This study provided the most recent population-based estimates of the malaria burden in the second-most populated province of Pakistan. Malaria incidence of 92 per 1,000 people per annum was estimated at primary health care facilities. This is one of the highest beyond the African region. Cumulative estimates of 16.7 million suspected cases occurred during a 13-year period in the province of Sindh, about 1.28 million cases annually. Significant heterogeneity in malaria burden was observed across districts. Six districts, namely Khairpur, Sanghar, Naushero Feroze, Badin, Mirpurkhas, and Larkana accounted for over 53% of the malaria burden in Sindh. A distinct seasonal pattern was evident, with peaks aligning with the wet season and post-monsoon period. Since the 2022 floods in Sindh, malaria incidence has more than doubled and continues to persist in the province. The estimates are based on monthly reported suspected cases over 13 years from 1088 primary healthcare facilities. The large malaria datasets encompass 23 districts and 31.8 million population over 13 years. This study provided insight in subnational analysis of malaria for decision-making, in particular district-level estimates for strategic malaria control in the province.

Comparatively, the global report of malaria (2021) estimated 4.8 to 6.4 million annual cases, both suspected (presumed) and confirmed in Pakistan in the last decade (2010–2021) [2]. This study estimated the incidence of suspected malaria cases of 1.28 million annually in approximately 15% of the population of Pakistan, living in 23 districts of the province of Sindh. If extrapolated to entire Pakistan, approximately 8 million malaria cases (both presumed and confirmed) may be occurring annually in Pakistan. Furthermore, due to floods, the rates of malaria have doubled between 2022 and 2024, increasing the incidence.

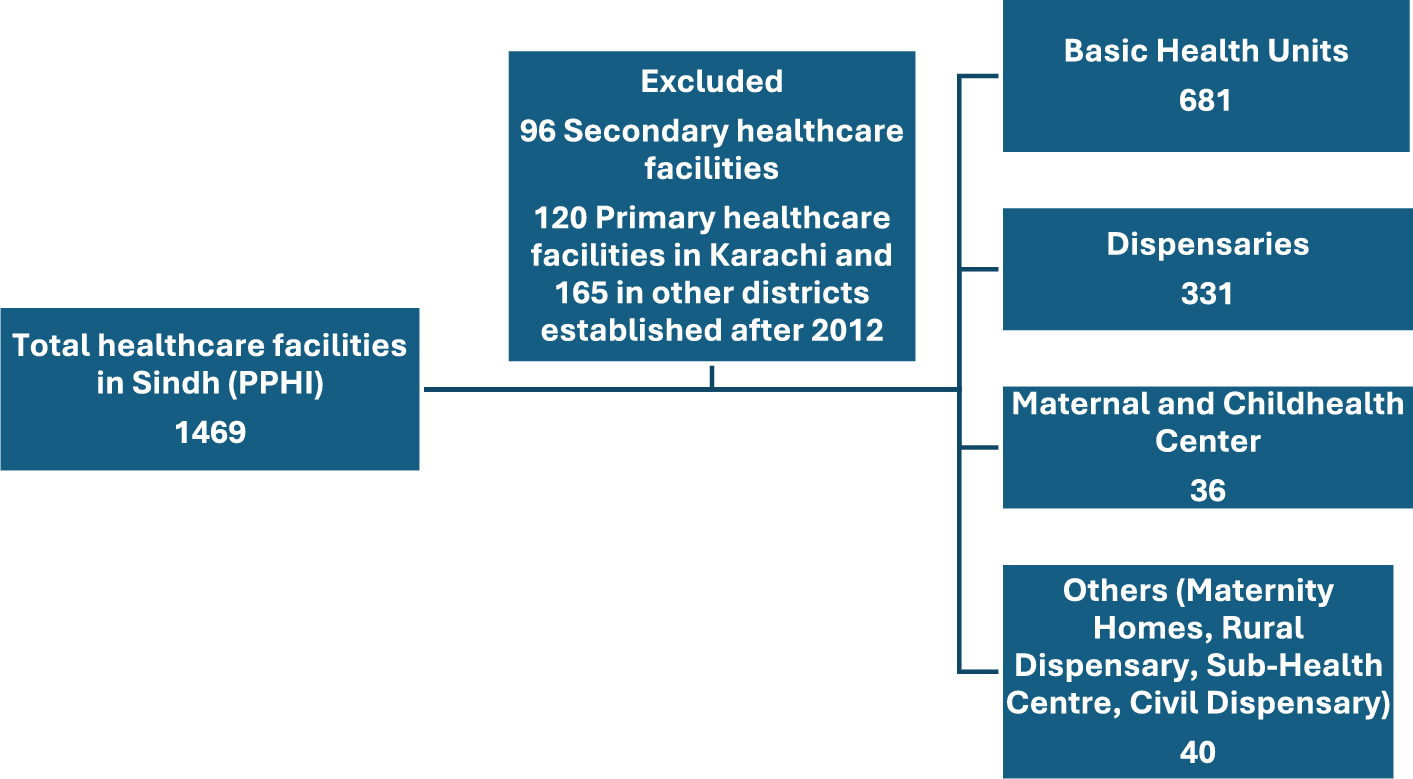

The current study estimated the incidence of 92 suspected malaria cases per one 1000 population per year, and the range observed across districts between 43 and 144 cases per 1,000 people in primary public sector healthcare facilities alone (Table 1). It is important to note that in Pakistan about 60–70% of the population use the private health sector [15], therefore the above tally is an underestimate. Considering that at least three times the cases are seeking healthcare from private health sector, the incidence rate might go above 200 per 1000 per annum and the overall incidence may cross 20 million cases of malaria annually. Furthermore, the study did not include secondary and tertiary care hospitals in these districts which may further underestimate the overall burden. The global malaria report estimated the burden of malaria on the varied quality of data. In areas with limited surveillance data, sub-Saharan African and low-income countries, malaria case estimates are generated using modelled parasite prevalence and geographic information. In contrast, countries with robust surveillance systems can directly use reported case data, adjusted for factors such as healthcare-seeking behaviour and population coverage. Population-weighted estimates derived from actual data are considered more dependable than model-based estimates reliant on weaker surveillance systems. This study utilized data from over 1088 healthcare facilities collected over 13 years, representing a previously unprecedented dataset for Pakistan.

The slide positivity ratio was not obtained from DHIS data, as these records are not captured within the system. However, separate records of slide positivity ratio were consulted. Due to several factors, including non-availability and maldistribution of RDT kits, slide positivity data were not available from all health facilities. Therefore, the malaria positivity ratio was calculated from the limited available data, with an overall positivity of 12.3%, ranging from 7 to 18% across different seasons. Moreover, studies from Pakistan estimated that 15–25% of suspected malaria patients have confirmed malaria [16, 17]. Global malaria reported that the percentage of confirmed cases among suspected patients ranged between 18.1% and 49.7%. Therefore, based on the above estimates of 92 suspected cases, the incidence of confirmed malaria cases in Sindh Province was assumed to range between 11 and 18 cases per 1000 population per year, representing those reported to public healthcare facilities alone. When accounting for cases potentially reported to private sector health facilities, the estimated incidence increases to approximately 30–50 confirmed cases per 1000 population per year. It seems that 1 in 5 presumed cases are diagnosed as confirmed cases of malaria.

The study strength is to provide malaria estimates based on actual incidence from over 1088 health facilities for more than a decade. The method employed by the World Malaria Report relies on adjustments to reported malaria cases based on reporting completeness, test positivity rates, and health service utilization, incorporating household survey data to estimate overall malaria incidence [1]. While this approach allows for standardized cross-country comparisons, it has several limitations for subnational or regional estimation of malaria. It assumes that health service use among children under five represents all age groups, which may not always be valid. The health service utilization rates among children under five are higher than adults. Secondly, the health service utilization is not optimal for any age group because a substantial healthcare cost (direct or indirect) is borne out-of-pocket even if healthcare services are provided free of cost. This assumption may lead to under- or over-estimation of malaria burden in a given country or region. Additionally, the adjustments rely on estimated parameters rather than actual incidence data. In contrast, this approach utilizes direct, monthly malaria incidence data weighted with current population estimates. This method provides a more granular, time-resolved, and empirically driven assessment of malaria trends, minimizing reliance on assumptions about service utilization and test positivity.

This longitudinal analysis also sheds light on the relationship between climate change, malaria transmission, control efforts, and their effects on health services. The 2010 and 2022 floods had a major impact on the incidence of malaria. These events not only led to an immediate increase in malaria incidence during the same year, as reported in previous studies [18, 19], but the data also indicate that the impact persisted for a longer term (three years or more) following the flood events. This suggests that disasters such as floods can disrupt health services for extended periods and undermine years of malaria control efforts. With the increasing frequency of floods, this poses one of the greatest challenges for malaria control in endemic countries.

The study also revealed that the average coverage of the population by public sector healthcare facilities was 46% in the province of Sindh, ranging between 17 and 79% across 23 districts (Table 1). There was moderate correlation between the number of healthcare facilities and total population per district (correlation coefficient: 0.68) suggesting that the distribution of health facilities according to population size can be enhanced to improve coverage. However, given the meagre resources for the health sector, it provides a good population representation of health facilities for primary healthcare across districts in the province [20].

There is a large disparity in the malaria burden in the province. The study highlights six high-burden districts where targeted intervention can be organized to control malaria in the province of Sindh. This also highlights the high disparity between districts based on population-weighted estimates. Spatial distribution identifies the River Indus as a risk factor for malaria. The districts closer to the river have one of the highest burdens of malaria in the province targeted for intervention, as seen in previous studies [21, 22].

The study provided a trend of suspected malaria cases according to seasons (monthly) and spatial distribution across districts, identifying high-burden districts/hotspots. Malaria has a clear seasonal pattern, and two peaks were consistently visible: one in March and the other is a higher peak post-monsoon. The wet season witnessed a surge in cases, while drier months experienced a significant decline. This trend can be attributed to the ideal breeding conditions for mosquitoes, the primary vectors, transmitting malaria during periods of high rainfall and humidity. These peaks highlight the periods when factors such as rainfall and humidity create an environment conducive to amplified malaria transmission [23,24,25]. It is important to note that suspected cases were used to assess the seasonality trend of malaria. However, results are consistent with other studies and robust in indicating malaria seasonality. Two distinct peaks provide critical information for decision-makers to organize control strategies in advance of such surges, which may include targeted distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets and implementation of chemoprophylaxis. This strong seasonal pattern underscores the importance of incorporating seasonal malaria chemoprophylaxis campaigns as part of malaria control strategies in Sindh province. These campaigns involve the targeted administration of antimalarial medication during peak transmission periods, which can significantly reduce the malaria burden [26]. Additionally, the presence of water around the riverbanks during periods of overflow and its stagnancy in bordering areas contribute to the high burden of malaria in these areas. Addressing such factors could be crucial in implementing effective malaria control measures and reducing the disease burden in these regions. Although a significant contributing factor to the high caseload in these locations is stagnant water, the province’s green belts also serve as breeding grounds for mosquitoes [27, 28].

Furthermore, one of the implications of this study is that it has identified high malaria burden districts with low health facility coverage for targeted interventions. Identified districts with targeted interventions would improve efficiency in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of malaria. The population at risk of malaria in Pakistan is not well defined. The funding agencies, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria started to support the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) in 2007, and would find this information useful for allocation efficiency.