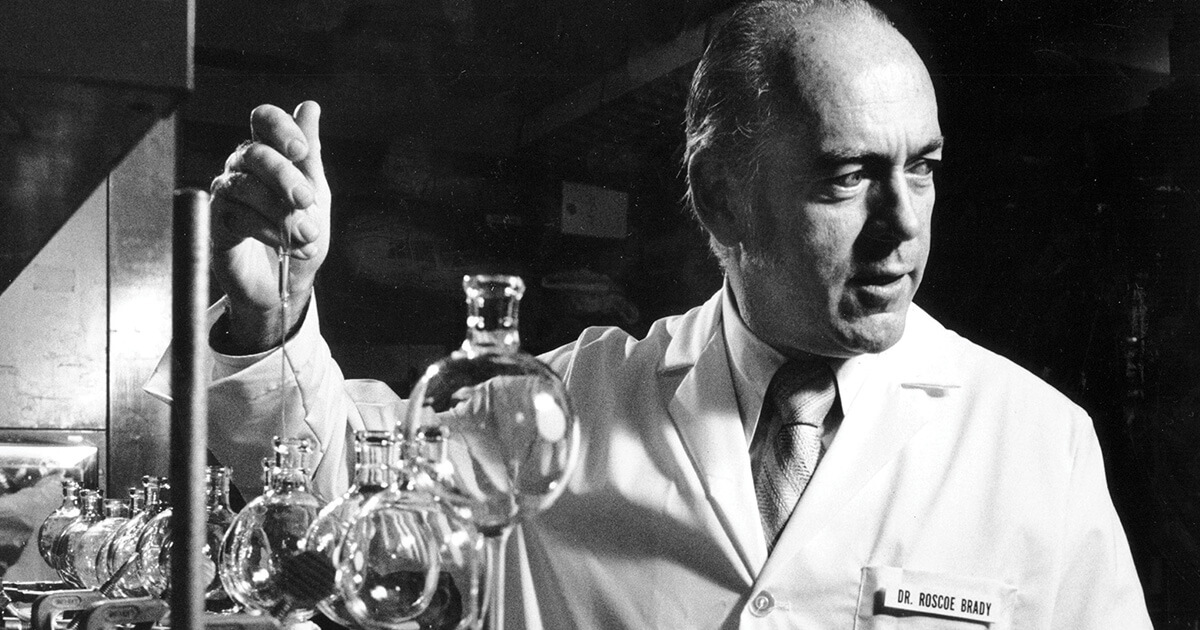

One of NINDS researchers’ first major discoveries came in the early 1960s with the identification of the enzyme deficiencies responsible for several inherited metabolic disorders, including Gaucher and Fabry diseases. Roscoe Brady, MD, who joined NINDS in 1954 and spent his entire career there, did the pioneering work and ultimately headed the developmental and metabolic neurology branch. Over three decades, Dr. Brady and his group essentially created the field of enzyme replacement therapy, which transformed fatal inherited diseases into treatable chronic conditions.

Today, with a budget of just over $2.03 billion, NINDS has two major divisions: intramural research, one of the largest neuroscience research centers in the world, which conducts important research in basic, clinical, and translational neuroscience, and extramural research, which funds programs outside the NIH, including major clinical trials, and supports training for future neurology and neuroscience leaders.

A major component of the agency is StrokeNet, a group of regional stroke centers established in 2013 to promote and conduct high-quality clinical trials focused on advancing acute stroke treatment, prevention, recovery, and rehabilitation. Another is the Network for Excellence in Neuroscience Clinical Trials (NeuroNEXT), established in 2011 to develop and conduct clinical trials of promising new therapies for neurologic disorders other than stroke in partnership with academia, private foundations, and industry. At least 10 NeuroNEXT studies are at various stages of completion, testing biomarkers or therapies for several conditions.

Countless great advances in the treatment of once “untreatable” disorders have come about through the support of NINDS. One remarkable example is spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a group of hereditary diseases causing progressive muscle weakness and degeneration. SMA primarily affects infants and children and occurs in 1 in 10,000 births, making it the second most common severe hereditary disease of that age group (after cystic fibrosis). The most severe and more common form, SMA type 1, until recently, was almost universally fatal by age 2. Work NINDS supported, however, helped identify the gene that causes SMA, known as SMN1, and a nearly identical back-up gene, SMN2, that partially compensates for SMN1 deficiencies.

Between 2003 and 2012, NINDS piloted the Spinal Muscular Atrophy Project to accelerate research and development of new therapies. This ultimately led to the approval of several groundbreaking treatment options: a gene replacement therapy called Zolgensma and two drugs, nusinersen (Spinraza) and risdiplam (Evrysdi). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s 2016 approval of nusinersen marked the first time an antisense oligonucleotide therapy, which alters genetic instructions to produce a healthy version of a missing or damaged protein, was successfully used to treat a neurologic disorder.

Dr. Koroshetz anticipates many more advances in treatments for neurogenetic diseases with the support of NINDS research in the near future. Foundational neuroscience studies have helped lead to today’s gene-editing programs, he says. “I was recently at a meeting with people who are working on programs to gene-edit Huntington’s disease, ataxia, prion disease, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy,” Dr. Koroshetz adds. “These therapies are among the most powerful and precise tools that we will have to treat neurological diseases.”

In May 2025, researchers shared that the gene-editing tool CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) was used to treat an infant with a urea cycle disorder, in which toxic, brain-damaging levels of ammonia build up in the body. It was the first time CRISPR was successfully used to fix a single patient’s unique genetic error.

“It sounds like science fiction, but these things are going to happen, and how fast they happen depend on how much we invest in moving this research forward,” Dr. Koroshetz says. “Thanks to networks like NeuroNext and StrokeNet, as well as our therapy development team, we have been quite effective at getting the process of therapeutic development to fruition.”

NINDS also played an instrumental role in training the next physician-scientists, Dr. Josephson adds. “Generation after generation, these are the people who have made these discoveries and cures reality,” he says. “It’s impossible to overstate how important and successful NINDS has been for people with neurologic conditions and their families. … If we are to continue the remarkable pace of breakthroughs in neurology that we’ve enjoyed in the last two to three decades, continued support for NINDS is essential.”

Fairbanks agrees. “I feel like I walked away from a crazy car accident without a scratch on me,” she says. “All these experts and all this research came together to help me. I’m just so grateful.”

NINDS Through the Years

- 1950: President Harry S. Truman signs Public Law 81-692, establishing the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness.

- 1968: The institute is expanded and renamed the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS).

- 1976: D. Carleton Gajdusek, MD, chief of NINDS’ Laboratory of Central Nervous System Studies, receives a Nobel Prize for work on atypical slow virus infections.

- 1989: President George H.W. Bush signs a resolution declaring the 1990s the “Decade of the Brain.”

- 1991: A team led by Roscoe Brady, MD, develops alglucerase injection (Ceredase), the first approved enzyme replacement therapy for Gaucher disease.

- 1996: Based on NINDS research, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) becomes the first approved treatment for acute ischemic stroke.

- 1997: Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is approved to treat Parkinson’s disease, thanks to critical studies from NINDS neuroscientists. NINDS-funded scientists also advance brain stimulation to control seizures in people with epilepsy.

- 2013: The NeuroBioBank gives researchers access to human brain tissue for studying and driving advances in brain disorder treatments.

- 2014: The John Edward Porter National Neuroscience Research Center, housing intramural researchers from NINDS and other institutes, opens in Bethesda, MD.

- 2014: The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative kicks off, aiming to develop and apply new technologies to answer key questions about the brain.

- 2015: Based on NINDS-funded research, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association update their stroke treatment recommendations to include using stent retriever devices for clot removal in certain emergent or acute stroke cases.

- 2016: The Accelerating Medicines Partnership (AMP) Parkinson’s disease project launches with substantial support from NINDS.

- 2016: NINDS launches the Mind Your Risks campaign to raise awareness about the connections among high blood pressure, stroke, and dementia.

- 2016: The 21st Century Cures Act establishes the Beau Biden Cancer Moonshot and NIH Innovation Projects, providing $1.5 billion for the BRAIN Initiative.

- 2017: The first treatment for Batten disease, a group of rare genetic disorders affecting young children, is approved thanks in part to NINDS research identifying its cause.

- 2018: Results from a NINDS-funded clinical trial expand the window of treatment for emergent or acute stroke.

- 2024: Building on decades of NINDS-funded research, several DBS therapies are announced, including brain-computer interfaces enabling people with paralysis to communicate.