In recent years, the evaluation of CRC in the younger population has increased, challenging the previous notion that this disease primarily impacts older individuals [30]. This pattern emphasizes the need to revise screening guidelines to encompass younger age groups for early disease prevention and to decrease the occurrence of complex and costly advanced diagnoses [31,32,33]. Despite potential debates on the cost-effectiveness of limiting screening guideline expansions, research has shown that the overall advantages of reductions far surpass any associated healthcare expenditures in the long run [34, 35]. Timely detection not only saves lives but also minimizes expenses by reducing the necessity for extended treatments and hospitalizations in advanced CRC stages [36].

Our findings indicate a significant enhancement in colonoscopy utilization among individuals aged 55 and above compared to those in the 45–49 and 50–55 age groups. Nonetheless, there has been a noticeable increase in colonoscopy rates within the 45–49 age group over the past years, particularly evident in 2021 and 2022. Additionally, our study shows a strong link between age and polyp incidence, with individuals over 55 consistently displaying the highest polyp numbers. These results underscore the importance of regular colonoscopies, particularly for individuals aged 55 and older, in facilitating early polyp detection and management, ultimately aiding in the prevention of CRC and prompt diagnosis. Moreover, our research illustrates age-related variations in the detection rates of colorectal abnormalities, with individuals over 55 exhibiting the highest polyp detection rate. Interestingly, no notable alterations were observed in the incidence of carcinoma cases between the 45–49 and 50–55 age groups. Over time, ADR reports have been increasing in the population of patients aged 50 years and older, a pattern that corresponds with the existing screening guidelines [37]. Nevertheless, recent epidemiological patterns have exposed a concerning surge in the prevalence of CRC among individuals in a younger age range [38]. This shift has prompted certain scientific bodies in the USA and other regions to support for earlier screening, especially for high-risk individuals or those with a family history of CRC or advanced adenomas [39, 40]. Our study confirms a significant rise in ADR among individuals over 50 years old, aligning with findings from studies conducted in the United States and China. These findings help address objections raised to initiating CRC screening at age 45 [24, 39, 40]. Based on these advancements, predictive analyses, such as the one carried out by Anderson JC. et al., have proposed commencing colonoscopy screening at 45 years, a recommendation adopted by the American Cancer Society [41]. Recent U.S. cohort studies, particularly those by Shaukat et al. [24, 42], provide robust evidence supporting earlier screening [24, 42]. Shaukat et al. [42] demonstrated a significant reduction in colorectal cancer mortality following colonoscopy screening, while Shaukat et al. [24] reinforced the rationale for initiating screening at 45 years, which directly influenced updated U.S. guidelines [24, 42]. While some American institutions have adopted this proposal, other guidelines, including those in Europe, recommend starting screening at the age of 50 [43, 44].

The absence of evidence from studies conducted on a population scale offers insufficient justification for recommending earlier colonoscopies, implying that this approach may only be appropriate in regions where there is a steady increase in CRC cases at a younger age [45, 46]. Various issues have been raised concerning this tactic, such as the broad confidence intervals surrounding the rise in CRC incidence among younger individuals, the arbitrary selection of the 45 to 50 age bracket, uncertainties about the effectiveness rate utilized in predictive models for evaluating cost-effectiveness, projected cost increases in CRC screening, and potential obstacles linked to patient and healthcare provider adherence [41, 47]. Nonetheless, acknowledging that detecting and treating adenomas is a successful means of preventing CRC development, we propose that examining ADR within different age groups can aid in accurately identifying when the risk of colon cancer escalates [14]. Notably, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data showe a comparable number of years of life lost due to CRC between the ages of 45 and 50, and between 50 and 54, as indicated in the study by Syed et al., which noted that a majority of early-stage CRC instances arise in the 40–49 age group [48]. Nonetheless, there is a paucity of studies investigating the connection between adverse effects and age. In a study from 2015, Hemmasi et al. compared patients aged 40 to 49 with those aged 50 to 59 in a limited sample of 740 screening colonoscopies, finding no significant variance between the two groups (11.7% vs. 16.5%), which suggests that using 45 years as the screening threshold may be too high [49]. Karsenti et al. initially assessed ADR and High-Risk ADR using 5-year age intervals. Out of 6027 colonoscopies, the overall ADR was 28.6%, surpassing our 20.5% (24.8% when including patients over 54 years old), with a similar rate in individuals under 45 years (16.9% vs. 15.9%). Our total ADR corresponded to the findings of this extensive cohort study (22-23.6%) [14].

Conclusively, neither the ADR nor the PDR exhibited significant differences between the age groups of 45–49 and 50–55. Our results strongly support commencing CRC screenings at the age of 45.

Recent modeling studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of initiating colorectal cancer screening at age 45, emphasizing the influence of population risk profiles, healthcare infrastructure, and adherence rates. Ladabaum et al. reported that starting screening at 45 years in the U.S. is cost-effective (approximately $33,900 per QALY gained), but highlighted that optimizing adherence among older unscreened individuals may yield greater benefits at lower costs [50]. Similarly, a study by Half et al. in Israel demonstrated that while initiating screening at 45 is clinically beneficial, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio varies significantly (23,800–53,900 NIS/QALY for FIT, and 110,600–162,700 NIS/QALY for colonoscopy), underlining the importance of resource allocation strategies [51]. In Germany, Lwin et al.. showed that colonoscopy-based screening from age 45 can be cost-effective (€1,029–9,763 per QALY gained), but the model outcomes were highly sensitive to screening adherence rates and healthcare system capacities [50]. These findings collectively suggest that while our observed high PDR in the 45–49 age group supports the clinical rationale for earlier screening, careful consideration of resource burden and cost-effectiveness is crucial when formulating screening policies.

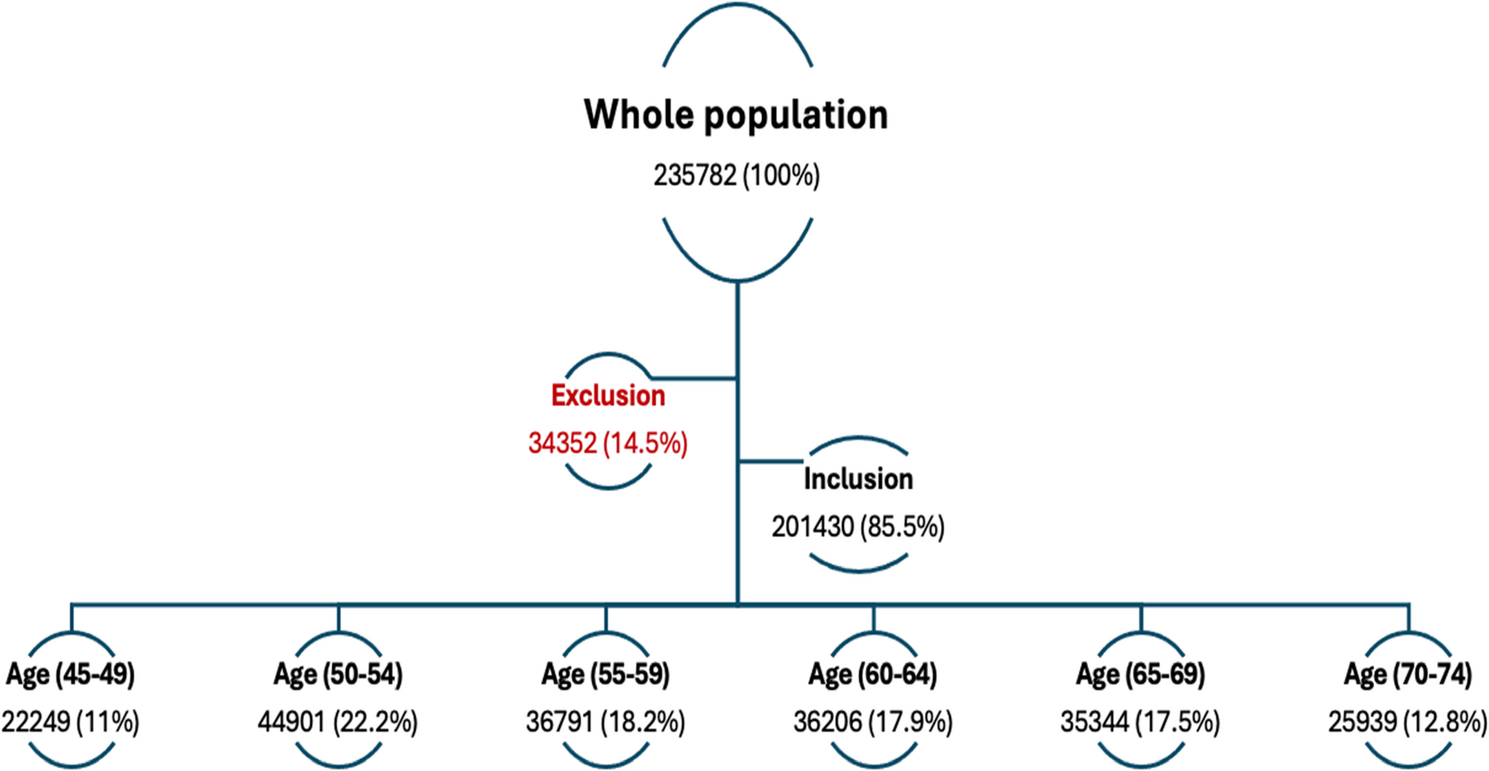

Finally, we fully acknowledge that this study is based on data from a single healthcare network (Assuta Medical Centers) in Israel, and that the findings may reflect characteristics unique to the Israeli population and healthcare system. Israel’s population is notably diverse, encompassing individuals of European, Middle Eastern, and North African descent, among other backgrounds. The retrospective design utilized real-world data from a large-volume healthcare network, where colonoscopy was performed either through self-referral or physician-directed referral. Consequently, there is potential for selection bias, particularly within the 45–49 age group, which may represent a more health-conscious subset or have been referred based on subtle clinical cues that are not explicitly recorded. To mitigate this, we applied rigorous exclusion criteria aimed at approximating an average-risk screening cohort, excluding individuals with a family history of CRC or polyps, prior neoplastic findings, inflammatory bowel disease, gastrointestinal symptoms, or inadequate bowel preparation. This approach is aligned with international CRC screening guidelines and strengthens the internal validity of ADR and PDR comparisons across age groups. Nevertheless, residual referral-related bias may remain, and the findings may not fully represent outcomes expected in an organized, population-based screening program, where individuals are systematically invited for their initial screening at age 45.

Moreover, the study did not capture long-term clinical outcomes such as CRC incidence, progression, or mortality. Adenomas were not stratified by size, histologic subtype, or dysplasia grade, which limited the ability to distinguish between advanced and non-advanced lesions. Additional influential variables such as lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol use, obesity, physical inactivity) and comorbidities were also unavailable in the dataset. Although such limitations are common in large retrospective studies, they limit our ability to account for confounding variables fully. Finally, this analysis focused exclusively on detection outcomes and did not assess procedure-related complications, such as bleeding or perforation.

A potential limitation of our study is the inability to fully verify that all included patients were true average-risk screening candidates. Some cases may have involved diagnostic or surveillance colonoscopies. While we attempted to review referral information to minimize misclassification, this limitation should be taken into account when interpreting our findings. Another limitation of this study is the absence of ethnicity-based analysis. Due to inconsistently recorded ethnicity data in our cohort, we were unable to explore potential disparities in screening outcomes among Israel’s diverse population. Future studies with systematically collected demographic data are needed to address this important question.

While colonoscopy remains highly effective for CRC screening, it carries inherent risks, including bleeding, perforation, and sedation-related complications, with serious adverse events reported in approximately 2–5 per 1,000 procedures. As the screening age is lowered and the number of procedures increases, careful attention must be paid to balancing the benefits of early detection with the potential harms associated with the procedure. Quality indicators such as withdrawal time, bowel preparation adequacy, and endoscopist experience play crucial roles in minimizing these risks. Although our study did not capture complication data, these safety considerations must be integrated into screening policy decisions.