The main findings of this study show that intoxication and suicide threats/attempts are the most common symptoms of patients in the EMS with mental illness. Moreover, one-fifth of those assessed by EMS clinicians were hospitalised. Overall, this seems to be a difficult patient group to triage under the current triage system since four out of ten patients were not assigned a triage colour.

Previous research conducted in Asia [16] and Scotland [15] has shown that patients who are intoxicated with alcohol and/or drugs are common in the EMS. This was likewise evident in the present study. Holzer and Minder [24] gathered data over ten years, looking at patients who had intoxication as the primary reason for assessment in the EMS, and they found an increase over time by approximately 5% per year. In the present study, patients who were intoxicated stood for the highest number of hospitalisations, although the number is low in relation to the summation of patients assessed due to intoxication. Smith-Bernardin, Kennel and Yeh [25] conducted a study on patients who were intoxicated by alcohol and examined whether the emergency department is the right referral for these patients. They found the sobering centre as a safe alternative to the patients being referred to emergency departments. In Sweden though, sobering centres exist in only six regions but is something being discussed at the government level due to the increasing number of intoxications [26]. In an interview study, patients who use the EMS when intoxicated expressed guilt over using ambulance resources but at the same time, most patients reported an unwillingness to change their alcohol misuse and depend on external support, leading to the continued frequent use of the EMS service [16]. These contradictions of feeling guilty but not accepting care could be explained by the shame and feeling of being judged for alcohol misuse that patients express [27]. One might assume that the suffering these patients experience is due to this conflict of interest. The question remains, however, whether the emergency department is the right level of care for these patients, as being transported to and being in, the emergency department could cause additional stress for the patient. On the other hand, you could assume that it at the same time brings relief as the patients get access to care quickly, which could increase the patient’s sense of safety.

Another finding that stood out in the present study was suicide threats/attempts, with suicide threats being the most common initial assessment by dispatchers. Worldwide, more than 720,000 people die every year from suicide, and for every suicide, there are many previous threats and attempts [28]. In Sweden, 1617 people were either confirmed to have committed suicide (82%) or suspected of doing so (18%) in 2023 [29]. It is therefore unsurprising that EMS clinicians meet these patients often, something supported by previous research [30, 31]. In many cases, the suicide threats/attempts are in combination with intoxication in intentional ways to try to commit suicide [30, 31]. However, in the present study, not one patient got suicide as an ICD 10 code assigned after EMS assessment, although we can conclude that these patients got “F99 Mental Disorder” as the diagnosis code, as the number is consistent with the number of patients assessed initially due to suicide threat/attempt. These patients did not tend to be admitted to the hospital, based on the findings that none of the patients got suicide ideation or suicide attempt as an ICD 10 code when admitted, which is concerning since, as stated earlier, for every suicide, there are several threats and attempts [28]. Research [32] has also shown that the feeling of hopelessness may be a contributing factor to repeated suicide attempts, which can be interpreted as a desire to be seen and get help, rather than a desire to die. One might assume the suffering these patients experience when calling for help and not receiving care. Patients who called for the EMS while being in a suicidal process describe in an interview study the suffering they are in, in such a vulnerable place, feeling suicidal, and at the same time they struggle with the stigma and fear of being judged [33]. Drawing the conclusion they were coded with “F99 Mental Disorder” and were referred to the emergency department but then not admitted makes you wonder where these patients should receive care, for their suicidal ideation, that is sustainable in the long run, to avoid trips to the emergency departments.

In line with this, neither intoxication nor suicide threats/attempts seems to be sufficient to allow admission to the hospital, where the present study shows that only one-fifth of the patients referred to the emergency department were admitted to the hospital. However, it is important to clarify that in the present study, we do not know if the patients wanted to be hospitalised. For example, patients who were in a suicidal process described that the most important thing for them was to be seen, heard, and acknowledged as human beings in their suffering and receive validation of their feelings [33]. It still raises the question of whether the emergency department was the right place for referral or where these patients should be referred to have their care needs met. In the present study, approximately 30% of the patients got either Red or Orange as a triage colour, indicating the need for acute care. The other patients got a lower triage colour, indicating there was no need for acute care. Previous research shows that many patients with mental health problems have sought care in primary care but did not receive help for their illness, leading the patients to call for an ambulance [13, 14]. Patients with mental illness describe how important it is to be acknowledged as a person and receive care for their mental illness. When being dismissed, this could increase the suffering [18]. One might assume the helplessness and suffering these patients feel, not receiving the care they need or being admitted anywhere [hospital, primary care]. However, in the present study, the EMS clinicians only referred the patients to primary care in 3% of the cases as most patients were transported to the emergency department. This could be because of a lack of competence and confidence in the EMS clinicians when assessing patients with mental health problems [10, 11], leading the EMS clinicians to play it safe and take the patient to the emergency room for instant care, instead of referring to primary care [34]. It could also be due to the lack of decision support and guidelines regarding where to refer the patient, leaving it up to the EMS clinician to go with their gut feeling and intuition [11]. These factors in combination could be the cause of why patients are referred to the emergency department when there is not always a need for acute care [35]. Another suggestion for why EMS clinicians refer patients to the emergency department when acute care is not always needed is the desire to help these patients as EMS clinicians witness their difficulty with mental health problems and receiving help from primary care and therefore drive the patient to the emergency department in the hope of helping them get the ball rolling [11]. On the other hand, another reason why patients are not referred to the emergency department, as outlined in the previous study, could be because of the difficulty in triaging patients with mental health problems as the current triage system WEST [21] is mainly focused on physical health problems, not mental health problems. The fact that there are no indications for the different triage colours within mental health problems; rather, it states that there are no individual warning signs for mental illness and that the EMS clinicians need to make their own assessment based on the clinical assessment, with special consideration for suicidal thoughts, psychotic symptoms, and aggressivity. This could be why 40% of the patients in the previous study were missing a triage colour or, referred to the emergency department, and then were not admitted; in other words, there is a lack of decision support and guidelines making it hard to assess the patient’s to the right level of care.

Patients with mental illness are already struggling with stigmatisation in society and describe how they felt ashamed when calling for an ambulance due to mental health problems as they were afraid of not being taken seriously [27]. At the same time, the present study, strengthened by several other studies [13, 14, 17, 35] suggests that the EMS and emergency department are not the right place for these patients. The question remaining is how these patients should receive care and where the EMS clinicians should refer them to alleviate their suffering. This needs to be addressed in future research.

Method discussion

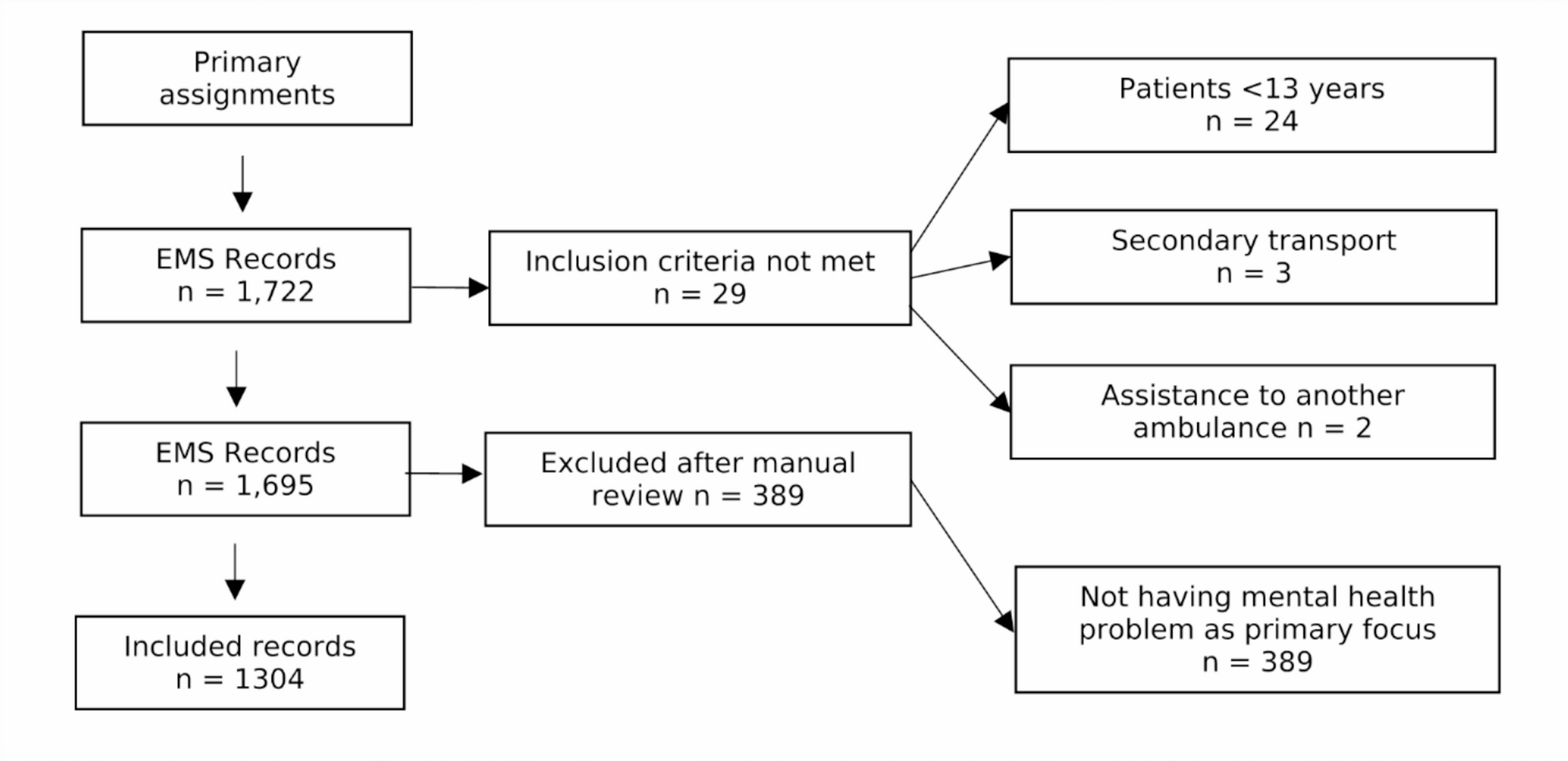

When extracting the data from EMS records, one inclusion criterion was that the patients had to be over 13 years old. This age was determined by the fact that, in Sweden, health services consider patients at the age of 13 to be cognitively developed enough to start taking responsibility for care contacts; thus parents have limited access to their medical records. We believe this cognitive development also reflects on their actions and feelings when it comes to mental illness, making over 13 years an age at which we could identify as many patients as possible in as wide an age range as possible.

During the manual review, 389 patients were excluded for not having mental health problems as the primary focus. These patients were included in the original dataset because they met the inclusion criteria. However, upon manual review, it was found that a patient could have, for example, called an ambulance for a fracture and had a mental illness in their medical history. However, as mental illness had nothing to do with the assessment, they were excluded.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study was a large database of 1300 patients assessed specifically for mental illness. It provides a diversity to the data which increases generalisability and reliability. However, a limitation was that mental illness can disguise itself as physical illness. This means there may be an underreporting in the actual statistics of those assessed by the EMS for mental illness, as data were retrieved from specific variables that were directly related to mental illness.