The prevalence of RLS in our sample was found to be 25.4%, significantly higher than the general population prevalence, which typically ranges between 3.9 and 14.3%2.

The prevalence observed aligns with international data; suggesting that psychiatric patients, particularly those with mood and anxiety disorders, are at an increased risk for RLS25. A study by Okan et al. in Turkey showed the same trend with 17.3% prevalence of RLS among their psychiatric outpatient population25. There are some differences in the prevalence rates across studies, with some countries reporting even higher prevalence, particularly in psychiatric inpatient settings. In India, the prevalence of RLS in psychiatric outpatients has been reported as high as 50–67% in patients with depression or anxiety26 while studies in Western populations tend to report lower rates. These discrepancies could reflect variations in diagnostic criteria, population demographics, and differences in lifestyle factors that influence RLS1,2.

While this study is one of the first to investigate RLS in a Lebanese community-based psychiatric sample, prior work from Lebanon reported an 18% RLS prevalence among hospitalized psychiatric patients, underscoring the need for region-specific data19. Dietary patterns common in Lebanon and the broader Middle East, such as lower consumption of bioavailable iron and widespread vitamin D deficiency, may influence both RLS and psychiatric symptomatology27. A study by Wali et al. in Saudi Arabia found a significant association between vitamin D deficiency and RLS27. In the Middle East, vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent; a 2023 Lebanese exome-wide study identified novel genetic loci associated with low vitamin D levels28. These findings indicate both environmental (diet, sunlight exposure) and genetic predispositions that may heighten RLS risk in Lebanese populations28.

Notably, the majority of our RLS patients were previously undiagnosed, or unaware of the condition which underscores the importance of actively screening for this condition in psychiatric settings where it is often overlooked14,15.

Our study found no significant differences in age, sex, or lifestyle factors between those with and without RLS, which suggests that RLS may not be strongly influenced by these typical risk factors in psychiatric population. Our results showed a trend towards higher prevalence of RLS among females (69.7%), although this did reach statistical significance (p = 0.07). Prior research has consistently reported a female predominance in RLS3. Hormonal fluctuations, especially elevated estrogen, progesterone and prolactin, have been implicated as contributing factors, particularly during pregnancy, the menstrual cycle and menopause3,29. Prior studies have also shown reductions in RLS or periodic limb movements with estrogen-progesterone therapy, suggesting their interactive role30. Nevertheless, the lack of statistical significance may reflect limited power due to modest sample size, which underscores the need for larger sex-stratified studies to identify gender-specific and biological determinants of RLS. Furthermore, the average age of RLS patients in our cohort was 28 years which might have interfered with observing a higher prevalence among women possible perimenopause hormonal changes.

The results did not show a significant difference in age between the two cohorts and while age is an established risk factor for RLS with data showing that older patients are more likely to meet the criteria for RLS1,4. The lack of a significance for two RLS risk factors gender and age, suggests that in psychiatric patients, other factors may have greater influence in this population.

Notably, there was a non-significant trend towards a higher frequency of anemia and blood disorders in the RLS group (p = 0.12). Iron deficiency is a well-established contributor to RLS31,32. When Karl-Axel Ekbom first described RLS there was a high prevalence of iron deficiency among patients33. Iron deficiency has been implicated in both the pathophysiology of RLS and some psychiatric disorders, highlighting the need for diagnostic assessments that include iron levels as part of RLS evaluations34. A recent Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis by Trotti et al. showed that iron therapy improves restlessness and RLS severity, which further supports the ground of evidence35.

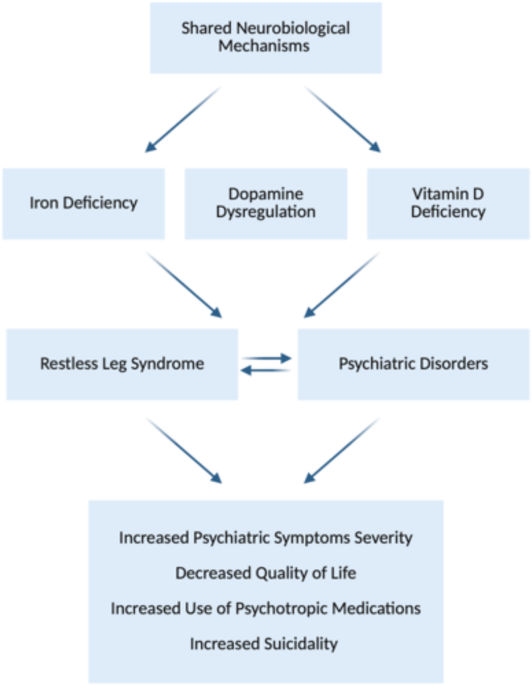

Our results showed a clear association between RLS and psychiatric symptom severity. Patients with RLS scored significantly higher on the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7, indicating more severe depression and anxiety. This finding is consistent with studies reporting a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with RLS36. Given the cross-sectional nature of our study, we cannot determine the directionality of the observed associations between RLS and psychiatric symptoms. It is possible that RLS contributes to depression and anxiety through mechanisms such as chronic sleep disruption, physical discomfort, and impaired quality of life. Conversely, psychiatric distress, particularly in the context of chronic anxiety or depression, may exacerbate RLS symptoms, either directly through psychophysiological mechanisms or indirectly via medications known to influence dopaminergic pathways (Fig. 1)36. Importantly, emerging evidence supports the hypothesis that both conditions may share common neurobiological substrates. Brain iron deficiency is central to RLS pathophysiology; iron acts as a critical cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis. Reduced iron availability impairs dopaminergic signaling in the substantia nigra and other basal ganglia regions involved in both motor control and mood regulation. Dopamine dysfunction has also been implicated in depression, anxiety, and sleep regulation, making it a plausible common pathway36. A 2024 meta-analysis by An et al. confirmed elevated depression and anxiety levels in RLS patients across psychiatric populations36. Similarly, Xiao et al. demonstrated that impaired brain iron trafficking is associated with both RLS symptoms and affective disorders in neuroimaging and genetic studies37. These findings underscore the biological plausibility of a shared mechanistic origin and highlight the need for longitudinal and interventional studies to clarify causality and explore whether targeting iron-dopamine pathways can improve outcomes across both clinical domains.

Conceptual model illustrating the bidirectional relationship between RLS and psychiatric disorders, mediated by shared neurobiological mechanisms.

Our results showed a clear association between RLS and psychiatric symptom severity. Patients with RLS scored significantly higher on the PHQ-9 and the GAD-7, indicating more severe depression and anxiety. This finding is consistent with studies reporting a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with RLS36. RLS severity in our sample was strongly correlated with worse sleep quality as measured by the PSQI, consistent with the established relationship between RLS and poor sleep38. Our data revealed a significant association between RLS and suicidal ideation with RLS patients having markedly higher odds compared to non-RLS patients. This aligns with the findings by Talih et al. who reported that among psychiatric inpatients with suicidal ideation, 21% were found to have RLS (p = 0.01)19. A JAMA study by Zhuang et al. have previously demonstrated an increased risk of suicide and self-harm among RLS patients, independent of lifestyle factors and chronic diseases including depression and sleep disorders39. In other studies RLS patients exhibit increased psychological distress which was associated with suicidality40.

Interestingly, while our study found that RLS patients had significantly poorer sleep, we did not observe statistically significant differences in daytime sleepiness as measured by ESS between the two cohorts after adjusting for potential confounders. This result may be due to the nature of daytime sleepiness, which could be influenced by other factors beyond RLS41. Although RLS is often associated with increased daytime fatigue and sleepiness, our finding suggest that sleep quality, rather than daytime sleepiness, are potentially more relevant for understanding the impact of RLS on somnolence in psychiatric patients.

Our results show a correlation between RLS severity and higher scores on both the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 suggesting a bidirectional relationship between RLS and mood disorders. This correlation has already been established in the literature. One potential explanation is that RLS can exacerbate psychiatric symptoms by disrupting sleep and by causing distressing symptoms, while mood disorders and anxiety and their associated psychotropic medications may worsen RLS symptoms16. Our findings stress the importance of considering RLS as a contributing factor in psychiatric patients with treatment resistant depressive and anxiety symptoms.

We observed that RLS patients in our sample were more likely to be using psychotropic medications and there exists a potential exacerbation of RLS with common psychotropic medications42. Evidence in the literature suggests that while some antidepressants may exacerbate RLS symptoms42. These findings raise the possibility that psychotropic medications may act as confounders in the relationship between RLS and psychiatric symptoms. Many SSRIs and antipsychotics, such as escitalopram, fluoxetine, and quetiapine, have been previously associated with the onset or worsening of RLS symptoms42,43,44. Thus, some of the associations we observed between RLS, and higher PHQ‑9/GAD‑7 scores may partly reflect medication-induced symptom amplification, rather than a direct neurobiological link42. While our study wasn’t powered to parse out causality or dose–response effects, future research should include stratified analyses by medication type and timing, ideally in longitudinal designs, to fully disentangle pharmacologic from disease-related influences.

Limitations

The study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes conclusions about causality. While our findings suggest associations between RLS and psychiatric symptoms and their severity, we cannot determine whether RLS exacerbates depression and anxiety, whether psychiatric distress worsens RLS, or whether both are driven by shared neurobiological mechanisms such as iron deficiency, dopaminergic dysregulation, and vitamin D deficiency. Second, our sample primarily included young patients (mean age ~ 28), which may limit generalizability to older psychiatric populations where RLS is more prevalent as per the literature. Lastly, as the study was conducted in Lebanon, contextual factors such as dietary iron intake, vitamin D deficiency, healthcare access, and chronic socioeconomic stress may have influenced the observed prevalence and symptomatology of RLS.