Surgical specialization training has evolved considerably in recent years [21]. Especially during the Covid-19 period, the number of assisted surgeries decreased along with the total number of surgeries performed by residents continuing their training, leading to gaps in resident education [22,23,24]. Recently, surgical training has become more challenging due to the rise in resident numbers and the decline in available educators. For these reasons, the use of surgical videos in training has increased more frequently. Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate these videos, which serve as educational tools, objectively. Additionally, analyzing parameters such as the number of views, likes, and the length of these videos by correlating them with IVORY and LAP-VEGaS scores can provide insights for creating new videos. In our study, we found that the quality of endoscopic type 1 tympanoplasty and myringoplasty surgery videos uploaded to YouTube was generally low in terms of education. Previous studies assessing the quality of surgical videos in otolaryngology often used grading systems that were not specific to the field. These studies typically employed general quality scales like JAMA, DISCERN, or the Global Quality Score (GQS) [25,26,27]. Recently, some studies have evaluated otologic surgical videos using the IVORY grading system for procedures such as DSR, stapedectomy, and parotidectomy [1, 2, 18]. A common finding across these studies is that the videos assessed did not meet the expected educational quality standards. Similarly, in our study, the majority of the evaluated videos were scored as low-quality according to the IVORY scale.

In Mayer et al.‘s study, a correlation was found between the number of views and the total IVORY score videos [18]. However, in Yıldırım and Özdilek’s study, no such correlation was found [2]. In our study, the number of views was not significantly correlated with the IVORY score (p = 0.940), but there was a significant positive correlation between the number of views and the LAP-VEGaS score. (r = 0.299, p < 0.002).

In our analysis, we found that increasing video length had a negative impact on the IVORY score in Section B (technical aspects). This section includes questions that assess the video based on its duration, so longer videos are expected to have lower scores in Section B. Conversely, scores for Section D (surgical procedure) increased significantly with video length, likely because longer videos allowed for more detailed descriptions of the surgical process. However, the total IVORY score was negatively affected by longer video length in the correlation analysis, suggesting that the extended duration of some videos may not have been used effectively. In contrast, video duration was not identified as a significant predictor in the regression model, which may indicate the influence of potential interactions or the effect of other confounding variables.

Videos with a higher number of likes performed better in Sections B and D of the IVORY score, suggesting that providing technical details and thoroughly explaining the surgical procedure may enhance a video’s appeal. Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was observed between the number of likes and LAP-VEGaS scores, indicating that higher-quality videos tend to receive more viewer approval. This relationship was also confirmed in the linear regression model, where the number of likes emerged as a significant positive predictor of LAP-VEGaS scores (B = 0.008, p = 0.002), reinforcing the association between perceived video quality and viewer engagement.

A significant negative correlation was found between dislikes and Section E, indicating that videos lacking critical organ-specific components (such as the demonstration of essential steps in the surgical procedure) were more likely to attract dislikes. The like rate was positively correlated with Section E, meaning that videos with well-executed organ-specific sections were associated with higher like rates and fewer dislikes.

Older videos generally received lower quality scores, and this trend was supported by both correlation and regression analyses. In our study, the video upload date was significantly negatively associated with both IVORY and LAP-VEGaS scores (p < 0.001). Linear regression analyses further confirmed this relationship: video upload time was a significant negative predictor for both LAP-VEGaS (B = − 0.001, p < 0.001) and IVORY (B = − 0.001, p < 0.001) scores. These findings suggest that older videos may have lower technical and pedagogical quality, possibly due to limitations in recording equipment, editing capabilities, and the absence of standardized educational video guidelines at the time they were made. Interestingly, this pattern had not been consistently observed in previous IVORY-based studies, highlighting the potential impact of changing multimedia standards on perceived educational quality [1, 2, 18].

Inter-rater reliability is essential when assessing scoring systems such as IVORY and LAP-VEGaS, especially in studies involving subjective evaluations. In our research, Cohen’s Kappa values showed good agreement for items 6, 7, and 9 of the LAP-VEGaS score, while the other items demonstrated excellent agreement. For the IVORY score, item 6 had good agreement, item 14 showed moderate agreement, and all remaining items showed excellent agreement. The variability observed in Item 14 could result from differences in how raters interpreted and segmented the videos into distinct surgical steps, which may reflect the subjective nature of the scoring criteria. Overall, both scoring systems demonstrated high inter-rater reliability, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) above 0.75. These results align with previous studies using similar video assessment tools, which have reported acceptable reliability levels when raters are properly trained and scoring criteria are well-defined [24, 28].

A review of the literature on YouTube and otolaryngology reveals that the focus has primarily been on evaluating patient informational videos [29,30,31]. The evaluation of surgical training videos has only recently gained attention [1, 2, 18, 28, 32]. While research on surgical education videos is fairly common in urology and general surgery, there have been fewer studies in otolaryngology.

In our study, the IVORY scoring system was modified to better suit the context of YouTube-based educational videos and the specific features of endoscopic type 1 tympanoplasty and myringoplasty procedures. For example, organ-specific criteria were adjusted to emphasize key video quality elements relevant to these surgical techniques. Similar modifications have been made in previous studies evaluating videos from various surgical fields [1, 2, 18]. Although such adjustments may reduce direct comparability with research using the original IVORY framework, they enhance the relevance and usefulness of the scoring criteria for our particular procedure. This customized approach allowed for a more detailed and context-aware assessment of video quality.

While this study primarily centered on objectively assessing video quality, it is also crucial to consider the broader context of content creation and user behavior on platforms like YouTube. Although content creators do not disclose their specific motivations for uploading surgical videos, it can be assumed that the videos—many of which are excerpts from live surgeries—mainly target an audience of otolaryngology residents and specialist physicians rather than patients seeking general information. These videos may serve various purposes, such as educational uses, showcasing surgical techniques, or generating income or visibility through video content. Regardless of the original intent, such videos can still offer educational value by demonstrating surgical techniques, anatomical landmarks, the use of new surgical instruments, procedural tips, or aspects of training that may have been insufficiently covered during residency. In a survey of 70 surgical residents, medical students, and faculty surgeons, 95% of participants reported regularly watching surgical videos before performing surgeries, with YouTube being the most popular platform. YouTube’s widespread accessibility—available as a mobile app on nearly all smartphones, free of charge, and open to global content upload and viewing—likely explains its popularity among surgeons as an on-demand educational resource [33].

Within the framework of widely accepted educational theories such as Bloom’s taxonomy and Miller’s pyramid of clinical competence, watching high-quality surgical videos can support lower-level cognitive objectives, including knowledge acquisition, comprehension, and recognition of procedural steps. Visually well-designed, structured, and pedagogically aligned videos help develop mental models, especially for learners in the early stages of surgical training [34,35,36]. The LAP-VEGaS and IVORY video assessment systems are valuable tools for evaluating the presentation quality of such materials and generally align with approaches like Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. For instance, items related to the structured presentation of surgical steps and use of visual aids reflect Mayer’s segmenting and signaling principles, which facilitate learner attention and retention. Similarly, videos with minimal extraneous content and clear narration adhere to the coherence principle, reducing cognitive overload. However, these systems seem to fall short in capturing more comprehensive pedagogical dimensions, such as clearly defined learning outcomes, assessment of learners’ cognitive engagement, and measurement of educational effectiveness. Therefore, we believe that to more holistically define and evaluate educational quality, these scoring systems should be more closely integrated with advanced learning theories. Future scoring frameworks may benefit from incorporating validated educational metrics that align with broader instructional design and multimedia learning principles.

In European countries, otolaryngology residency training is based on the core curricula and logbooks outlined by the UEMS ORL Section and Board training requirements [37]. Currently, these programs do not include educational objectives related to using videos as instructional materials, nor do they cover training in video assessment, editing, or production. However, every resident is also a potential peer educator and future trainer. Active participation in the learning process is essential for reaching higher cognitive levels of learning. Activities like producing, editing, and narrating educational videos can foster deeper understanding by encouraging learners to synthesize and organize knowledge while taking on a teaching role. Familiarity with video assessment criteria is also helpful for creating new, high-quality content. Supervised video creation integrated into surgical education curricula may effectively bridge passive observation and active development of clinical skills. We believe future research should examine the role and impact of such video-based instructional strategies within structured training programs.

This study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to evaluate the quality of endoscopic type 1 tympanoplasty and myringoplasty videos. Previous studies have generally focused on total IVORY scores, with little attention to section-specific analysis. We believe that analyzing videos segment by segment is essential, as viewer behaviors, view rates, likes, dislikes, and comments have been linked to specific parts of the videos. By focusing on these sections, video creators can potentially reach a larger audience and enhance video quality. We also recommend developing and widely adopting a specialized grading system for otolaryngology, instead of relying solely on general video scoring systems.

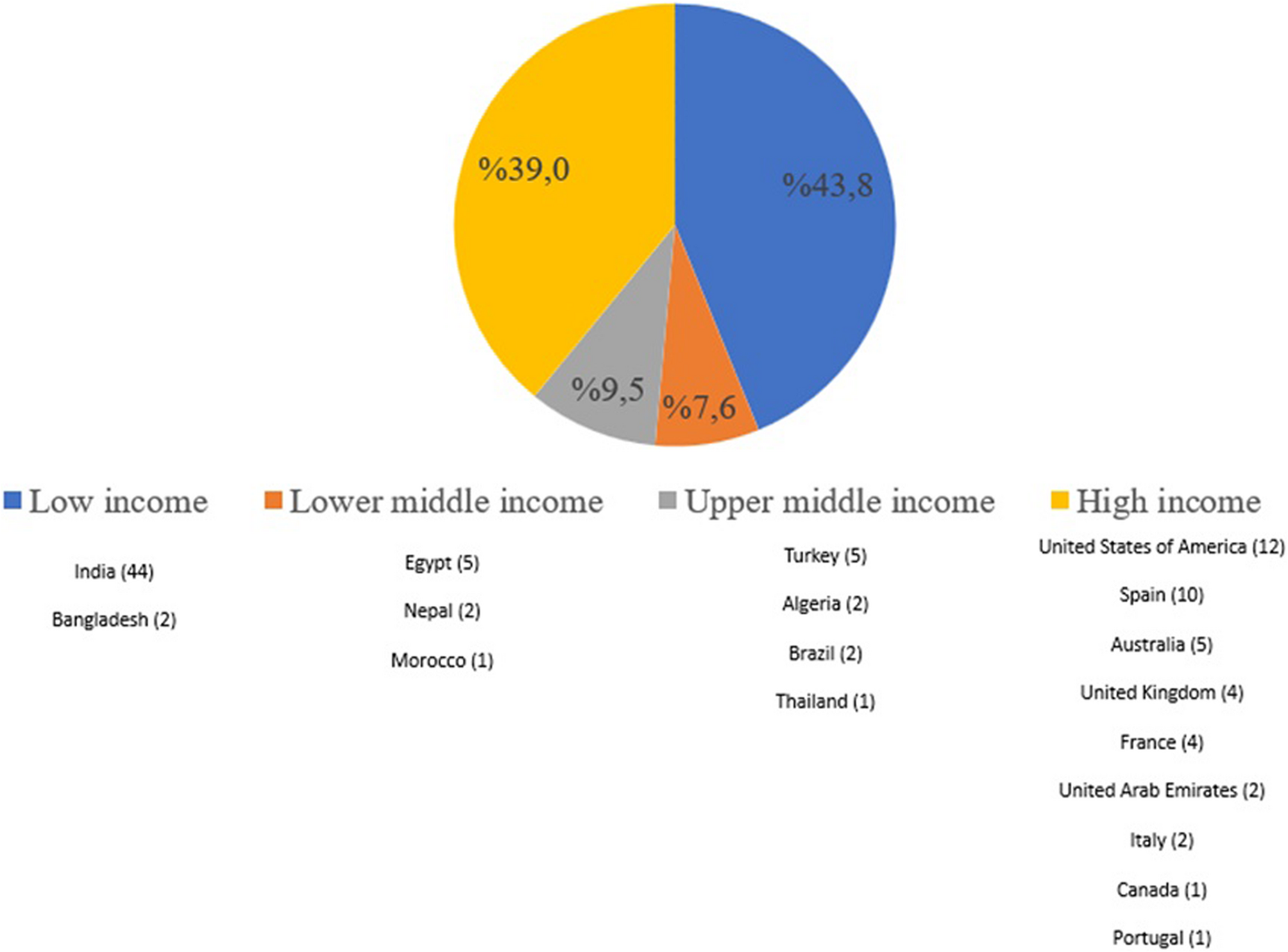

There are some limitations to our study. One limitation is that videos were selected solely based on their English language and a minimum view count. While these criteria were chosen to ensure accessibility, relevance, and comparability of content, they may have introduced selection bias by excluding potentially high-quality videos in other languages or with limited exposure. Using only English content may especially underrepresent surgical techniques from non-English-speaking countries. Similarly, restricting inclusion to videos with over 1.000 views might exclude recently uploaded or niche instructional videos that have not yet gained widespread visibility. Our research focused only on videos from a single platform (YouTube), and other platforms were not considered. Although YouTube offers broad accessibility and convenience for learners, it also has inherent limitations as an educational platform. Content on YouTube is not peer- reviewed, and the qualifications of content creators are often not disclosed, raising concerns about the accuracy, safety, and educational quality of surgical videos. YouTube’s engagement-based algorithm tends to favor videos with high watch time or user interaction, metrics that do not necessarily reflect educational value. As a result, newly uploaded yet high-quality videos, especially those made by academic institutions or experienced educators, may be overshadowed by more popular but less pedagogically sound content. While all analyzed videos were recorded during surgeries, they are likely to be clicked, liked, and commented on by viewers who are not necessarily healthcare professionals. This cycle, where popularity is driven by engagement rather than instructional merit, may limit learners’ access to the most relevant and well-prepared material. We did not formally assess or verify the credentials of video uploaders. It is plausible that content uploaded by experienced surgeons or academic institutions may differ in quality from that shared by non-experts or laypersons. Additionally, the motivations behind uploading these videos may not always be educational. As Luu et al. noted, the likelihood of uploaders knowing the IVORY and LAP-VEGaS guidelines is quite low [24]. Video uploaders were evaluated based on criteria they probably did not consider when creating their content. Another limitation is the lack of external validation for the modified IVORY scoring system. While modifications were tailored to better reflect the characteristics of endoscopic tympanoplasty and myringoplasty videos on YouTube, the newly added or omitted items have not yet undergone independent validation. Future studies should aim to assess the construct validity, reliability, and applicability of these modifications across different datasets and surgical procedures, while also expanding to multilingual content and exploring other platforms or institutional video libraries to gain a more comprehensive understanding.