Adding a MET gene inhibitor enhances the effect of combined chemotherapy and immunotherapy when treating patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC), according to authors of a multicenter study published in Cell Reports Medicine. These findings provide strong preclinical and translational evidence supporting MET inhibition as a therapeutic approach to overcome treatment resistance in patients with SCLC.1

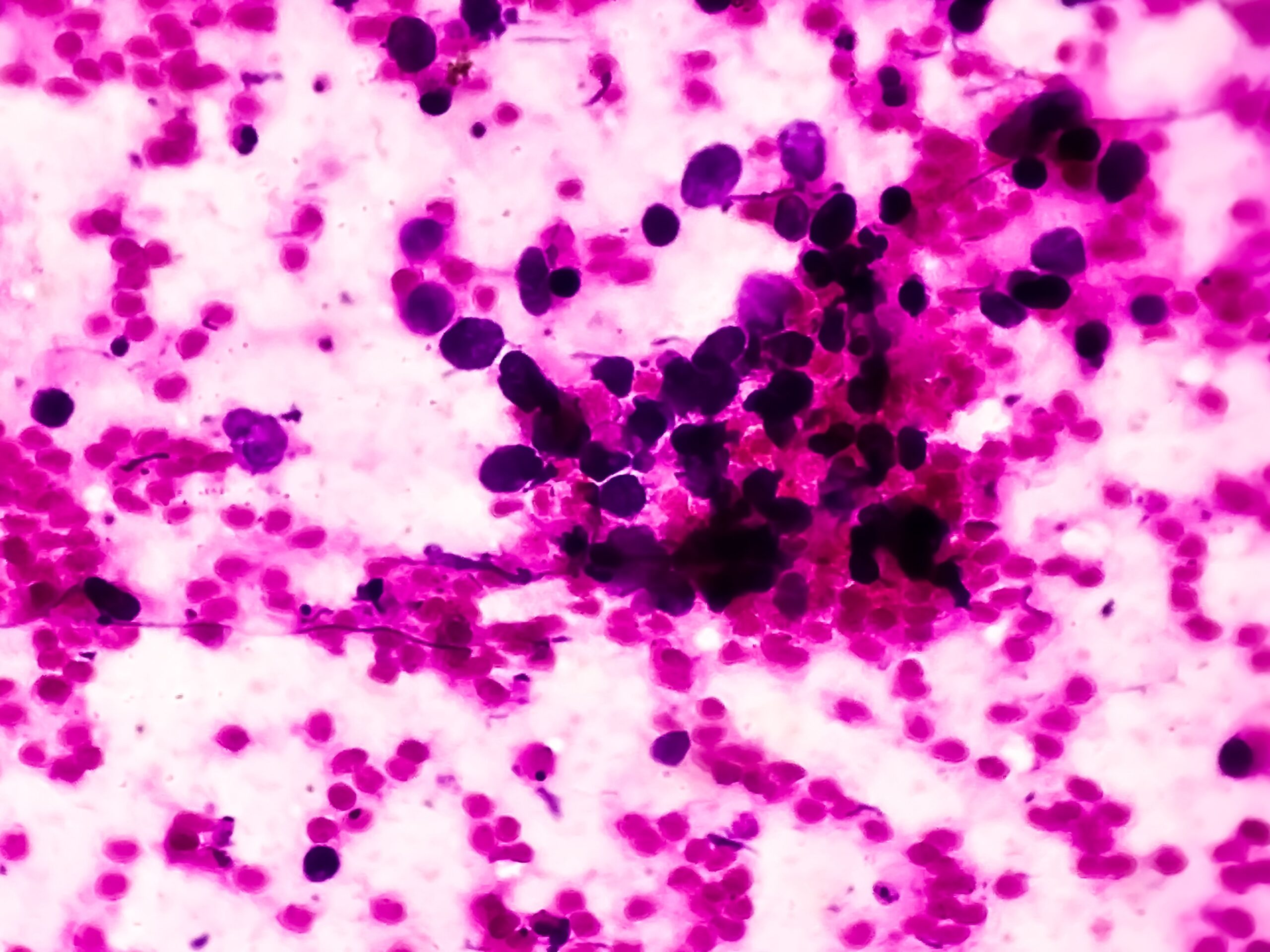

Image credit: Arif Biswas | stock.adobe.com

SCLC accounts for about 15% of all lung cancer cases, according to the authors, and despite recent advancements, prognosis remains poor. Currently, it is recommended that patients with SCLC receive a combination of anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies with platinum and etoposide, which offers a 2 to 3 median overall survival (approximately 12-13 months) over chemotherapy alone. Only 17.6% are estimated to achieve long-term benefit.1

Further, the activation of the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) receptor (MET)/HGF signaling pathway induces chemoresistance in SCLC through epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Of note, pharmacological MET inhibition was able to revert EMT and resensitize SCLC tumors to chemotherapy. In cancer, the dysregulation of the MET/HGF pathway in immune cells can induce immunoregulatory and tolerogenic phenotypes, leading to an immunosuppressive microenvironment that expedites immune evasion and tumor growth. For these reasons, the investigators assessed whether MET inhibition may enhance antitumor immune responses in SCLC when added to standard chemoimmunotherapy.1

Preclinical studies that utilized SCLC models show that combining savolitinib (Orpathys; AstraZeneca)—a MET inhibitor—with anti-PD-L1 antibodies, and in some cases chemotherapy, significantly enhanced antitumor effects and survival compared with standard therapies alone. These benefits were linked to modulation of the tumor microenvironment, including reduced immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells and an increased infiltration of cytotoxic T cells. Similarly, other tumor types (eg, melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma) reinforce the immunomodulatory role of MET inhibition as a complement to checkpoint blockade, supporting its potential as a dual-targeted strategy.1

Of note, in human SCLC samples, tumor-associated macrophages were more prevalent than tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes—particularly in the SCLC-P subtype—and were associated with poorer responses to immunotherapy, highlighting their role as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets. RNA sequencing further showed variability in immune cell populations, suggesting that specific immune signatures may better predict immunotherapy response than overall infiltration. Additionally, circulating HGF levels correlated with tumor burden, mesenchymal phenotype, and potential resistance to therapy, emphasizing the relevance of MET activation in treatment resistance. Importantly, combining MET inhibitors with chemoimmunotherapy demonstrated tolerable toxicity in both preclinical and clinical settings, supporting further evaluation of this strategy in clinical trials for SCLC patients.1

“We observed that combining immunotherapy and chemotherapy with a MET inhibitor makes immunotherapy more effective, increasing both survival and tumor response in mouse models,” lead author Edurne Arriola, MD, researcher in the Cancer Molecular Therapy Research Group and head of the Lung Cancer Section at the Hospital del Mar Medical Oncology Department, said in a news release. “This study represents the culmination of more than 10 years of research.”2

The authors acknowledged that the study had some limitations. Although MET pathway activation in tumors can promote tumor resistance in SCLC, this activation is known to be heterogeneous both within and between tumors. Additionally, mouse SCLC models that exhibit low to undetectable MET protein expression in the tumor cells were utilized, while MET is expressed in myeloid cell populations. For this reason, the ability to fully evaluate the impact of MET inhibition in a setting of active MET signaling in SCLC tumor cells was limited. Some of the results did not achieve statistical significance because of the high variability in responses. Regardless, the authors said that consistent results have been observed favoring the combination strategies, which support their findings. There was also a limited number of patient samples for biomarker studies, and further research could better address this limitation.1

“This strategy slowed tumor growth and, in some cases, completely suppressed it. When we analyzed survival and tumor progression, mice treated with the MET inhibitor had better survival outcomes,” Arriola explained. “[When MET is inhibited,] the tumor microenvironment—which contributes to treatment resistance—changes, making it easier for immune system T cells, activated by immunotherapy, to act.”2