Immune cell researcher Ying Hu describes his microscopic subjects as ocean liners cruising in a pitch-black sea.

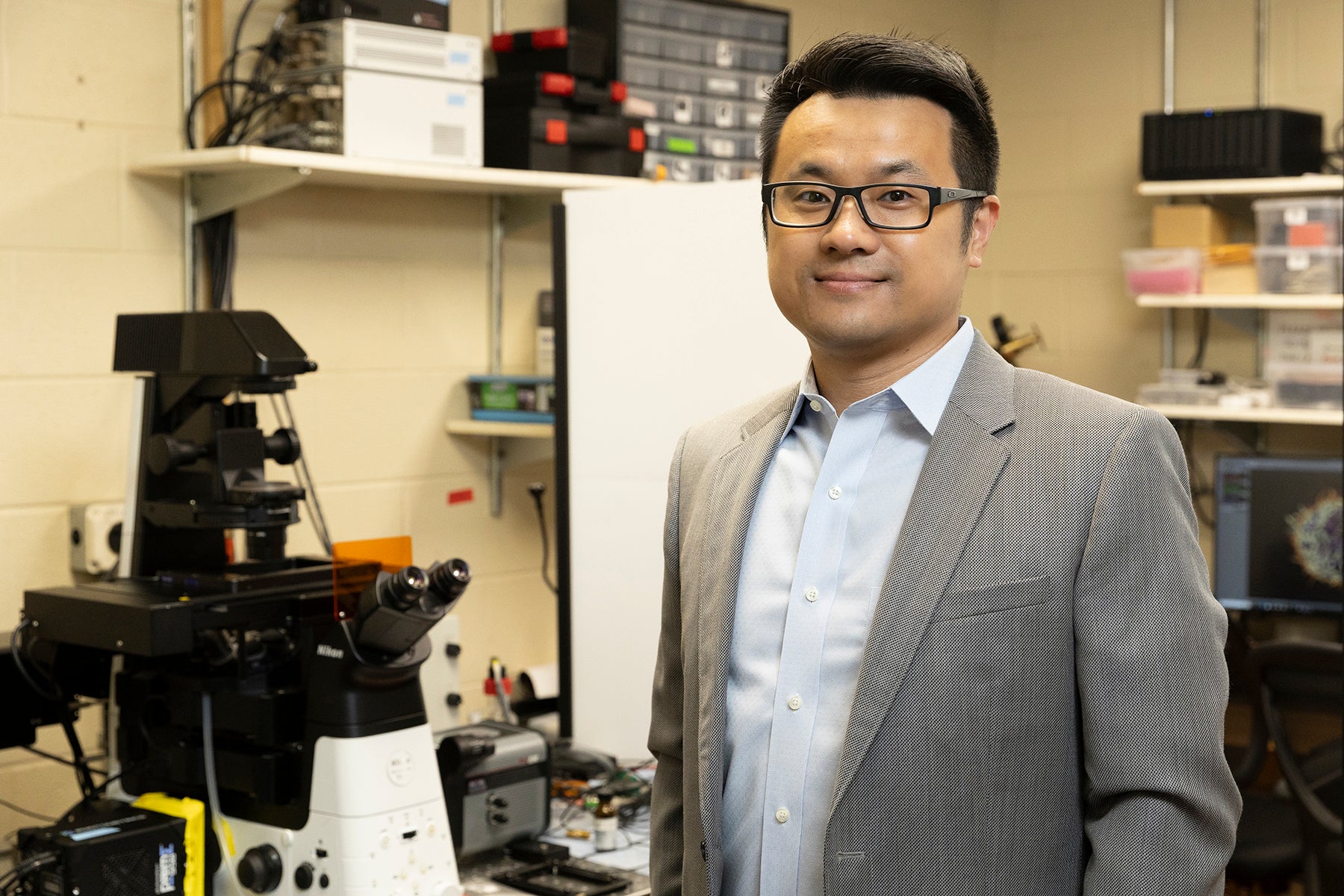

“Imagine a ship with no lights on. You don’t know how big the boat is or what its outline looks like. Similarly, if you don’t know an immune cell’s shape and structure, it’s difficult to visualize because you don’t know what to look for,” said Hu, an associate professor of chemistry in the UIC College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and member of the University of Illinois Cancer Center.

In Hu’s analogy, the ship’s lights are comparable to the proteins in a cell’s outermost layer: the plasma membrane.

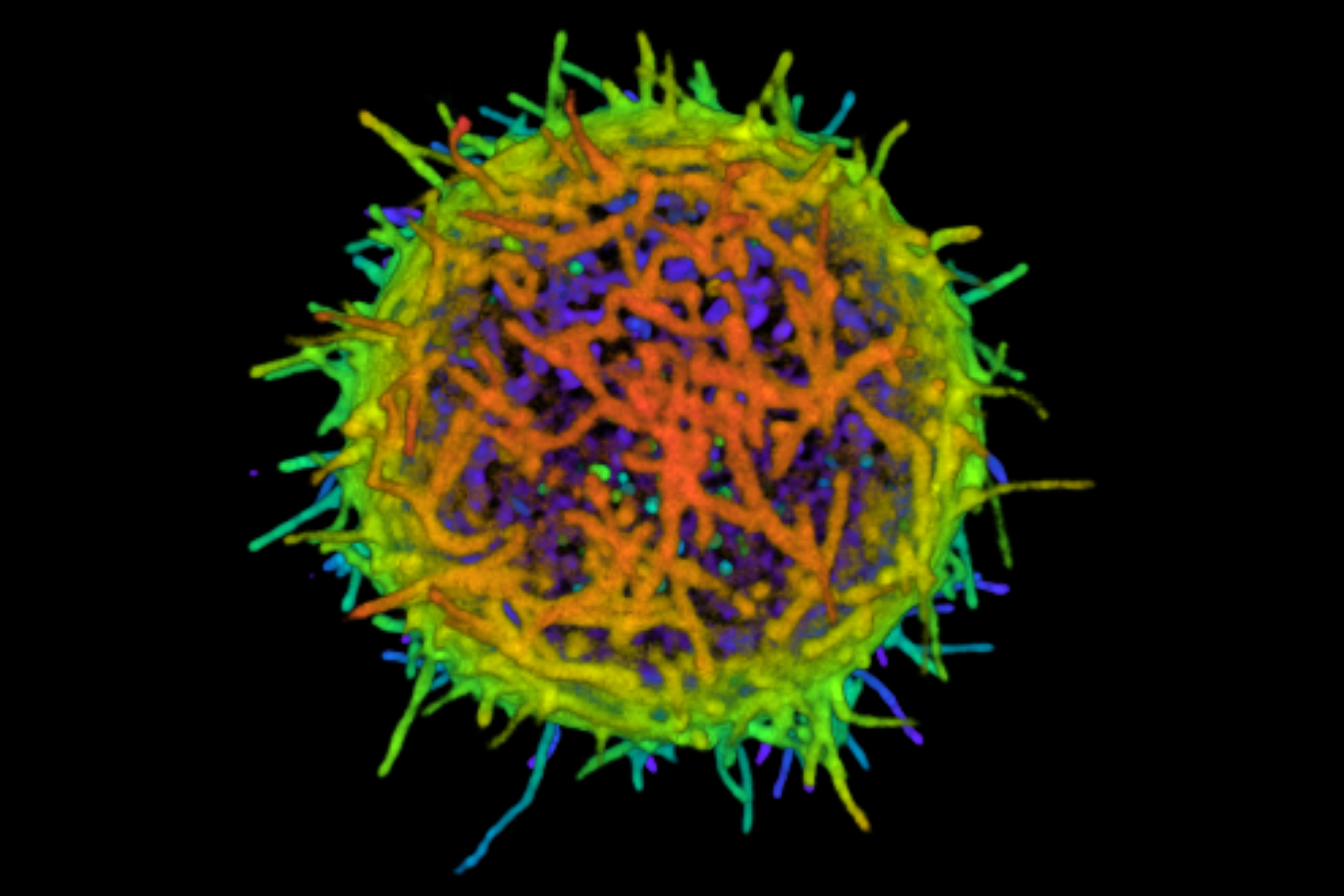

In a Nature Communications study, Hu and colleagues introduced a technique to create a visual of a mammalian immune cell’s plasma membrane structure in less than five minutes. By chemically staining proteins on the cell’s plasma membrane, researchers can map the cell’s structure and better understand how it communicates and fights threats like cancer.

Essentially, the technique “turns on all the ocean liner’s lights at once,” Hu said.

To label proteins, researchers typically track them down and attach a naturally fluorescent protein derived from a bioluminescent jellyfish. The catch? Researchers must know the protein’s identity to track it down. Hu’s method, which uses chemistry to light up all proteins indiscriminately, catches 90% of the proteins in a cell’s outer layer — even those that haven’t already been found.

Visualizing a cell’s plasma membrane provides insight into its functions: facilitating cell-to-cell communication and fighting harmful agents like viruses, bacteria and cancer. Understanding immune cells also helps patients choose the best treatment, Hu said.

“Immunotherapy, where a patient’s immune cells are mutated to fight cancer, is a miracle, but it doesn’t work for everyone,” he said. “With our method, we could conduct a ‘check-up’ on patients’ T-cells to see if immunotherapy is a sustainable choice.”

Hirushi Gunasekara, a postdoctoral researcher in chemistry and the paper’s first author, said that visualizing immune cells and other cells is key to unlocking many of nature’s mysteries.

“We’re repurposing a robust, classical chemistry reaction for a broader application,” she said. “Anyone can use this, even people who are not trained in chemistry, to help understand and fight cancer and other immune threats.”

Additional UIC authors include: Yu-Shiuan Cheng, Vanessa Perez-Silos, Alejandro Zevallos-Morales, Daniel Abegg, Alyssa Burgess, Liang-Wei Gong, Richard Minshall, Alexander Adibekian, Carlos Murga-Zamalloa and Alison Ondrus.

Research reported in this press release was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R35GM146786. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.