This is the first study to use a random sample to look into the prevalence of MLTC in patients with lymphatic filariasis. We observed hypertension to be the most common comorbid chronic condition, followed by peptic ulcer disease, visual impairment, arthritis, and diabetes, which is in contrast with the findings of another study conducted among 323 tuberculosis patients in two states of India that reported depression to be the most prevalent condition, followed by diabetes, peptic ulcer disease, and hypertension [29]. Nonetheless, hypertension, diabetes, and peptic ulcer disease had the highest prevalence across both studies that looked at the interface of chronic infectious disease with non-communicable diseases. A probable reason for this could be that patients with lymphatic filariasis share the exposure to the drivers of NCDs in India. Moreover, a few studies also highlight that lymphatic filariasis patients have chronic inflammation due to lymphedema and elephantiasis, which may contribute to the development of cardiometabolic diseases, as proinflammatory immune responses increase the onset of these conditions [30]. Additionally, arthritis attributable to Wuchereria bancrofti has been reported among Indian patients, and its pathogenesis is linked to immune complex deposition or inflammation due to the presence of adult worms in the joint space [31].

The prevalence of MLTC in our study was greater than that reported in a study conducted in two states of India i.e. Telangana and Odisha, in which the prevalence of multimorbidity among tuberculosis patients was approximately 52% [29]. Additionally, a study conducted among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients reported that the prevalence of multimorbidity was approximately 48% [32]. Nonetheless, the prevalence of MLTC among lymphatic filariasis patients is greater than the global pooled prevalence of multimorbidity, which is approximately 37%, as reported by a recent systematic review based on 126 peer-reviewed studies [33].However, it is worth noting that that the mean age of participants in our study was around 62.1 years which may be one of the reasons for higher prevalence of MLTCs in this study. However, this highlights the need for the assessment of MLTCs among lymphatic filariasis patients to design evidence-based policies in the future to provide continuity of care for these individuals.

The chances of having MLTC increased with increasing age, which is consistent with the findings of a systematic review that identified older age to be a risk factor for multimorbidity [34], while another systematic review conducted with the aim of identifying risk factors for multimorbidity also showed that increased age was positively associated with multimorbidity [35]. A study conducted in Delhi, India also reported that multimorbidity increased with age, which is in agreement with the findings of our study [36]. This finding highlights two major areas to be focused upon, the first being the demographic shift, which will lead to the addition of an aging population who will require healthcare services. Second, India is attempting to eliminate lymphatic filariasis by 2027 (three years ahead of the global target), which means that further transmission will be interrupted with no new cases [10]. However, patients with existing lymphatic filariasis can survive for many years. Additionally, the burden of MLTC, as indicated by the present study, is high in this group; hence, these individuals will require quality healthcare facilities, thus warranting the strengthening of primary care.

In our study, males were identified to be at a greater risk of having MLTC than their female counterparts, which is incongruous with the existing MLTC literature in India [21, 22, 36]. All studies to date have reported that females are at greater risk of having MLTC, whereas the present study showed that males are at greater risk of having MLTC, which is a novel finding. A probable reason for this could be the gender roles assigned by society in India and other similar cultures. Despite having lymphatic filariasis, females perform household chores that involve physical activity, whereas males will rest if they are diagnosed with a disease leading to reduced physical activity, increased obesity and other risk factors for developing MLTC.

We observed that participants with more years of schooling had a greater chance of having MLTC, which is consistent with the findings of a systematic review that also revealed higher education to be directly associated with multimorbidity in Southeast Asia [37]. A probable reason for this could be that with education, people tend to be more health conscious and hence have better chances of being diagnosed and self-reported with chronic conditions. Nonetheless, this finding implies that health literacy should be provided to people with no formal education or fewer years of education.

We observed that participants who did not work were at a greater risk of having MLTC, which is consistent with the findings of a systematic review that reported that not working or being unemployed increased the risk of having multimorbidity, particularly substance use patterns [38]. Moreover, studies have reported that socioeconomic marginalization increases the risk of multimorbidity, which stands true for patients with lymphatic filariasis, as this disease mostly affects the poorest people of the poor population and often leads to disability, contributing to a loss of livelihood opportunities [20,21,22, 39]. Hence, it is crucial to identify the care-seeking pathways of these patients to make the existing programmes more equitable.

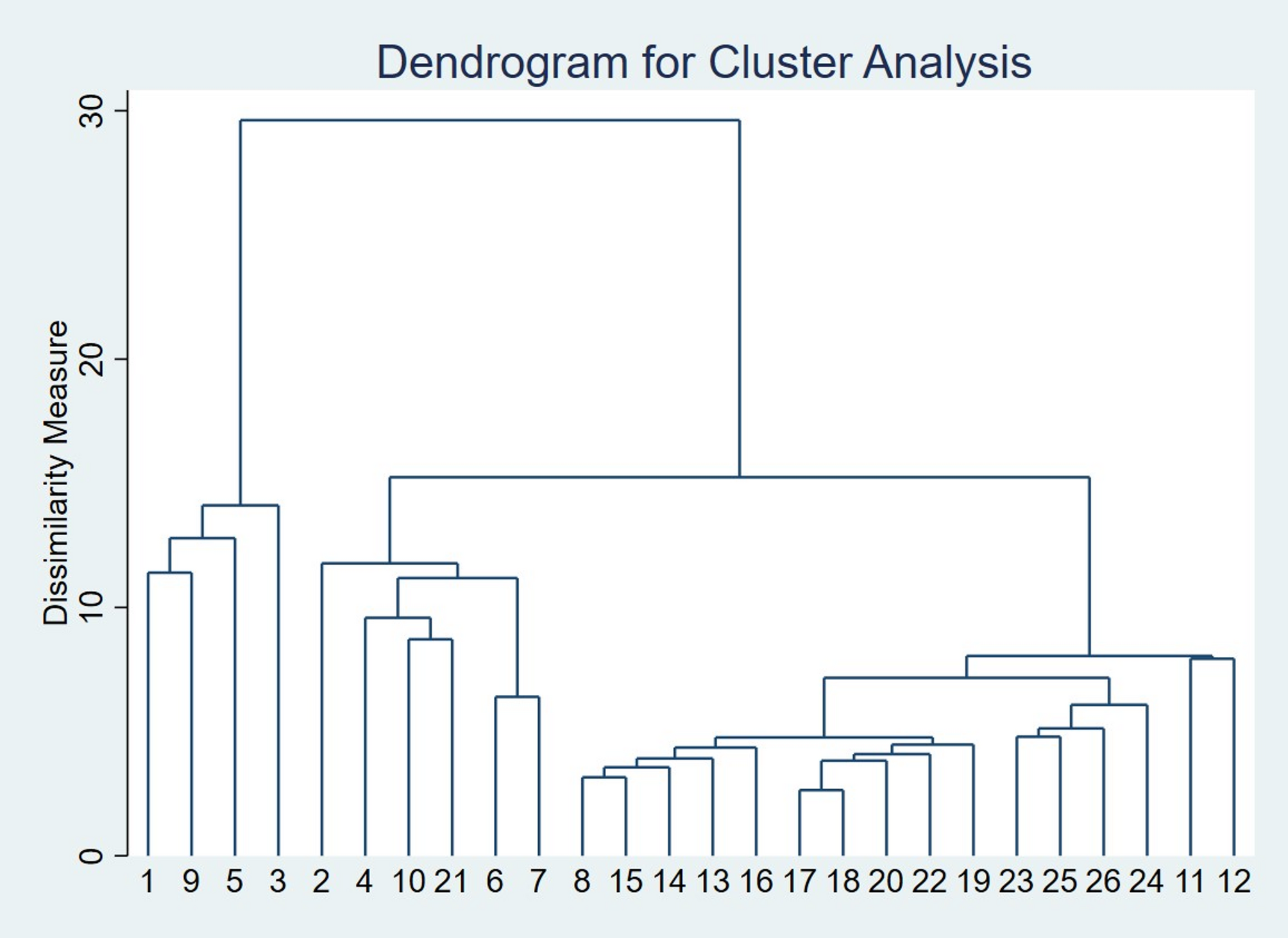

The most commonly occurring pattern among patients with lymphatic filariasis was hypertension and diabetes, which is congruent with the findings of a systematic review that reported that cardiovascular and metabolic diseases were the most commonly observed multimorbidity patterns in Asia [40]. Our findings also align with the findings of another systematic review showing hypertensive diseases were the most frequent condition in all dyads, followed by gastrointestinal conditions, arthropathies and diabetes mellitus, in India and China [41].

There was a per unit decrease in self-rated health with an increase in the number of chronic conditions, which is in agreement with the findings of a systematic review that reported a mean decrease of -1.5% to -4.4% (varied depending on the scale used) in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) per added disease [42]. Notably, poor quality of life among our study population was a cumulative effect of MLTC, along with existing disability and functional decline due to chronic lymphatic filariasis, which needs to be addressed.

Implications for policy and practice

The findings suggest MLTC to be common among lymphatic filariasis patients, which calls for linking these patients to their nearest Ayushman Arogya Mandir (AAM) or primary healthcare centers formerly known as Health and Wellness Centers for continuity of care. AAMs are established with a vision to strengthen primary care by providing preventive and curative services in the patient’s vicinity with an expanded range of services, especially those curated for chronic conditions. However, lymphatic filariasis is not included in this list despite being prevalent in 339 out of 766 districts across 20 states and Union Territories of India. Hence, the states should be directed to add locally important diseases to the list of AAMs, as health is a state subject in India. This will help in providing quality care to these patients who would eventually help in achieving universal health coverage.

Individuals with lymphatic filariasis, as seen in our study, mostly belong to deprived strata of society and hence need additional support, which may cause them to incur out-of-pocket expenditures and the risk of impoverishment during treatment. Hence, MLTC among these patients is far more challenging and requires additional efforts to combat. Here, patient-centered holistic care for all ailments at one point/facility is of utmost importance as multiple (self-) referrals to a variety of specialists is not realistic due to disability and low socio-economic status.

Community health workers (newly recruited cadre of trained nurses) can play a major role in keeping track of these patients by regularly screening for common chronic conditions and managing multiple morbidities through periodical investigations, motivating regular physician visits and helping them in procurement as well as taking their medications. This could be brought under the ambit of the existing Morbidity Management and Disability Prevention (MMDP) component of the Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination Programme by further increasing its scope. Moreover, diabetes (via polyneuropathy) and hypertensive disease (via heart failure ) might aggravate disability of lower extremities in LF patients making effective control of these co-morbidities essential for long term success of LF care.

Additionally, there is a need for family-based approaches for reducing shared risk factors for MLTCthat may require behavioral change interventions. Future studies should develop interventions to manage MLTC in this population. Addressing disparities in accessing healthcare and improving access to integrated healthcare services at a single platform may help in mitigating the burden of multiple chronic conditions among lymphatic filariasis patients [43].

Strengths and limitations

This novel study has a number of strengths, including the use of a random sample, the assessment of common MLTCs, a high response rate, and associations with a number of risk factors, but it was conducted in only one state of India. We used a pre-validated tool to assess MLTC, which was also one of the strengths of this study, but our data were limited by self-reported chronic conditions that may have resulted in recall bias. Nonetheless, we triangulated the self-reported data with those of community healthcare workers. We did not include phenotypic measurements, which was another limitation of the study. Additionally, we could not establish causality, as our study was cross-sectional in nature.